10

10

0

On January 1, 1758, the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature established the "starting point" for standardized species names across the animal kingdom, based on the binomial nomenclature by Carolus Linnaeus 10th edition of Systema Naturae. From the article:

"Taxonomy - The Linnaean system

Carolus Linnaeus, who is usually regarded as the founder of modern taxonomy and whose books are considered the beginning of modern botanical and zoological nomenclature, drew up rules for assigning names to plants and animals and was the first to use binomial nomenclature consistently (1758). Although he introduced the standard hierarchy of class, order, genus, and species, his main success in his own day was providing workable keys, making it possible to identify plants and animals from his books. For plants he made use of the hitherto neglected smaller parts of the flower.From

Linnaeus attempted a natural classification but did not get far. His concept of a natural classification was Aristotelian; i.e., it was based on Aristotle’s idea of the essential features of living things and on his logic. He was less accurate than Aristotle in his classification of animals, breaking them up into mammals, birds, reptiles, fishes, insects, and worms. The first four, as he defined them, are obvious groups and generally recognized; the last two incorporate about seven of Aristotle’s groups.

The standard Aristotelian definition of a form was by genus and differentia. The genus defined the general kind of thing being described, and the differentia gave its special character. A genus, for example, might be “Bird” and the species “Feeding in water,” or the genus might be “Animal” and the species “Bird.” The two together made up the definition, which could be used as a name. Unfortunately, when many species of a genus became known, the differentia became longer and longer. In some of his books Linnaeus printed in the margin a catch name, the name of the genus and one word from the differentia or from some former name. In this way he created the binomial, or binary, nomenclature. Thus, modern humans are Homo sapiens, Neanderthals are Homo neanderthalensis, the gorilla is Gorilla gorilla, and so on.

Classification since Linnaeus

Classification since Linnaeus has incorporated newly discovered information and more closely approaches a natural system. When the life history of barnacles was discovered, for example, they could no longer be associated with mollusks because it became clear that they were arthropods (jointed-legged animals such as crabs and insects). Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, an excellent taxonomist despite his misconceptions about evolution, first separated spiders and crustaceans from insects as separate classes. He also introduced the distinction, no longer accepted by all workers as wholly valid, between vertebrates—i.e., those with backbones, such as fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals—and invertebrates, which have no backbones. The invertebrates, defined by a feature they lack rather than by the features they have, constitute in fact about 90 percent of the diversity of all animals. The mixed group “Infusoria,” which included all the microscopic forms that would appear when hay was let stand in water, was broken up into empirically recognized groups by the French biologist Felix Dujardin. The German biologist Ernst Haeckel proposed the term Protista in 1866 to include chiefly the unicellular plants and animals because he realized that, at the one-celled level, there could no longer be a clear distinction

The process of clarifying relationships continues. Only in 1898 were agents of disease discovered (viruses) that would pass through the finest filters, and it was not until 1935 that the first completely purified virus was obtained. Primitive spore-bearing land plants (Psilophyta) from the Cambrian Period, which dates from 541 million to 485 million years ago, were discovered in Canada in 1859. The German botanist Wilhelm Hofmeister in 1851 gave the first good account of the alternation of generations in various nonflowering (cryptogamous) plants, on which many major divisions of higher plants are based. The phylum Pogonophora (beardworms) was recognized only in the 20th century.

The immediate impact of Darwinian evolution on classification was negligible for many groups of organisms and unfortunate for others. As taxonomists began to accept evolution, they recognized that what had been described as natural affinity—i.e., the more or less close similarity of forms with many of the same characters—could be explained as relationship by evolutionary descent. In groups with little or no fossil record, a change in interpretation rather than alteration of classifications was the result. Unfortunately, some authorities, believing that they could derive the group from some evolutionary principle, would proceed to reclassify it. The classification of earthworms and their allies (Oligochaeta), for example, which had been studied by using the most complex organism easily obtainable and by then arranging progressively simple forms below it, was changed after the theory of evolution appeared. The simplest oligochaete, the tiny freshwater worm Aeolosoma, was considered to be most primitive, and classifiers arranged progressively complex forms above it. Later, when it was realized that Aeolosoma might well have been secondarily simplified (i.e., evolved from a more complex form), the tendency was to start in the middle of the series and work in both directions. Biased names for the major subgroups (Archioligochaeta, Neoligochaeta) were widely accepted when in fact there was no evidence for the actual course of evolution of this and other animal groups. Groups with good fossil records suffered less from this type of reclassification because good fossil material allowed the placing of forms according to natural affinities; knowledge of the strata in which they were found allowed the formulation of a phylogenetic tree (i.e., one based on evolutionary relationships), or dendrite (also called a dendrogram), irrespective of theory (see also phylogeny).

The long-term impact of Darwinian evolution has been different and very important. It indicates that the basic arrangement of living things, if enough information were available, would be a phylogenetic tree rather than a set of discrete classes. Many groups are so poorly known, however, that the arrangement of organisms into a dendrite is impossible. Extensive and detailed fossil sequences—the laying out of actual specimens—must be broken up arbitrarily. Many groups, especially at the species level, show great geographical variation, so that a simple definition of species is impossible. Difficulties of classification at the species level are considerable. Many plants show reticulate (chain) evolution, in which species form and then subsequently hybridize, resulting in the formation of new species. And because many plants and animals have abandoned sexual reproduction, the usual criteria for the species—interbreeding within a pool of individuals—cannot be applied. Nothing about the viruses, moreover, seems to correspond to the species of higher organisms.

The objectives of biological classification

A classification or arrangement of any sort cannot be handled without reference to the purpose or purposes for which it is being made. An arrangement based on everything known about a particular class of objects is likely to be the most useful for many particular purposes. One in which objects are grouped according to easily observed and described characteristics allows easy identification of the objects. If the purpose of a classification is to provide information unknown to or not remembered by the user but relating to something the name of which is known, an alphabetical arrangement may be best. Specialists may want a classification relating only to one aspect of a subject. A chemist analyzing the essential oils of plants, for instance, is interested only in the oil content of plants and probably requires such information in far greater detail than would anyone else.

Classification is used in biology for two totally different purposes, often in combination, namely, identifying and making natural groups. The specimen or a group of similar specimens must be compared with descriptions of what is already known. This type of classification, called a key, provides as briefly and as reliably as possible the most obvious characteristics useful in identification. Very often they are set out as a dichotomous key with opposing pairs of characters. The butterflies of a region, for example, might first be separated into those with a lot of white on the wings and those with very little; then each group could be subdivided on the basis of other characters. One disadvantage of such classifications, which are useful for well-known groups, is that a mistake may produce a ridiculous answer, since the groups under each division need have nothing in common but the chosen character (e.g., white on the butterfly wings). In addition, if the group being keyed is large or given to great variation, the key may be extremely complex and may rely on characters difficult to evaluate. Moreover, if the form in question is a new one or one that is not in the key (being, perhaps, unrecorded from the region to which the key applies), it may be identified incorrectly. Many unrelated butterflies have a lot of white on the wings—a few swallowtails, the well-known cabbage whites, some of the South American dismorphiines, and a few satyrids. Should identification of an undescribed form of fritillary butterfly containing much white on the wings be desired, the use of a key could result in an incorrect identification of the butterfly. In order to avoid such mistakes, it is necessary to consider many characters of the organism—not merely one aspect of the wings but their anatomy and the features of the various stages in the life cycle.

Unfortunately, little is known about many of the vast variety of living things. In poorly known groups—and most living things are poorly known—the first objective is identification. There are, for example, about 250,000 species of beetles, and many are known only from a single specimen of the adult. In such groups the tendency is to produce classifications which, though purporting to be natural ones, are actually dichotomous keys. Although most common earthworms have on each body segment four pairs of special bristles (chaetae) that are used in locomotion, some species have many chaetae arranged in a complete ring around the body on each segment (perichaetine condition). Because the chaetae are an easily observed character, the latter species were once placed together as a natural group, the family Perichaetidae. Knowledge of other aspects of earthworm anatomy, however, made it obvious that several different groups had independently evolved the perichaetine condition. Many current so-called natural groups, especially those at the lower levels of classification, are probably not natural at all but are based on some easily observed characters.

A natural classification is advantageous in that it groups together forms that seem fundamentally to be related. Information utilized in the definition of a group thus need not be repeated for each constituent. This provides concision and efficient information storage. A certain amount of prediction is also possible—a new form with a few ascertained characters similar to those of a natural group probably has other similar characters. As long as no difficult intermediary forms are found, all of the different types can be classified into definite discrete categories. Biological classification has progressed from artificial or key classifications to a natural classification. It has also been realized that division into sharply separated groups often is not possible. Formal classification thus sometimes obscures actual relationships.

The taxonomic process

Basically, no special theory lies behind modern taxonomic methods. In effect, taxonomic methods depend on: (1) obtaining a suitable specimen (collecting, preserving and, when necessary, making special preparations); (2) comparing the specimen with the known range of variation of living things; (3) correctly identifying the specimen if it has been described, or preparing a description showing similarities to and differences from known forms, or, if the specimen is new, naming it according to internationally recognized codes of nomenclature; (4) determining the best position for the specimen in existing classifications and determining what revision the classification may require as a consequence of the new discovery; and (5) using available evidence to suggest the course of the specimen’s evolution. Prerequisite to these activities is a recognized system of ranks in classifying, recognized rules for nomenclature, and a procedure for verification, irrespective of the group being examined. A group of related organisms to which a taxonomic name is given is called a taxon (plural taxa).

Ranks

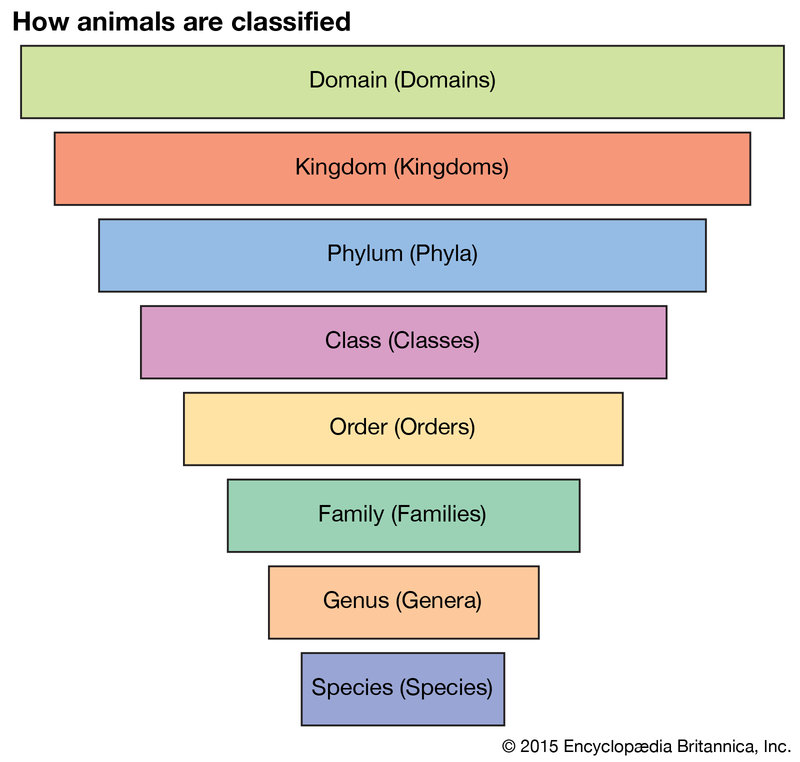

The goal of classifying is to place an organism into an already existing group or to create a new group for it, based on its resemblances to and differences from known forms. To this end, a hierarchy of categories is recognized.

For example, an ordinary flowering plant, on the basis of gross structure, is clearly one of the higher green plants—not a fungus, bacterium, or animal—and it can easily be placed in the kingdom Plantae (or Metaphyta). If the body of the plant has distinct leaves, roots, a stem, and flowers, it is placed with the other true flowering plants in the division Magnoliophyta (or Angiospermae), one subcategory of the Plantae. If it is a lily, with swordlike leaves, with the parts of the flowers in multiples of three, and with one cotyledon (the incipient leaf) in the embryo, it belongs with other lilies, tulips, palms, orchids, grasses, and sedges in a subgroup of the Magnoliophyta, which is called the class Liliatae (or Monocotyledones). In this class it is placed, rather than with orchids or grasses, in a subgroup of the Liliatae, the order Liliales.

This procedure is continued to the species level. Should the plant be different from any lily yet known, a new species is named, as well as higher taxa, if necessary. If the plant is a new species within a well-known genus, a new species name is simply added to the appropriate genus. If the plant is very different from any known monocot, it might require, even if only a single new species, the naming of a new genus, family, order, or higher taxon. There is no restriction on the number of forms in any particular group. The number of ranks that is recognized in a hierarchy is a matter of widely varying opinion. Shown in Table 1 are seven ranks that are accepted as obligatory by zoologists and botanists.

In botany the term division is often used as an equivalent to the term phylum of zoology. The number of ranks is expanded as necessary by using the prefixes sub-, super-, and infra- (e.g., subclass, superorder) and by adding other intermediate ranks, such as brigade, cohort, section, or tribe. Given in full, the zoological hierarchy for the timber wolf of the Canadian subarctic would be as follows:

Kingdom Animalia

Subkingdom Metazoa

Phylum Chordata

Subphylum Vertebrata

Superclass Tetrapoda

Class Mammalia

Subclass Theria

Infraclass Eutheria

Cohort Ferungulata

Superorder Ferae

Order Carnivora

Suborder Fissipeda

Superfamily Canoidea

Family Canidae

Subfamily Caninae

Tribe (none described for this group)

Genus Canis

Subgenus (none described for this group)

Species Canis lupus (wolf)

Subspecies Canis lupus occidentalis (northern timber wolf)

Although the name of the species is binomial (e.g., Canis lupus) and that of the subspecies trinomial (C. lupus occidentalis for the northern timber wolf, C. lupus lupus for the northern European wolf), all other names are single words. In zoology, convention dictates that the names of superfamilies end in -oidea, and the code dictates that the names of families end in -idae, those of subfamilies in -inae, and those of tribes in -ini. Unfortunately, there are no widely accepted rules for other major divisions of living things, because each major group of animals and plants has its own taxonomic history and old names tend to be preserved. Apart from a few accepted endings, the names of groups of high rank are not standardized and must be memorized.

The discovery of a living coelacanth fish of the genus Latimeria in 1938 caused virtually no disturbance of the accepted classification, since the suborder Coelacanthi was already well known from fossils. When certain unusual worms were discovered in the depths of the oceans about 10 years later, however, it was necessary to create a new phylum, Pogonophora, for them since they showed no close affinities to any other known animals. The phylum Pogonophora, as usually classified, has one class—the animals in the phylum are relatively similar—but there are two orders, several families and genera, and more than 100 species. Both of these examples have been widely accepted by authorities in their respective areas of taxonomy and may be considered stable taxa.

It cannot be too strongly emphasized that there are no explicit taxonomic characters that define a phylum, class, order, or other rank. A feature characteristic of one phylum may vary in another phylum among closely related members of a class, order, or some lower group. The complex carbohydrate cellulose is characteristic of two kingdoms of plants, but among animals cellulose occurs only in one subphylum of one phylum. It would simplify the work of the taxonomist if characters diagnostic of phylum rank in animals were always taken from one feature, the skeleton, for example; those of class rank, from the respiratory organs; and so on down the taxonomic hierarchy. Such a system, however, would produce an unnatural classification.

The taxonomist must first recognize natural groups and then decide on the rank that should be assigned them. Are sea squirts, for instance, so clearly linked by the structure of the extraordinary immature form (larva) to the phylum Chordata, which includes all the vertebrates, that they should be called a subphylum, or should their extremely modified adult organization be deemed more important, with the result that sea squirts might be recognized as a separate phylum, albeit clearly related to the Chordata? At present, this sort of question has no precise answer.

Some biologists believe that “numerical taxonomy,” a system of quantifying characteristics of taxa and subjecting the results to multivariate analysis, may eventually produce quantitative measures of overall differences among groups and that agreement can be achieved so as to establish the maximal difference allowed each taxonomic level. Although such agreement may be possible, many difficulties exist. An order in one authority’s classification may be a superorder or class in another. Most of the established classifications of the better-known groups result from a general consensus among practicing taxonomists. It follows that no complete definition of a group can be made until the group itself has been recognized, after which its common (or most usual) characters can be formally stated. As further information is obtained about the group, it is subject to taxonomic revision.

Nomenclature

Communication among biologists requires a recognized nomenclature, especially for the units in most common use. The internationally accepted taxonomic nomenclature is the Linnaean system, which, although founded on Linnaeus’s rules and procedures, has been greatly modified through the years. There are separate international codes of nomenclature in botany (first published in 1901), in zoology (1906), and in microbiology (bacteria and viruses, 1948). The Linnaean binomial system is not employed for viruses. There is also a code, which was established in 1953, for the nomenclature of cultivated plants, many of which are artificially produced and are unknown in the wild.

The codes, the authority for each of which stems from a corresponding international congress, differ in various details, but all include the following elements: the naming of species by two words treated as Latin; a law of priority that the first validly published and validly binomial name for a given taxon is the correct one and that any others must become synonyms; recognition that a valid binomen can apply to only one taxon, so that a name may be used both in botany and in zoology but for only one plant taxon and one animal taxon; that if taxonomic opinion about the status of a taxon is changed, the valid name can change also; and, lastly, that the exact sense in which a name is used be determined by reference to a type. Rules are also given for the obligate categories of the hierarchy and for what constitutes valid publication of a name. Finally, recommendations are given on the process of deriving names.

Linnaeus believed that there were not more than a few thousand genera of living things, each with some clearly marked character, and that the good taxonomist could memorize them all, especially if their names were well chosen. Thus, although the naming of the species might often involve much research, the genus at least could be easily found.

At the present time, in many taxa, the species has a definite biological meaning: it is defined as a group of individuals that can breed among themselves but do not normally breed with other forms. Among microorganisms and other groups in which sexual reproduction need not occur, this criterion fails.

In botanical practice, matters more usually resemble the Linnean situation. Many sorts of chromosomal variants (individuals with different arrangements of chromosomes, or hereditary material, which prevent interbreeding) and marked ecotypes (individuals whose external form is affected by the conditions of soil, moisture, and other environmental factors), as well as other forms, that would clearly be classified as separate species by the zoologist may be lumped together unrecognized or considered subspecies by the botanist. Botanists commonly use the terms variety and form to designate genetically controlled variants within plant populations below the subspecies level.

The use of a strictly biological species definition would enormously increase rather than reduce the number of names in use in botany. A recognized species of flowering plant may consist of several “chromosomal races”—i.e., identical in external appearance but genetically incompatible and, thus, effectively separate species. Such various forms are often identifiable only by cytological examination, which requires fresh material and extensive laboratory work. Many botanists have said that there has been so little stability in the accepted nomenclature that further upheavals would be intolerable and render identification impossible for many applied botanists who may not require such refinements. To postpone recognition of such forms, however, will probably cause upheaval in the future.

Some species of birds are widespread over the archipelagos of the southwest Pacific, where nearly every island may have a form sufficiently distinct to be given some kind of taxonomic recognition. For example, 73 races are currently recognized for the golden whistler (Pachycephala pectoralis). Before the realization that species could vary geographically, each island form was named as a separate species (as many of the races of P. pectoralis actually were). It is often believed—and often it is only belief rather than fact—that all of these now genetically isolated populations arose as local differentiations of a single stock. Thus, they are now usually classed in zoological usage as subspecies of one polytypic species. The term polytypic indicates that a separate description (and type specimen) is needed for each of the distinct populations, instead of one for the entire species. The use of a trinomial designation for each subspecies (e.g., Pachycephala pectoralis bougainvillei) indicates that it is regarded as simply a local representative (in this case, on Bougainville Island in the Solomons) of a more widely distributed species. The decision on whether to consider such island forms as representatives of one species depends partly on whether, in the judgment of the taxonomist, populations from adjacent islands are sufficiently similar to allow free interbreeding.

Verification and validation by type specimens

The determination of the exact organism designated by a particular name usually requires more than the mere reading of the description or the definition of the taxon to which the name applies. New forms, which may have become known since the description was written, may differ in characteristics not originally considered, or later workers may discover, by inspection of the original material, that the original author inadvertently confused two or more forms. No description can be guaranteed to be exhaustive for all time. Validation of the use of a name requires examination of the original specimen. It must, therefore, be unambiguously designated.

At one time authors might have taken their descriptions from a series of specimens or partly (or even wholly) from other authors’ descriptions or figures, as Linnaeus often did. Much of the controversy over the validity of certain names in current use, especially those dating from the late 18th century, stems from the difficulty in determining the identity of the material used by the original authors. In modern practice, a single type specimen must be designated for a new species or subspecies name. The type should always be placed in a reliable public institution, where it can be properly cared for and made available to taxonomists. For many microorganisms, type cultures are maintained in qualified institutions. Because of the short generation time of microorganisms, however, they may actually evolve during storage.

A complex nomenclature is applied to the different sorts of type specimens. The holotype is a single specimen designated by the original describer of the form (a species or subspecies only) and available to those who want to verify the status of other specimens. When no holotype exists, as is frequently the case, a neotype is selected and so designated by someone who subsequently revises the taxon, and the neotype occupies a position equivalent to that of the holotype. The first type validly designated has priority over all other type specimens. Paratypes are specimens used, along with the holotype, in the original designation of a new form; they must be part of the same series (i.e., collected at the same immediate locality and at the same time) as the holotype.

For a taxon above the species level, the type is a taxon of the next lower rank. For a genus, for instance, it is a species. From the level of the genus to that of the superfamily there are rules regarding the formation of a group name from the name of the type group. The genus Homo (human beings) is the type genus of the family Hominidae, for example, and the code forbids its removal from the family Hominidae as long as the Hominidae is treated as a valid family and the name Homo is taxonomically valid. Whatever the remainder of its contents, the family that contains the genus Homo must be the Hominidae.

Indiscriminate collecting is of little use today, but huge areas of Earth are still poorly known biologically, at least as far as many groups are concerned, and there remain many groups for which the small number of properly collected and prepared specimens precludes any thorough taxonomic analysis. Even in well-studied groups, such as the higher vertebrates, new methods of analyzing material often necessitate special collecting. The determination of variation within species or populations may necessitate the study of more specimens than are available, even when (as is usual) the specialist can utilize material from many institutions. Usually, collecting is done to fill gaps (in geographical range, geological formations, or taxonomic categories) already brought to light by specialists reviewing the available material. The well-informed collector of living things knows where to go, what to look for, and how to spot anything especially valuable or extraordinary.

The actual techniques of collecting and preserving vary greatly from one group of organisms to another—soil protozoa, fungi, or pines are neither collected nor preserved in the same manner as birds. Some animals can be preserved only in weak alcohol, but others macerate (decompose) in it. Certain earthworms “preserved” in weak alcohol simply flow out of their own skins when lifted out. Special methods are used after long experience to preserve characters of special value in taxonomy. Some methods make specimens difficult to observe; this is especially true of material that has to be sectioned or otherwise made into preparations suitable for microscopic observation.

After taxonomic material has been collected and preserved, its value can be lost unless it is accurately and completely labelled. Only rarely is unlabelled or insufficiently labelled material of any use. The taxonomist normally must know the locality of collection of each specimen (or lot of specimens), often the habitat (e.g., type of forest, marsh, type of seawater), the date, the name of the collector, and the original field number given to the specimen or lot. To this information is added the catalog number of the collection and the sex (if not already determined in the field and if relevant). The scientific identity of the specimen, as determined by an acknowledged specialist, is usually added to the label at the museum. Also included is the name of the specialist who identified the specimen. Later revisions of the classification and additional knowledge of the organism may result in later alterations of the scientific name, but the original labels must still be kept unaltered.

Other information may also be required. For example, the males and females of some insect groups are extremely different in appearance, and males and females of the same species may have to be identified. The capture of a pair in the wild actually in copulation gives a strong (but, surprisingly, not absolute) indication that the male and female belong to the same species; the labels of each specimen (if they are separated) indicate the specimen with which it was mating."

"Taxonomy - The Linnaean system

Carolus Linnaeus, who is usually regarded as the founder of modern taxonomy and whose books are considered the beginning of modern botanical and zoological nomenclature, drew up rules for assigning names to plants and animals and was the first to use binomial nomenclature consistently (1758). Although he introduced the standard hierarchy of class, order, genus, and species, his main success in his own day was providing workable keys, making it possible to identify plants and animals from his books. For plants he made use of the hitherto neglected smaller parts of the flower.From

Linnaeus attempted a natural classification but did not get far. His concept of a natural classification was Aristotelian; i.e., it was based on Aristotle’s idea of the essential features of living things and on his logic. He was less accurate than Aristotle in his classification of animals, breaking them up into mammals, birds, reptiles, fishes, insects, and worms. The first four, as he defined them, are obvious groups and generally recognized; the last two incorporate about seven of Aristotle’s groups.

The standard Aristotelian definition of a form was by genus and differentia. The genus defined the general kind of thing being described, and the differentia gave its special character. A genus, for example, might be “Bird” and the species “Feeding in water,” or the genus might be “Animal” and the species “Bird.” The two together made up the definition, which could be used as a name. Unfortunately, when many species of a genus became known, the differentia became longer and longer. In some of his books Linnaeus printed in the margin a catch name, the name of the genus and one word from the differentia or from some former name. In this way he created the binomial, or binary, nomenclature. Thus, modern humans are Homo sapiens, Neanderthals are Homo neanderthalensis, the gorilla is Gorilla gorilla, and so on.

Classification since Linnaeus

Classification since Linnaeus has incorporated newly discovered information and more closely approaches a natural system. When the life history of barnacles was discovered, for example, they could no longer be associated with mollusks because it became clear that they were arthropods (jointed-legged animals such as crabs and insects). Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, an excellent taxonomist despite his misconceptions about evolution, first separated spiders and crustaceans from insects as separate classes. He also introduced the distinction, no longer accepted by all workers as wholly valid, between vertebrates—i.e., those with backbones, such as fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals—and invertebrates, which have no backbones. The invertebrates, defined by a feature they lack rather than by the features they have, constitute in fact about 90 percent of the diversity of all animals. The mixed group “Infusoria,” which included all the microscopic forms that would appear when hay was let stand in water, was broken up into empirically recognized groups by the French biologist Felix Dujardin. The German biologist Ernst Haeckel proposed the term Protista in 1866 to include chiefly the unicellular plants and animals because he realized that, at the one-celled level, there could no longer be a clear distinction

The process of clarifying relationships continues. Only in 1898 were agents of disease discovered (viruses) that would pass through the finest filters, and it was not until 1935 that the first completely purified virus was obtained. Primitive spore-bearing land plants (Psilophyta) from the Cambrian Period, which dates from 541 million to 485 million years ago, were discovered in Canada in 1859. The German botanist Wilhelm Hofmeister in 1851 gave the first good account of the alternation of generations in various nonflowering (cryptogamous) plants, on which many major divisions of higher plants are based. The phylum Pogonophora (beardworms) was recognized only in the 20th century.

The immediate impact of Darwinian evolution on classification was negligible for many groups of organisms and unfortunate for others. As taxonomists began to accept evolution, they recognized that what had been described as natural affinity—i.e., the more or less close similarity of forms with many of the same characters—could be explained as relationship by evolutionary descent. In groups with little or no fossil record, a change in interpretation rather than alteration of classifications was the result. Unfortunately, some authorities, believing that they could derive the group from some evolutionary principle, would proceed to reclassify it. The classification of earthworms and their allies (Oligochaeta), for example, which had been studied by using the most complex organism easily obtainable and by then arranging progressively simple forms below it, was changed after the theory of evolution appeared. The simplest oligochaete, the tiny freshwater worm Aeolosoma, was considered to be most primitive, and classifiers arranged progressively complex forms above it. Later, when it was realized that Aeolosoma might well have been secondarily simplified (i.e., evolved from a more complex form), the tendency was to start in the middle of the series and work in both directions. Biased names for the major subgroups (Archioligochaeta, Neoligochaeta) were widely accepted when in fact there was no evidence for the actual course of evolution of this and other animal groups. Groups with good fossil records suffered less from this type of reclassification because good fossil material allowed the placing of forms according to natural affinities; knowledge of the strata in which they were found allowed the formulation of a phylogenetic tree (i.e., one based on evolutionary relationships), or dendrite (also called a dendrogram), irrespective of theory (see also phylogeny).

The long-term impact of Darwinian evolution has been different and very important. It indicates that the basic arrangement of living things, if enough information were available, would be a phylogenetic tree rather than a set of discrete classes. Many groups are so poorly known, however, that the arrangement of organisms into a dendrite is impossible. Extensive and detailed fossil sequences—the laying out of actual specimens—must be broken up arbitrarily. Many groups, especially at the species level, show great geographical variation, so that a simple definition of species is impossible. Difficulties of classification at the species level are considerable. Many plants show reticulate (chain) evolution, in which species form and then subsequently hybridize, resulting in the formation of new species. And because many plants and animals have abandoned sexual reproduction, the usual criteria for the species—interbreeding within a pool of individuals—cannot be applied. Nothing about the viruses, moreover, seems to correspond to the species of higher organisms.

The objectives of biological classification

A classification or arrangement of any sort cannot be handled without reference to the purpose or purposes for which it is being made. An arrangement based on everything known about a particular class of objects is likely to be the most useful for many particular purposes. One in which objects are grouped according to easily observed and described characteristics allows easy identification of the objects. If the purpose of a classification is to provide information unknown to or not remembered by the user but relating to something the name of which is known, an alphabetical arrangement may be best. Specialists may want a classification relating only to one aspect of a subject. A chemist analyzing the essential oils of plants, for instance, is interested only in the oil content of plants and probably requires such information in far greater detail than would anyone else.

Classification is used in biology for two totally different purposes, often in combination, namely, identifying and making natural groups. The specimen or a group of similar specimens must be compared with descriptions of what is already known. This type of classification, called a key, provides as briefly and as reliably as possible the most obvious characteristics useful in identification. Very often they are set out as a dichotomous key with opposing pairs of characters. The butterflies of a region, for example, might first be separated into those with a lot of white on the wings and those with very little; then each group could be subdivided on the basis of other characters. One disadvantage of such classifications, which are useful for well-known groups, is that a mistake may produce a ridiculous answer, since the groups under each division need have nothing in common but the chosen character (e.g., white on the butterfly wings). In addition, if the group being keyed is large or given to great variation, the key may be extremely complex and may rely on characters difficult to evaluate. Moreover, if the form in question is a new one or one that is not in the key (being, perhaps, unrecorded from the region to which the key applies), it may be identified incorrectly. Many unrelated butterflies have a lot of white on the wings—a few swallowtails, the well-known cabbage whites, some of the South American dismorphiines, and a few satyrids. Should identification of an undescribed form of fritillary butterfly containing much white on the wings be desired, the use of a key could result in an incorrect identification of the butterfly. In order to avoid such mistakes, it is necessary to consider many characters of the organism—not merely one aspect of the wings but their anatomy and the features of the various stages in the life cycle.

Unfortunately, little is known about many of the vast variety of living things. In poorly known groups—and most living things are poorly known—the first objective is identification. There are, for example, about 250,000 species of beetles, and many are known only from a single specimen of the adult. In such groups the tendency is to produce classifications which, though purporting to be natural ones, are actually dichotomous keys. Although most common earthworms have on each body segment four pairs of special bristles (chaetae) that are used in locomotion, some species have many chaetae arranged in a complete ring around the body on each segment (perichaetine condition). Because the chaetae are an easily observed character, the latter species were once placed together as a natural group, the family Perichaetidae. Knowledge of other aspects of earthworm anatomy, however, made it obvious that several different groups had independently evolved the perichaetine condition. Many current so-called natural groups, especially those at the lower levels of classification, are probably not natural at all but are based on some easily observed characters.

A natural classification is advantageous in that it groups together forms that seem fundamentally to be related. Information utilized in the definition of a group thus need not be repeated for each constituent. This provides concision and efficient information storage. A certain amount of prediction is also possible—a new form with a few ascertained characters similar to those of a natural group probably has other similar characters. As long as no difficult intermediary forms are found, all of the different types can be classified into definite discrete categories. Biological classification has progressed from artificial or key classifications to a natural classification. It has also been realized that division into sharply separated groups often is not possible. Formal classification thus sometimes obscures actual relationships.

The taxonomic process

Basically, no special theory lies behind modern taxonomic methods. In effect, taxonomic methods depend on: (1) obtaining a suitable specimen (collecting, preserving and, when necessary, making special preparations); (2) comparing the specimen with the known range of variation of living things; (3) correctly identifying the specimen if it has been described, or preparing a description showing similarities to and differences from known forms, or, if the specimen is new, naming it according to internationally recognized codes of nomenclature; (4) determining the best position for the specimen in existing classifications and determining what revision the classification may require as a consequence of the new discovery; and (5) using available evidence to suggest the course of the specimen’s evolution. Prerequisite to these activities is a recognized system of ranks in classifying, recognized rules for nomenclature, and a procedure for verification, irrespective of the group being examined. A group of related organisms to which a taxonomic name is given is called a taxon (plural taxa).

Ranks

The goal of classifying is to place an organism into an already existing group or to create a new group for it, based on its resemblances to and differences from known forms. To this end, a hierarchy of categories is recognized.

For example, an ordinary flowering plant, on the basis of gross structure, is clearly one of the higher green plants—not a fungus, bacterium, or animal—and it can easily be placed in the kingdom Plantae (or Metaphyta). If the body of the plant has distinct leaves, roots, a stem, and flowers, it is placed with the other true flowering plants in the division Magnoliophyta (or Angiospermae), one subcategory of the Plantae. If it is a lily, with swordlike leaves, with the parts of the flowers in multiples of three, and with one cotyledon (the incipient leaf) in the embryo, it belongs with other lilies, tulips, palms, orchids, grasses, and sedges in a subgroup of the Magnoliophyta, which is called the class Liliatae (or Monocotyledones). In this class it is placed, rather than with orchids or grasses, in a subgroup of the Liliatae, the order Liliales.

This procedure is continued to the species level. Should the plant be different from any lily yet known, a new species is named, as well as higher taxa, if necessary. If the plant is a new species within a well-known genus, a new species name is simply added to the appropriate genus. If the plant is very different from any known monocot, it might require, even if only a single new species, the naming of a new genus, family, order, or higher taxon. There is no restriction on the number of forms in any particular group. The number of ranks that is recognized in a hierarchy is a matter of widely varying opinion. Shown in Table 1 are seven ranks that are accepted as obligatory by zoologists and botanists.

In botany the term division is often used as an equivalent to the term phylum of zoology. The number of ranks is expanded as necessary by using the prefixes sub-, super-, and infra- (e.g., subclass, superorder) and by adding other intermediate ranks, such as brigade, cohort, section, or tribe. Given in full, the zoological hierarchy for the timber wolf of the Canadian subarctic would be as follows:

Kingdom Animalia

Subkingdom Metazoa

Phylum Chordata

Subphylum Vertebrata

Superclass Tetrapoda

Class Mammalia

Subclass Theria

Infraclass Eutheria

Cohort Ferungulata

Superorder Ferae

Order Carnivora

Suborder Fissipeda

Superfamily Canoidea

Family Canidae

Subfamily Caninae

Tribe (none described for this group)

Genus Canis

Subgenus (none described for this group)

Species Canis lupus (wolf)

Subspecies Canis lupus occidentalis (northern timber wolf)

Although the name of the species is binomial (e.g., Canis lupus) and that of the subspecies trinomial (C. lupus occidentalis for the northern timber wolf, C. lupus lupus for the northern European wolf), all other names are single words. In zoology, convention dictates that the names of superfamilies end in -oidea, and the code dictates that the names of families end in -idae, those of subfamilies in -inae, and those of tribes in -ini. Unfortunately, there are no widely accepted rules for other major divisions of living things, because each major group of animals and plants has its own taxonomic history and old names tend to be preserved. Apart from a few accepted endings, the names of groups of high rank are not standardized and must be memorized.

The discovery of a living coelacanth fish of the genus Latimeria in 1938 caused virtually no disturbance of the accepted classification, since the suborder Coelacanthi was already well known from fossils. When certain unusual worms were discovered in the depths of the oceans about 10 years later, however, it was necessary to create a new phylum, Pogonophora, for them since they showed no close affinities to any other known animals. The phylum Pogonophora, as usually classified, has one class—the animals in the phylum are relatively similar—but there are two orders, several families and genera, and more than 100 species. Both of these examples have been widely accepted by authorities in their respective areas of taxonomy and may be considered stable taxa.

It cannot be too strongly emphasized that there are no explicit taxonomic characters that define a phylum, class, order, or other rank. A feature characteristic of one phylum may vary in another phylum among closely related members of a class, order, or some lower group. The complex carbohydrate cellulose is characteristic of two kingdoms of plants, but among animals cellulose occurs only in one subphylum of one phylum. It would simplify the work of the taxonomist if characters diagnostic of phylum rank in animals were always taken from one feature, the skeleton, for example; those of class rank, from the respiratory organs; and so on down the taxonomic hierarchy. Such a system, however, would produce an unnatural classification.

The taxonomist must first recognize natural groups and then decide on the rank that should be assigned them. Are sea squirts, for instance, so clearly linked by the structure of the extraordinary immature form (larva) to the phylum Chordata, which includes all the vertebrates, that they should be called a subphylum, or should their extremely modified adult organization be deemed more important, with the result that sea squirts might be recognized as a separate phylum, albeit clearly related to the Chordata? At present, this sort of question has no precise answer.

Some biologists believe that “numerical taxonomy,” a system of quantifying characteristics of taxa and subjecting the results to multivariate analysis, may eventually produce quantitative measures of overall differences among groups and that agreement can be achieved so as to establish the maximal difference allowed each taxonomic level. Although such agreement may be possible, many difficulties exist. An order in one authority’s classification may be a superorder or class in another. Most of the established classifications of the better-known groups result from a general consensus among practicing taxonomists. It follows that no complete definition of a group can be made until the group itself has been recognized, after which its common (or most usual) characters can be formally stated. As further information is obtained about the group, it is subject to taxonomic revision.

Nomenclature

Communication among biologists requires a recognized nomenclature, especially for the units in most common use. The internationally accepted taxonomic nomenclature is the Linnaean system, which, although founded on Linnaeus’s rules and procedures, has been greatly modified through the years. There are separate international codes of nomenclature in botany (first published in 1901), in zoology (1906), and in microbiology (bacteria and viruses, 1948). The Linnaean binomial system is not employed for viruses. There is also a code, which was established in 1953, for the nomenclature of cultivated plants, many of which are artificially produced and are unknown in the wild.

The codes, the authority for each of which stems from a corresponding international congress, differ in various details, but all include the following elements: the naming of species by two words treated as Latin; a law of priority that the first validly published and validly binomial name for a given taxon is the correct one and that any others must become synonyms; recognition that a valid binomen can apply to only one taxon, so that a name may be used both in botany and in zoology but for only one plant taxon and one animal taxon; that if taxonomic opinion about the status of a taxon is changed, the valid name can change also; and, lastly, that the exact sense in which a name is used be determined by reference to a type. Rules are also given for the obligate categories of the hierarchy and for what constitutes valid publication of a name. Finally, recommendations are given on the process of deriving names.

Linnaeus believed that there were not more than a few thousand genera of living things, each with some clearly marked character, and that the good taxonomist could memorize them all, especially if their names were well chosen. Thus, although the naming of the species might often involve much research, the genus at least could be easily found.

At the present time, in many taxa, the species has a definite biological meaning: it is defined as a group of individuals that can breed among themselves but do not normally breed with other forms. Among microorganisms and other groups in which sexual reproduction need not occur, this criterion fails.

In botanical practice, matters more usually resemble the Linnean situation. Many sorts of chromosomal variants (individuals with different arrangements of chromosomes, or hereditary material, which prevent interbreeding) and marked ecotypes (individuals whose external form is affected by the conditions of soil, moisture, and other environmental factors), as well as other forms, that would clearly be classified as separate species by the zoologist may be lumped together unrecognized or considered subspecies by the botanist. Botanists commonly use the terms variety and form to designate genetically controlled variants within plant populations below the subspecies level.

The use of a strictly biological species definition would enormously increase rather than reduce the number of names in use in botany. A recognized species of flowering plant may consist of several “chromosomal races”—i.e., identical in external appearance but genetically incompatible and, thus, effectively separate species. Such various forms are often identifiable only by cytological examination, which requires fresh material and extensive laboratory work. Many botanists have said that there has been so little stability in the accepted nomenclature that further upheavals would be intolerable and render identification impossible for many applied botanists who may not require such refinements. To postpone recognition of such forms, however, will probably cause upheaval in the future.

Some species of birds are widespread over the archipelagos of the southwest Pacific, where nearly every island may have a form sufficiently distinct to be given some kind of taxonomic recognition. For example, 73 races are currently recognized for the golden whistler (Pachycephala pectoralis). Before the realization that species could vary geographically, each island form was named as a separate species (as many of the races of P. pectoralis actually were). It is often believed—and often it is only belief rather than fact—that all of these now genetically isolated populations arose as local differentiations of a single stock. Thus, they are now usually classed in zoological usage as subspecies of one polytypic species. The term polytypic indicates that a separate description (and type specimen) is needed for each of the distinct populations, instead of one for the entire species. The use of a trinomial designation for each subspecies (e.g., Pachycephala pectoralis bougainvillei) indicates that it is regarded as simply a local representative (in this case, on Bougainville Island in the Solomons) of a more widely distributed species. The decision on whether to consider such island forms as representatives of one species depends partly on whether, in the judgment of the taxonomist, populations from adjacent islands are sufficiently similar to allow free interbreeding.

Verification and validation by type specimens

The determination of the exact organism designated by a particular name usually requires more than the mere reading of the description or the definition of the taxon to which the name applies. New forms, which may have become known since the description was written, may differ in characteristics not originally considered, or later workers may discover, by inspection of the original material, that the original author inadvertently confused two or more forms. No description can be guaranteed to be exhaustive for all time. Validation of the use of a name requires examination of the original specimen. It must, therefore, be unambiguously designated.

At one time authors might have taken their descriptions from a series of specimens or partly (or even wholly) from other authors’ descriptions or figures, as Linnaeus often did. Much of the controversy over the validity of certain names in current use, especially those dating from the late 18th century, stems from the difficulty in determining the identity of the material used by the original authors. In modern practice, a single type specimen must be designated for a new species or subspecies name. The type should always be placed in a reliable public institution, where it can be properly cared for and made available to taxonomists. For many microorganisms, type cultures are maintained in qualified institutions. Because of the short generation time of microorganisms, however, they may actually evolve during storage.

A complex nomenclature is applied to the different sorts of type specimens. The holotype is a single specimen designated by the original describer of the form (a species or subspecies only) and available to those who want to verify the status of other specimens. When no holotype exists, as is frequently the case, a neotype is selected and so designated by someone who subsequently revises the taxon, and the neotype occupies a position equivalent to that of the holotype. The first type validly designated has priority over all other type specimens. Paratypes are specimens used, along with the holotype, in the original designation of a new form; they must be part of the same series (i.e., collected at the same immediate locality and at the same time) as the holotype.

For a taxon above the species level, the type is a taxon of the next lower rank. For a genus, for instance, it is a species. From the level of the genus to that of the superfamily there are rules regarding the formation of a group name from the name of the type group. The genus Homo (human beings) is the type genus of the family Hominidae, for example, and the code forbids its removal from the family Hominidae as long as the Hominidae is treated as a valid family and the name Homo is taxonomically valid. Whatever the remainder of its contents, the family that contains the genus Homo must be the Hominidae.

Indiscriminate collecting is of little use today, but huge areas of Earth are still poorly known biologically, at least as far as many groups are concerned, and there remain many groups for which the small number of properly collected and prepared specimens precludes any thorough taxonomic analysis. Even in well-studied groups, such as the higher vertebrates, new methods of analyzing material often necessitate special collecting. The determination of variation within species or populations may necessitate the study of more specimens than are available, even when (as is usual) the specialist can utilize material from many institutions. Usually, collecting is done to fill gaps (in geographical range, geological formations, or taxonomic categories) already brought to light by specialists reviewing the available material. The well-informed collector of living things knows where to go, what to look for, and how to spot anything especially valuable or extraordinary.

The actual techniques of collecting and preserving vary greatly from one group of organisms to another—soil protozoa, fungi, or pines are neither collected nor preserved in the same manner as birds. Some animals can be preserved only in weak alcohol, but others macerate (decompose) in it. Certain earthworms “preserved” in weak alcohol simply flow out of their own skins when lifted out. Special methods are used after long experience to preserve characters of special value in taxonomy. Some methods make specimens difficult to observe; this is especially true of material that has to be sectioned or otherwise made into preparations suitable for microscopic observation.

After taxonomic material has been collected and preserved, its value can be lost unless it is accurately and completely labelled. Only rarely is unlabelled or insufficiently labelled material of any use. The taxonomist normally must know the locality of collection of each specimen (or lot of specimens), often the habitat (e.g., type of forest, marsh, type of seawater), the date, the name of the collector, and the original field number given to the specimen or lot. To this information is added the catalog number of the collection and the sex (if not already determined in the field and if relevant). The scientific identity of the specimen, as determined by an acknowledged specialist, is usually added to the label at the museum. Also included is the name of the specialist who identified the specimen. Later revisions of the classification and additional knowledge of the organism may result in later alterations of the scientific name, but the original labels must still be kept unaltered.

Other information may also be required. For example, the males and females of some insect groups are extremely different in appearance, and males and females of the same species may have to be identified. The capture of a pair in the wild actually in copulation gives a strong (but, surprisingly, not absolute) indication that the male and female belong to the same species; the labels of each specimen (if they are separated) indicate the specimen with which it was mating."

Taxonomy - Ranks

Posted from britannica.com

Posted 5 y ago

Responses: 3

Read This Next

World History

World History Science

Science Animals

Animals