12

12

0

THE "Colonel's" MEDAL OF HONOR SERIES (Covering the period from 1861 to 1862 in alphabetic order by last name)

Civil War

Bugler John Cook, U.S. Army, Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery, Year of Action: 1862, Home Town: Cincinnati, Ohio, Location of Action: The Battle of Antietam, Maryland.

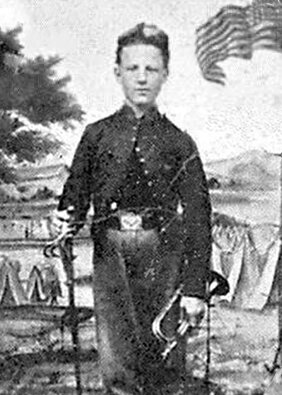

John Cook (August 10, 1847 – August 3, 1915) was a bugler in the Union Army during the American Civil War. At age 15, he earned the United States military's highest decoration, the Medal of Honor, for his actions at the Battle of Antietam.

Civil War Union Army bugler John Cook is one of the youngest Medal of Honor recipients in American history. When he was just a teen, he marched into battle with his counterparts several times, including during the bloody Battle of Antietam, where he took over as a cannoneer to help fend off a Confederate advance.

Months after the Civil War broke out, the young man, who was already working as a laborer, wanted to do his part to help, so — at age 14 and standing at a mere 4 feet 9 inches, according to historians — he enlisted in the Union Army.

Cook served with Battery B of the 4th U.S. Artillery as a bugler, but the role was like a messenger, of sorts. The bugle's high-pitched sound could reach further than human voices, so it was used to pass on officers' orders, via a system of calls and signals, to units across a battlefield.

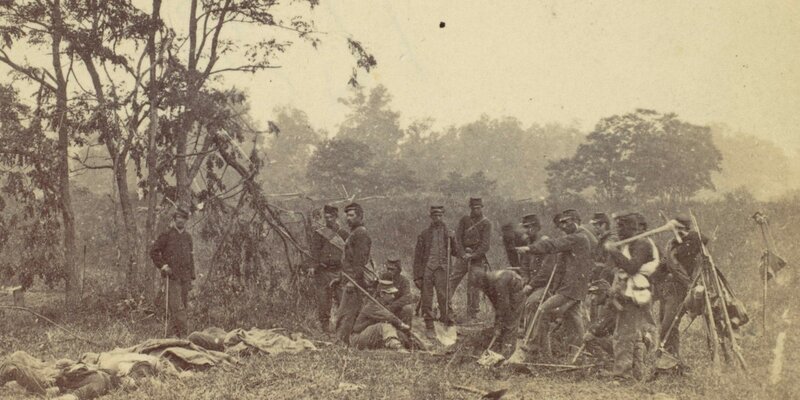

On Sept. 17, 1862, Cook's unit was among a detachment under the command of Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker during the Battle of Antietam, Maryland. As daylight broke that morning, the battery was marching south on Hagerstown Pike when it came under heavy fire from Confederate infantrymen.

During the early part of the melee, the unit's leader, Capt. Joseph B. Campbell, was injured by musket fire as he dismounted a horse. Cook, who was nearby, helped him to safety behind some haystacks before being ordered by Campbell to let Lt. James Stewart know he would have to take command of the battery.

Cook returned to the battery to pass that message on. After he completed the mission, however, he noticed that the attack had killed most of his unit's cannoneers.

Without thinking twice, the young man began loading cannons by himself until Gen. John Gibbon, who happened to be riding by, saw him doing the work alone. Gibbon — still dressed in a general's uniform — hopped off his horse and began to help. While the Confederates came dangerously close to completely taking over, Gibbon and Cook were able to successfully man the cannons and push the enemy back.

The Battle of Antietam was considered the bloodiest of the Civil War. According to a 1961 Cincinnati Enquirer newspaper article, 40 of Battery B's 100 men were either killed or injured during the fight.

Cook's heroics weren't only during the Battle of Antietam. In 1863, during the Battle of Gettysburg, he worked fervently to carry messages across a half mile of open terrain as enemy fire flew around him. He also helped destroy a damaged caisson to keep it from falling into enemy hands.

Cook received an honorable discharge from the Army in June 1864; however, he wasn't quite finished serving his country. In September 1864, Cook briefly joined the Union Navy. According to Arlington Historical Magazine, he served on the Union gunboat Peosta until June 1865, shortly after the war ended.

After his second stint at service, Cook moved back to Cincinnati, where he worked in his father's shoe shop. In 1870, he married Isabella MacBryde. They had three children, John, Rebecca and Margarette.

According to the Cincinnati Enquirer, Cook eventually got bored working in the shoe shop, so he joined the Cincinnati police before taking a job as a county recorder.

In 1887, Cook moved his family to Washington, D.C., where he worked for many years as a guard for the U.S. Government Printing Office.

On June 30, 1894 — nearly 32 years after his valiant actions during the Battle of Antietam — Cook received the Medal of Honor for his bravery during that fight.

Cook died on Aug. 3, 1915, at age 67. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery beside his wife, who died a year after he did.

His official Medal of Honor citation reads:

The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to Bugler John Cook, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 17 September 1862, while serving with Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery, in action at Antietam, Maryland. Bugler Cook volunteered at the age of 15 years to act as a cannoneer, and as such volunteer served a gun under a terrific fire of the enemy.

The Battle of Antietam, also called the Battle of Sharpsburg, particularly in the Southern United States, took place during the American Civil War on September 17, 1862, between Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union Major General George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac near Sharpsburg, Maryland, and Antietam Creek. Part of the Maryland Campaign, it was the first field army–level engagement in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War to take place on Union soil. It remains the bloodiest day in American history, with a tally of 22,727 dead, wounded, or missing on both sides. Although the Union Army suffered heavier casualties than the Confederates, the battle was a major turning point in the Union's favor.

After pursuing Confederate General Robert E. Lee into Maryland, Major General George B. McClellan of the Union Army launched attacks against Lee's army who were in defensive positions behind Antietam Creek. At dawn on September 17, Major General Joseph Hooker's corps mounted a powerful assault on Lee's left flank. Attacks and counterattacks swept across Miller's Cornfield, and fighting swirled around the Dunker Church. Union assaults against the Sunken Road eventually pierced the Confederate center, but the Federal advantage was not followed up. In the afternoon, Union Major General Ambrose Burnside's corps entered the action, capturing a stone bridge over Antietam Creek and advancing against the Confederate right. At a crucial moment, Confederate Major General A. P. Hill's division arrived from Harpers Ferry and launched a surprise counterattack, driving back Burnside and ending the battle. Although outnumbered two-to-one, Lee committed his entire force, while McClellan sent in less than three-quarters of his army, enabling Lee to fight the Federals to a standstill. During the night, both armies consolidated their lines. In spite of crippling casualties, Lee continued to skirmish with McClellan throughout September 18, while removing his battered army south of the Potomac River.

McClellan successfully turned Lee's invasion back, making the battle a strategic Union victory. From a tactical standpoint, the battle was somewhat inconclusive; the Union Army successfully repelled the Confederate invasion, but suffered heavier casualties and failed to defeat Lee's army outright. President Abraham Lincoln, unhappy with McClellan's general pattern of overcaution and his failure to pursue the retreating Lee, relieved McClellan of command in November.

Nevertheless, the strategic accomplishment was a significant turning point in the war in favor of the Union due in large part to its political ramifications: the battle's result gave Lincoln the political confidence to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. This effectively discouraged the British and French governments from recognizing the Confederacy, as neither power wished to give the appearance of supporting slavery.

Civil War

Bugler John Cook, U.S. Army, Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery, Year of Action: 1862, Home Town: Cincinnati, Ohio, Location of Action: The Battle of Antietam, Maryland.

John Cook (August 10, 1847 – August 3, 1915) was a bugler in the Union Army during the American Civil War. At age 15, he earned the United States military's highest decoration, the Medal of Honor, for his actions at the Battle of Antietam.

Civil War Union Army bugler John Cook is one of the youngest Medal of Honor recipients in American history. When he was just a teen, he marched into battle with his counterparts several times, including during the bloody Battle of Antietam, where he took over as a cannoneer to help fend off a Confederate advance.

Months after the Civil War broke out, the young man, who was already working as a laborer, wanted to do his part to help, so — at age 14 and standing at a mere 4 feet 9 inches, according to historians — he enlisted in the Union Army.

Cook served with Battery B of the 4th U.S. Artillery as a bugler, but the role was like a messenger, of sorts. The bugle's high-pitched sound could reach further than human voices, so it was used to pass on officers' orders, via a system of calls and signals, to units across a battlefield.

On Sept. 17, 1862, Cook's unit was among a detachment under the command of Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker during the Battle of Antietam, Maryland. As daylight broke that morning, the battery was marching south on Hagerstown Pike when it came under heavy fire from Confederate infantrymen.

During the early part of the melee, the unit's leader, Capt. Joseph B. Campbell, was injured by musket fire as he dismounted a horse. Cook, who was nearby, helped him to safety behind some haystacks before being ordered by Campbell to let Lt. James Stewart know he would have to take command of the battery.

Cook returned to the battery to pass that message on. After he completed the mission, however, he noticed that the attack had killed most of his unit's cannoneers.

Without thinking twice, the young man began loading cannons by himself until Gen. John Gibbon, who happened to be riding by, saw him doing the work alone. Gibbon — still dressed in a general's uniform — hopped off his horse and began to help. While the Confederates came dangerously close to completely taking over, Gibbon and Cook were able to successfully man the cannons and push the enemy back.

The Battle of Antietam was considered the bloodiest of the Civil War. According to a 1961 Cincinnati Enquirer newspaper article, 40 of Battery B's 100 men were either killed or injured during the fight.

Cook's heroics weren't only during the Battle of Antietam. In 1863, during the Battle of Gettysburg, he worked fervently to carry messages across a half mile of open terrain as enemy fire flew around him. He also helped destroy a damaged caisson to keep it from falling into enemy hands.

Cook received an honorable discharge from the Army in June 1864; however, he wasn't quite finished serving his country. In September 1864, Cook briefly joined the Union Navy. According to Arlington Historical Magazine, he served on the Union gunboat Peosta until June 1865, shortly after the war ended.

After his second stint at service, Cook moved back to Cincinnati, where he worked in his father's shoe shop. In 1870, he married Isabella MacBryde. They had three children, John, Rebecca and Margarette.

According to the Cincinnati Enquirer, Cook eventually got bored working in the shoe shop, so he joined the Cincinnati police before taking a job as a county recorder.

In 1887, Cook moved his family to Washington, D.C., where he worked for many years as a guard for the U.S. Government Printing Office.

On June 30, 1894 — nearly 32 years after his valiant actions during the Battle of Antietam — Cook received the Medal of Honor for his bravery during that fight.

Cook died on Aug. 3, 1915, at age 67. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery beside his wife, who died a year after he did.

His official Medal of Honor citation reads:

The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to Bugler John Cook, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 17 September 1862, while serving with Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery, in action at Antietam, Maryland. Bugler Cook volunteered at the age of 15 years to act as a cannoneer, and as such volunteer served a gun under a terrific fire of the enemy.

The Battle of Antietam, also called the Battle of Sharpsburg, particularly in the Southern United States, took place during the American Civil War on September 17, 1862, between Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union Major General George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac near Sharpsburg, Maryland, and Antietam Creek. Part of the Maryland Campaign, it was the first field army–level engagement in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War to take place on Union soil. It remains the bloodiest day in American history, with a tally of 22,727 dead, wounded, or missing on both sides. Although the Union Army suffered heavier casualties than the Confederates, the battle was a major turning point in the Union's favor.

After pursuing Confederate General Robert E. Lee into Maryland, Major General George B. McClellan of the Union Army launched attacks against Lee's army who were in defensive positions behind Antietam Creek. At dawn on September 17, Major General Joseph Hooker's corps mounted a powerful assault on Lee's left flank. Attacks and counterattacks swept across Miller's Cornfield, and fighting swirled around the Dunker Church. Union assaults against the Sunken Road eventually pierced the Confederate center, but the Federal advantage was not followed up. In the afternoon, Union Major General Ambrose Burnside's corps entered the action, capturing a stone bridge over Antietam Creek and advancing against the Confederate right. At a crucial moment, Confederate Major General A. P. Hill's division arrived from Harpers Ferry and launched a surprise counterattack, driving back Burnside and ending the battle. Although outnumbered two-to-one, Lee committed his entire force, while McClellan sent in less than three-quarters of his army, enabling Lee to fight the Federals to a standstill. During the night, both armies consolidated their lines. In spite of crippling casualties, Lee continued to skirmish with McClellan throughout September 18, while removing his battered army south of the Potomac River.

McClellan successfully turned Lee's invasion back, making the battle a strategic Union victory. From a tactical standpoint, the battle was somewhat inconclusive; the Union Army successfully repelled the Confederate invasion, but suffered heavier casualties and failed to defeat Lee's army outright. President Abraham Lincoln, unhappy with McClellan's general pattern of overcaution and his failure to pursue the retreating Lee, relieved McClellan of command in November.

Nevertheless, the strategic accomplishment was a significant turning point in the war in favor of the Union due in large part to its political ramifications: the battle's result gave Lincoln the political confidence to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. This effectively discouraged the British and French governments from recognizing the Confederacy, as neither power wished to give the appearance of supporting slavery.

Edited 1 d ago

Posted 1 d ago

Responses: 3

COL Mikel J. Burroughs Great history share. Almost makes me want to teach history. Nah, I'll stick to math!

(6)

Comment

(0)

Posted 1 d ago

(5)

Comment

(0)

Read This Next

Medal of Honor

Medal of Honor Medals

Medals Civil War

Civil War Military History

Military History Heroes

Heroes