12

12

0

THE "Colonel's" MEDAL OF HONOR SERIES (Covering the period from 1861 to 1862 in alphabetic order)

Civil War

Seaman Christopher Brennan, U.S. Navy, USS Mississippi (temporarily assigned USS Colorado), Year of Action: 1862, Location of Action: Forts Jackson & St. Philip & New Orleans, LA

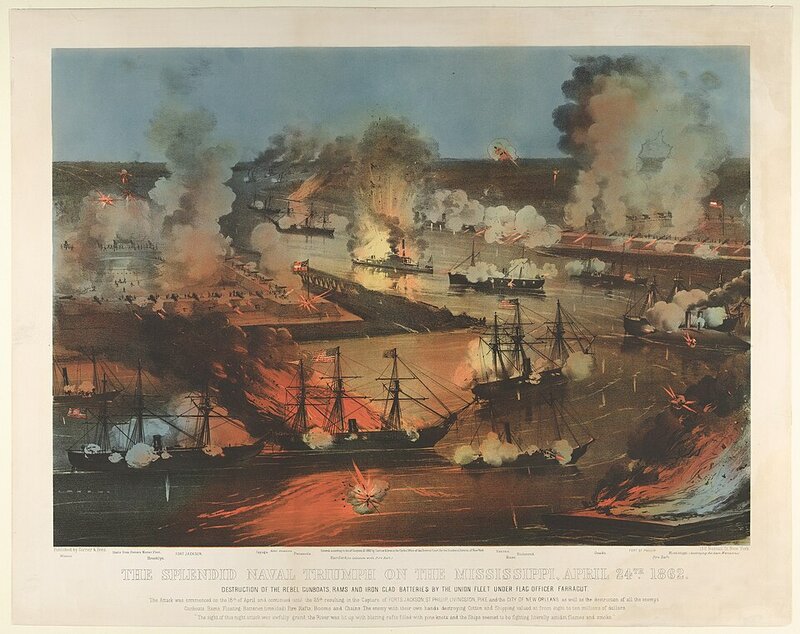

Christopher Brennan (born c. 1832, date of death unknown) was a Union Navy sailor in the American Civil War and a recipient of the U.S. military's highest decoration, the Medal of Honor, for his actions at the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip. (1st and 2ns Picture Below)

Born in about 1832 in Ireland, Brennan joined the US Navy from Boston, Massachusetts in May 1861. He initially served as a seaman on the USS Colorado. At the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip near New Orleans on April 24, 1862, he joined the USS Mississippi and manned one of that ship's guns through the engagement. His commanding officer stated that he "was the life and soul of the gun's crew." For this action, he was awarded the Medal of Honor a year later on July 10, 1863. Brennan re-enlisted twice more, and was promoted to Acting Master's Mate in November 1863. He deserted the Navy in August 1864, and the remainder of his life is unknown.

Brennan's official Medal of Honor citation reads:

The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to Seaman Christopher Brennan, United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving on board the U.S.S. MISSISSIPPI during attacks on Forts Jackson and St. Philip, Louisiana, and during the taking of New Orleans, 24 – 25 April 1862. Taking part in the actions which resulted in the damaging of the Mississippi and several casualties on it, Seaman Brennan showed skill and courage throughout the entire engagements which resulted in the taking of St. Philip and Jackson and in the surrender of New Orleans.

The Battle - Fort Jackson & Fort St. Philip

First phase: the bombardment, April 18 through 23

Porter's 21 mortar schooners were in place on April 18. They were located close to the river banks downstream from the barrier chain, which was still in place. Their tops were covered with bushes for camouflage; though this was soon stripped away by the shock of the mortar fire. Commencing in the early morning, the mortars kept up a steady fire all day. Porter had specified a rate of a shot every ten minutes from each mortar, which would have kept a shot in the air throughout the bombardment. While the rate could not be maintained, more than 1400 shots were fired on the first day. The rate of fire was somewhat less on subsequent days.

The fuses in the shells proved to be unreliable, and many of the shells exploded prematurely. To eliminate the problem, on the second and subsequent days of the bombardment, Porter ordered that all fuses should be cut to full length. While the shells hit the ground before exploding, they sank into the soft earth, muffling the effects of the blast.

Probably because it was nearer to the Federal mortars, Fort Jackson suffered more damage than did Fort St. Philip, but even there it was minimal. Only seven pieces of artillery were disabled, and only two men were killed during the bombardment. Return fire on Porter's vessels was about equally ineffective; one schooner (USS Maria J. Carlton) was sunk, and one man was killed by enemy action (another man died when he fell from the rigging.)

Porter had rashly promised Welles and Fox that the mortar fleet would reduce both forts to rubble in 48 hours. Though this did not happen, and the immediate fighting capacity of the forts were only marginally affected, a survey of Fort Jackson after the battle did note the following damage:

All the scows and boats near the fort except three small ones were sunk. The drawbridge, hot shot furnaces and fresh water cisterns were destroyed. The floors of the casemates were flooded, the levee having been broken. All the platforms for pitching tents on were destroyed by fire or shells. All the casemates were cracked (the roof in some places being entirely broken through) and masses of brick dislodged in numerous instances. The outer walls of the fort were cracked from top to bottom admitting daylight freely. Four guns were dismounted, eleven carriages and thirty beds and traverses injured. 1113 mortar shells and 87 round shot were counted in the solid ground of the fort and levees. 3339 mortar shells are computed to have fallen in the ditches and overflowed parts of the defenses. 1080 shells exploded in the air over the fort. 7500 bombs were fired.

Brigadier General Duncan, CSA, commanding the forts, described damage to Fort Jackson on the first day, April 18:

The quarters in the bastions were fired and burned down early in the day, as well as the quarters immediately without the fort. The citadel was set on fire and extinguished several times during the first part of the day, but later it became impossible to put out the flames, so that when the enemy ceased firing it was one burning mass, greatly endangering the magazines, which at one time were reported to be on fire. Many of the men and most of the officers lost their bedding and clothing by these fires, which greatly added to the discomforts of the overflow. The mortar fire was accurate and terrible, many of the shells falling everywhere within the fort and disabling some of our best guns. General Duncan recorded 2,997 mortar shells fired on that day.

This kind of damage made life in Fort Jackson a misery when combined with constant flooding from high water within the fort. The crew could be safe from mortar fragments and falling debris only within the dank and partially flooded casemates. Lack of shelter, food, blankets, sleeping quarters, drinkable water, along with the depressing effects of days of heavy, unanswered shelling were hard to bear. When combined with sickness and the ever-present corrosive fear, conditions were definitely a drain on morale. These factors contributed to the mutiny of the Fort Jackson garrison on April 28. This mutiny began a subsequent collapse of resistance downriver from the city. Fort St. Phillips was also surrendered, the CSS Louisiana blown up and even the Confederate fleet on Lake Pontchartrain was destroyed to avoid capture. The general collapse of morale began with the mutiny and greatly simplified the occupation of New Orleans by the Union navy.

The Confederate authorities had long believed that the Navy's ironclad ships, particularly CSS Louisiana, would render the river impregnable against assaults such as they were now experiencing. Although Louisiana was not yet finished, Generals Lovell and Duncan pressed Commodore Whittle to hurry the preparation. Acceding to their wishes against his better judgment, Whittle had the ship launched prematurely and added to Commander Mitchell's fleet even while workmen were still fitting her out. On the second day of the bombardment, she was towed (too late, her owners found that her engines were not strong enough to enable her to buck the current) to a position on the left bank, upstream from Fort St. Philip, where she became in effect a floating battery. Mitchell would not move her closer because her armor would not protect her from the plunging shot of Porter's mortars. However, because her guns could not be elevated, they could not be brought to bear on the enemy so long as they remained below the forts.

After several days of bombardment, the return fire from the forts showed no signs of slackening, so Farragut began to execute his own plan. On April 20, he ordered three of his gunboats, Kineo, Itasca, and Pinola, to break the chain blocking the river. Although they did not succeed in removing it altogether, they were able to open a gap large enough for the flag officer's purposes.

For various reasons, Farragut was not able to make his attack until the early morning of April 24.

Second phase: passing the forts

The order of the advance of the Union Fleet past the forts from the Bailey Papers, endorsed by Admiral D.G. Farragut

Having resolved to pass the forts, Farragut somewhat modified his fleet arrangements by adding two ships to Captain Bailey's first section of gunboats, thereby eliminating one of his ship sections. After the alteration, the fleet disposition was as follows:

First section, Captain Theodorus Bailey: USS Cayuga, Pensacola (ship), USS Mississippi, Oneida, Varuna, Katahdin, Kineo, and Wissahickon.

Second section (ships), Flag Officer Farragut: USS Hartford, Brooklyn, and Richmond.

Third section, Captain Henry H. Bell: USS Sciota, Iroquois, Kennebec, Pinola, Itasca, and Winona.

The ship Portsmouth was left to protect the mortar schooners.

When passing the forts, the fleet was to form two columns. The starboard column would fire on Fort St. Philip, while the port column would fire on Fort Jackson. They were not to stop and slug it out with the forts, however, but to pass by as quickly as possible. Farragut hoped that the combination of darkness and smoke would obscure the aim of the gunners in the forts, and his vessels could pass by relatively unscathed.

At approximately 03:00 on April 24, the fleet got under way and headed for the gap in the chain that had blocked the channel. Soon after passing that obstacle, they were spotted by men in the forts, which promptly opened up with all their available firepower. As Farragut had hoped, however, their aim was poor, and his fleet suffered little significant damage. His own gunners' aim was no better, of course, and the forts likewise sustained little damage. The last three gunboats in the column turned back. Itasca was disabled by a shot in her boilers and drifted out of action; the others (Pinola and Winona) turned back because dawn was breaking and not because of Rebel guns.

Admiral Farragut's second division passes the forts.

The Confederate fleet did very little in this stage of the battle. CSS Louisiana was finally able to use her guns, but with little effect. The armored ram CSS Manassas came in early and tried to engage the enemy, but the gunners in the forts made no distinction between Manassas and members of the Federal fleet, firing on friend and foe indiscriminately. Her captain, Lieutenant Commander Alexander F. Warley, therefore took his vessel back up the river, to attack when he would be fired upon by only the Union fleet.

Once past the forts, the head of the Federal column came under attack by some of the Confederate ships, while some of the vessels further back in the column were still under the fire of the forts. Because of their fragmented command structure, the Confederate ships did not coordinate their movements, so the battle degenerated into a jumble of individual ship-on-ship engagements.

Manassas rammed both USS Mississippi and USS Brooklyn, but could not disable either. As dawn broke, she found herself caught between two Union ships and was able to attack neither, so Captain Warley ordered her run ashore. The crew abandoned the vessel and set her afire. Later, she floated free from the bank, still afire, and finally sank in view of Porter's mortar schooners.

Mosher pushes the fire raft against Hartford.

The tug CSS Mosher pushed a fire raft against the flagship USS Hartford; for her daring she received a broadside from the latter that sent her to the bottom. Hartford, while attempting to avoid the fire raft, ran ashore not far upstream from Fort St. Philip. Although she was then within range of the guns of the fort, they could not be brought to bear, so the flagship was able to extinguish the flames and work her way off the bank with little significant damage.

In getting under way, Governor Moore was fouled by and ran into the Confederate tug Belle Algerine, sinking her. Attacking the Union fleet, she found USS Varuna ahead of the rest of the fleet. A long chase ensued, both ships firing on each other as Governor Moore pursued the Federal vessel. Despite losing a large part of her crew during the chase, she was eventually able to ram Varuna. The cottonclad ram Stonewall Jackson, of the River Defense Fleet, also managed to ram. Varuna was able to reach shallow water near the bank before she sank, the only vessel lost from the attacking fleet. Lieutenant Beverly Kennon, captaining Governor Moore, would have continued the fight, but his steersman had had enough and drove the ship ashore. Kennon, apparently realizing that his steersman was correct and that the ship was unable to do any more, ordered her abandoned and set afire.

CSS McRae engaged several members of the Federal fleet in an uneven contest that saw her captain, Lieutenant Commander Thomas B. Huger, mortally wounded. McRae herself was badly holed, and although she survived the battle, she later sank at her moorings in New Orleans.

None of the rest of the Confederate flotilla did any harm to the Union fleet, and most of them were sunk, either by enemy action or at their own hands. The survivors, in addition to McRae, were CSS Jackson, the ram Defiance, and the transport Diana. Two unarmed tenders were surrendered to the mortar flotilla with the forts. Louisiana also survived the battle, but was scuttled rather than be surrendered.

In summary, during the run of the fleet past the forts, the Union Navy lost one vessel, while the defenders lost twelve.

Historian John D. Winters in The Civil War in Louisiana (1963) noted that with few exceptions the Confederate fleet at New Orleans had "made a sorry showing. Self-destruction, lack of co-operation, cowardice of untrained officers, and the murderous fire of the Federal gunboats reduced the fleet to a demoralized shambles." Historian Allan Nevins argues the Confederate defenses were defective:

Confederate leaders had made a tardy, ill-coordinated effort to muster at the river barrier. Fortunately for the Union, both the naval and military auxiliaries were weak. In all their work of defense the Southerners had been hampered by poverty, disorganization, lack of skilled engineers and craftsmen, friction between State authorities and Richmond, and want of foresight.

Surrender of New Orleans and the forts

The Union fleet faced only token opposition at Chalmette and thereafter had clear sailing to New Orleans. The fourteen vessels remaining arrived there in the afternoon of April 25 and laid the city under their guns. In the meantime, General Lovell had evacuated the troops that had been in the city, so no defense was possible. Panic-stricken citizens broke into stores, burned cotton and other supplies, and destroyed much of the waterfront. The unfinished CSS Mississippi was hastily launched; it was hoped that she could be towed to Memphis, but no towboats could be found, so she was burned by order of her captain. Farragut demanded the surrender of the city. The mayor and city council tried to buck the unpleasant duty up to Lovell, but he passed it back to them. After three days of fruitless negotiations, Farragut sent two officers ashore with a detachment of sailors and marines. They went to the Custom House, where they hauled down the state flag and ran up the United States flag. That signified the official return of the city to the Union.

Meanwhile, General Butler was preparing his soldiers for an attack on the forts that were now in Farragut's rear. Commodore Porter, now in charge of the flotilla still below the forts, delivered a demand to surrender to the forts, but General Duncan refused. Accordingly, Porter again began to bombard the forts, this time in preparation for Butler's assault. However, on the night of April 29, the enlisted garrison in Fort Jackson mutinied and refused to endure any more. Although Fort St. Philip was not involved in the mutiny, the interdependence of the two forts meant that it was also affected. Unable to continue the battle, Duncan capitulated the next day.

Burning of the Confederate gunboats, rams etc. at New Orleans and Algiers on the approach of the Federal Fleet

The end of CSS Louisiana came at this time. Commander John K. Mitchell, who represented the Confederate States Navy in the vicinity of the forts, was not included in the surrender negotiations. He therefore did not consider it his duty to observe the truce that had been declared, so he ordered Louisiana to be destroyed. Set afire, she soon became undocked and floated down the river. Louisiana blew up as she passed Fort St. Philip; the blast killed one soldier in the fort.

Aftermath

Forts Jackson and St. Philip had been the shell of the Confederate defenses on the lower Mississippi, and nothing now stood between the Gulf and Memphis. After a few days spent repairing battle damage his ships had suffered, Farragut sent expeditions north to demand the surrender of other cities on the river. With no effective means of defense, Baton Rouge and Natchez complied. At Vicksburg, however, the guns of the ships could not reach the Confederate fortifications atop the bluffs, and the small army contingent that was with them could not force the issue. Farragut settled into a siege but was forced to withdraw when falling levels of the river threatened to strand his deep-water ships. Vicksburg would not fall until another year had passed.

The fall of New Orleans as a consequence of the battle may also have swayed European powers, primarily Great Britain and France, not to recognize the Confederacy diplomatically. Confederate agents abroad noted that they were generally received more coolly, if at all, after word of loss of the city reached London and Paris.

Civil War

Seaman Christopher Brennan, U.S. Navy, USS Mississippi (temporarily assigned USS Colorado), Year of Action: 1862, Location of Action: Forts Jackson & St. Philip & New Orleans, LA

Christopher Brennan (born c. 1832, date of death unknown) was a Union Navy sailor in the American Civil War and a recipient of the U.S. military's highest decoration, the Medal of Honor, for his actions at the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip. (1st and 2ns Picture Below)

Born in about 1832 in Ireland, Brennan joined the US Navy from Boston, Massachusetts in May 1861. He initially served as a seaman on the USS Colorado. At the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip near New Orleans on April 24, 1862, he joined the USS Mississippi and manned one of that ship's guns through the engagement. His commanding officer stated that he "was the life and soul of the gun's crew." For this action, he was awarded the Medal of Honor a year later on July 10, 1863. Brennan re-enlisted twice more, and was promoted to Acting Master's Mate in November 1863. He deserted the Navy in August 1864, and the remainder of his life is unknown.

Brennan's official Medal of Honor citation reads:

The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to Seaman Christopher Brennan, United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving on board the U.S.S. MISSISSIPPI during attacks on Forts Jackson and St. Philip, Louisiana, and during the taking of New Orleans, 24 – 25 April 1862. Taking part in the actions which resulted in the damaging of the Mississippi and several casualties on it, Seaman Brennan showed skill and courage throughout the entire engagements which resulted in the taking of St. Philip and Jackson and in the surrender of New Orleans.

The Battle - Fort Jackson & Fort St. Philip

First phase: the bombardment, April 18 through 23

Porter's 21 mortar schooners were in place on April 18. They were located close to the river banks downstream from the barrier chain, which was still in place. Their tops were covered with bushes for camouflage; though this was soon stripped away by the shock of the mortar fire. Commencing in the early morning, the mortars kept up a steady fire all day. Porter had specified a rate of a shot every ten minutes from each mortar, which would have kept a shot in the air throughout the bombardment. While the rate could not be maintained, more than 1400 shots were fired on the first day. The rate of fire was somewhat less on subsequent days.

The fuses in the shells proved to be unreliable, and many of the shells exploded prematurely. To eliminate the problem, on the second and subsequent days of the bombardment, Porter ordered that all fuses should be cut to full length. While the shells hit the ground before exploding, they sank into the soft earth, muffling the effects of the blast.

Probably because it was nearer to the Federal mortars, Fort Jackson suffered more damage than did Fort St. Philip, but even there it was minimal. Only seven pieces of artillery were disabled, and only two men were killed during the bombardment. Return fire on Porter's vessels was about equally ineffective; one schooner (USS Maria J. Carlton) was sunk, and one man was killed by enemy action (another man died when he fell from the rigging.)

Porter had rashly promised Welles and Fox that the mortar fleet would reduce both forts to rubble in 48 hours. Though this did not happen, and the immediate fighting capacity of the forts were only marginally affected, a survey of Fort Jackson after the battle did note the following damage:

All the scows and boats near the fort except three small ones were sunk. The drawbridge, hot shot furnaces and fresh water cisterns were destroyed. The floors of the casemates were flooded, the levee having been broken. All the platforms for pitching tents on were destroyed by fire or shells. All the casemates were cracked (the roof in some places being entirely broken through) and masses of brick dislodged in numerous instances. The outer walls of the fort were cracked from top to bottom admitting daylight freely. Four guns were dismounted, eleven carriages and thirty beds and traverses injured. 1113 mortar shells and 87 round shot were counted in the solid ground of the fort and levees. 3339 mortar shells are computed to have fallen in the ditches and overflowed parts of the defenses. 1080 shells exploded in the air over the fort. 7500 bombs were fired.

Brigadier General Duncan, CSA, commanding the forts, described damage to Fort Jackson on the first day, April 18:

The quarters in the bastions were fired and burned down early in the day, as well as the quarters immediately without the fort. The citadel was set on fire and extinguished several times during the first part of the day, but later it became impossible to put out the flames, so that when the enemy ceased firing it was one burning mass, greatly endangering the magazines, which at one time were reported to be on fire. Many of the men and most of the officers lost their bedding and clothing by these fires, which greatly added to the discomforts of the overflow. The mortar fire was accurate and terrible, many of the shells falling everywhere within the fort and disabling some of our best guns. General Duncan recorded 2,997 mortar shells fired on that day.

This kind of damage made life in Fort Jackson a misery when combined with constant flooding from high water within the fort. The crew could be safe from mortar fragments and falling debris only within the dank and partially flooded casemates. Lack of shelter, food, blankets, sleeping quarters, drinkable water, along with the depressing effects of days of heavy, unanswered shelling were hard to bear. When combined with sickness and the ever-present corrosive fear, conditions were definitely a drain on morale. These factors contributed to the mutiny of the Fort Jackson garrison on April 28. This mutiny began a subsequent collapse of resistance downriver from the city. Fort St. Phillips was also surrendered, the CSS Louisiana blown up and even the Confederate fleet on Lake Pontchartrain was destroyed to avoid capture. The general collapse of morale began with the mutiny and greatly simplified the occupation of New Orleans by the Union navy.

The Confederate authorities had long believed that the Navy's ironclad ships, particularly CSS Louisiana, would render the river impregnable against assaults such as they were now experiencing. Although Louisiana was not yet finished, Generals Lovell and Duncan pressed Commodore Whittle to hurry the preparation. Acceding to their wishes against his better judgment, Whittle had the ship launched prematurely and added to Commander Mitchell's fleet even while workmen were still fitting her out. On the second day of the bombardment, she was towed (too late, her owners found that her engines were not strong enough to enable her to buck the current) to a position on the left bank, upstream from Fort St. Philip, where she became in effect a floating battery. Mitchell would not move her closer because her armor would not protect her from the plunging shot of Porter's mortars. However, because her guns could not be elevated, they could not be brought to bear on the enemy so long as they remained below the forts.

After several days of bombardment, the return fire from the forts showed no signs of slackening, so Farragut began to execute his own plan. On April 20, he ordered three of his gunboats, Kineo, Itasca, and Pinola, to break the chain blocking the river. Although they did not succeed in removing it altogether, they were able to open a gap large enough for the flag officer's purposes.

For various reasons, Farragut was not able to make his attack until the early morning of April 24.

Second phase: passing the forts

The order of the advance of the Union Fleet past the forts from the Bailey Papers, endorsed by Admiral D.G. Farragut

Having resolved to pass the forts, Farragut somewhat modified his fleet arrangements by adding two ships to Captain Bailey's first section of gunboats, thereby eliminating one of his ship sections. After the alteration, the fleet disposition was as follows:

First section, Captain Theodorus Bailey: USS Cayuga, Pensacola (ship), USS Mississippi, Oneida, Varuna, Katahdin, Kineo, and Wissahickon.

Second section (ships), Flag Officer Farragut: USS Hartford, Brooklyn, and Richmond.

Third section, Captain Henry H. Bell: USS Sciota, Iroquois, Kennebec, Pinola, Itasca, and Winona.

The ship Portsmouth was left to protect the mortar schooners.

When passing the forts, the fleet was to form two columns. The starboard column would fire on Fort St. Philip, while the port column would fire on Fort Jackson. They were not to stop and slug it out with the forts, however, but to pass by as quickly as possible. Farragut hoped that the combination of darkness and smoke would obscure the aim of the gunners in the forts, and his vessels could pass by relatively unscathed.

At approximately 03:00 on April 24, the fleet got under way and headed for the gap in the chain that had blocked the channel. Soon after passing that obstacle, they were spotted by men in the forts, which promptly opened up with all their available firepower. As Farragut had hoped, however, their aim was poor, and his fleet suffered little significant damage. His own gunners' aim was no better, of course, and the forts likewise sustained little damage. The last three gunboats in the column turned back. Itasca was disabled by a shot in her boilers and drifted out of action; the others (Pinola and Winona) turned back because dawn was breaking and not because of Rebel guns.

Admiral Farragut's second division passes the forts.

The Confederate fleet did very little in this stage of the battle. CSS Louisiana was finally able to use her guns, but with little effect. The armored ram CSS Manassas came in early and tried to engage the enemy, but the gunners in the forts made no distinction between Manassas and members of the Federal fleet, firing on friend and foe indiscriminately. Her captain, Lieutenant Commander Alexander F. Warley, therefore took his vessel back up the river, to attack when he would be fired upon by only the Union fleet.

Once past the forts, the head of the Federal column came under attack by some of the Confederate ships, while some of the vessels further back in the column were still under the fire of the forts. Because of their fragmented command structure, the Confederate ships did not coordinate their movements, so the battle degenerated into a jumble of individual ship-on-ship engagements.

Manassas rammed both USS Mississippi and USS Brooklyn, but could not disable either. As dawn broke, she found herself caught between two Union ships and was able to attack neither, so Captain Warley ordered her run ashore. The crew abandoned the vessel and set her afire. Later, she floated free from the bank, still afire, and finally sank in view of Porter's mortar schooners.

Mosher pushes the fire raft against Hartford.

The tug CSS Mosher pushed a fire raft against the flagship USS Hartford; for her daring she received a broadside from the latter that sent her to the bottom. Hartford, while attempting to avoid the fire raft, ran ashore not far upstream from Fort St. Philip. Although she was then within range of the guns of the fort, they could not be brought to bear, so the flagship was able to extinguish the flames and work her way off the bank with little significant damage.

In getting under way, Governor Moore was fouled by and ran into the Confederate tug Belle Algerine, sinking her. Attacking the Union fleet, she found USS Varuna ahead of the rest of the fleet. A long chase ensued, both ships firing on each other as Governor Moore pursued the Federal vessel. Despite losing a large part of her crew during the chase, she was eventually able to ram Varuna. The cottonclad ram Stonewall Jackson, of the River Defense Fleet, also managed to ram. Varuna was able to reach shallow water near the bank before she sank, the only vessel lost from the attacking fleet. Lieutenant Beverly Kennon, captaining Governor Moore, would have continued the fight, but his steersman had had enough and drove the ship ashore. Kennon, apparently realizing that his steersman was correct and that the ship was unable to do any more, ordered her abandoned and set afire.

CSS McRae engaged several members of the Federal fleet in an uneven contest that saw her captain, Lieutenant Commander Thomas B. Huger, mortally wounded. McRae herself was badly holed, and although she survived the battle, she later sank at her moorings in New Orleans.

None of the rest of the Confederate flotilla did any harm to the Union fleet, and most of them were sunk, either by enemy action or at their own hands. The survivors, in addition to McRae, were CSS Jackson, the ram Defiance, and the transport Diana. Two unarmed tenders were surrendered to the mortar flotilla with the forts. Louisiana also survived the battle, but was scuttled rather than be surrendered.

In summary, during the run of the fleet past the forts, the Union Navy lost one vessel, while the defenders lost twelve.

Historian John D. Winters in The Civil War in Louisiana (1963) noted that with few exceptions the Confederate fleet at New Orleans had "made a sorry showing. Self-destruction, lack of co-operation, cowardice of untrained officers, and the murderous fire of the Federal gunboats reduced the fleet to a demoralized shambles." Historian Allan Nevins argues the Confederate defenses were defective:

Confederate leaders had made a tardy, ill-coordinated effort to muster at the river barrier. Fortunately for the Union, both the naval and military auxiliaries were weak. In all their work of defense the Southerners had been hampered by poverty, disorganization, lack of skilled engineers and craftsmen, friction between State authorities and Richmond, and want of foresight.

Surrender of New Orleans and the forts

The Union fleet faced only token opposition at Chalmette and thereafter had clear sailing to New Orleans. The fourteen vessels remaining arrived there in the afternoon of April 25 and laid the city under their guns. In the meantime, General Lovell had evacuated the troops that had been in the city, so no defense was possible. Panic-stricken citizens broke into stores, burned cotton and other supplies, and destroyed much of the waterfront. The unfinished CSS Mississippi was hastily launched; it was hoped that she could be towed to Memphis, but no towboats could be found, so she was burned by order of her captain. Farragut demanded the surrender of the city. The mayor and city council tried to buck the unpleasant duty up to Lovell, but he passed it back to them. After three days of fruitless negotiations, Farragut sent two officers ashore with a detachment of sailors and marines. They went to the Custom House, where they hauled down the state flag and ran up the United States flag. That signified the official return of the city to the Union.

Meanwhile, General Butler was preparing his soldiers for an attack on the forts that were now in Farragut's rear. Commodore Porter, now in charge of the flotilla still below the forts, delivered a demand to surrender to the forts, but General Duncan refused. Accordingly, Porter again began to bombard the forts, this time in preparation for Butler's assault. However, on the night of April 29, the enlisted garrison in Fort Jackson mutinied and refused to endure any more. Although Fort St. Philip was not involved in the mutiny, the interdependence of the two forts meant that it was also affected. Unable to continue the battle, Duncan capitulated the next day.

Burning of the Confederate gunboats, rams etc. at New Orleans and Algiers on the approach of the Federal Fleet

The end of CSS Louisiana came at this time. Commander John K. Mitchell, who represented the Confederate States Navy in the vicinity of the forts, was not included in the surrender negotiations. He therefore did not consider it his duty to observe the truce that had been declared, so he ordered Louisiana to be destroyed. Set afire, she soon became undocked and floated down the river. Louisiana blew up as she passed Fort St. Philip; the blast killed one soldier in the fort.

Aftermath

Forts Jackson and St. Philip had been the shell of the Confederate defenses on the lower Mississippi, and nothing now stood between the Gulf and Memphis. After a few days spent repairing battle damage his ships had suffered, Farragut sent expeditions north to demand the surrender of other cities on the river. With no effective means of defense, Baton Rouge and Natchez complied. At Vicksburg, however, the guns of the ships could not reach the Confederate fortifications atop the bluffs, and the small army contingent that was with them could not force the issue. Farragut settled into a siege but was forced to withdraw when falling levels of the river threatened to strand his deep-water ships. Vicksburg would not fall until another year had passed.

The fall of New Orleans as a consequence of the battle may also have swayed European powers, primarily Great Britain and France, not to recognize the Confederacy diplomatically. Confederate agents abroad noted that they were generally received more coolly, if at all, after word of loss of the city reached London and Paris.

Edited 20 d ago

Posted 21 d ago

Responses: 3

Read This Next

Medal of Honor

Medal of Honor Medals

Medals Civil War

Civil War Military History

Military History Heroes

Heroes