14

14

0

THE "Colonel's" MEDAL OF HONOR SERIES (Covering the period from 1861 to 1862 in alphabetic order by last name)

Civil War

Second Lieutenant (Highest Rank: Captain) Charles Dearborn Copp, U.S. Army, Company C, 9th New Hampshire Infantry, Year of Action: 1862, Home Town: New Hampshire, Location of Action: Fredericksburg, Virginia.

(Check out the Historical Background on the Medal of Honor in the responses below, during the Civil War. Why there were so many given? ...more than any other American War! This one is a long read, but well worth it!)

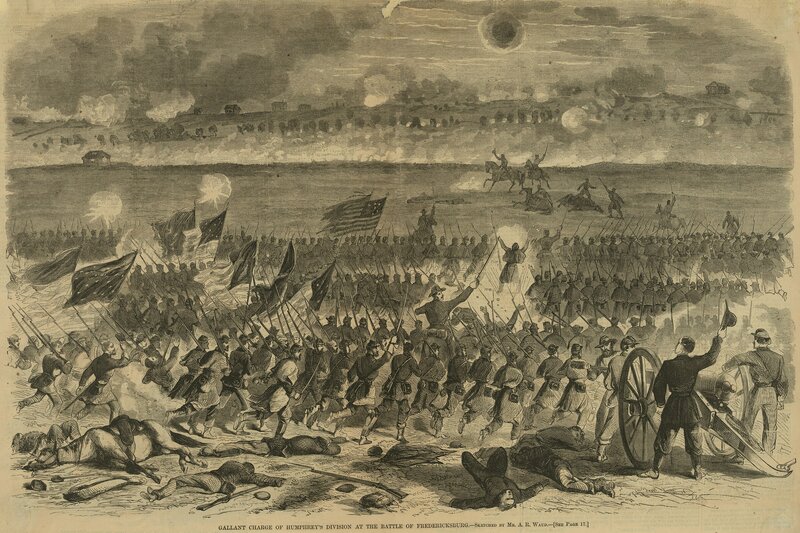

Charles Dearborn Copp (1st Picture) (April 12, 1840 – November 2, 1912) was an American soldier who served as a Union officer during the American Civil War and was awarded the Medal of Honor for extraordinary heroism at the Battle of Fredericksburg (2nd & 3rd Picture).

Born in Warren, New Hampshire, Copp enlisted in the Union Army and served as a second lieutenant in Company C of the 9th New Hampshire Infantry Regiment, later rising to captain. On December 13, 1862, during the intense fighting at Fredericksburg, Virginia, the regimental color bearer was shot down amid heavy enemy fire; Copp seized the colors and waved them to rally his faltering comrades, inspiring the regiment to hold their position. For this act of valor, he was presented with the Medal of Honor on June 28, 1890, by order of Congress, recognizing his leadership under dire circumstances.

After the war, Copp settled in Massachusetts, where he lived until his death in Clinton at age 72; he was buried in Middle Yard Cemetery in Lancaster, Massachusetts. His Medal of Honor is preserved at the Clinton Historical Society's Holder Memorial in Clinton, Massachusetts, serving as a testament to his contributions to the Union cause.

Charles Dearborn Copp was born on April 12, 1840, in Warren, Grafton County, New Hampshire, the son of Joseph Merrill Copp (1801–1887) and Hannah Herrick Brown (c. 1805–1887), who had married on October 30, 1828, in New Hampshire. His father, a farmer by trade, descended from early settlers in the region, including Joshua Copp, who arrived in Warren around 1768 and contributed to the town's civic development as a selectman and landowner.

Copp was one of at least eight children in the family, which included siblings Benjamin Kent Copp (1829–1887), Ezra Putnam Copp (1831–1900), Henry Brown Copp (1833–1929), Louisa P. Copp Hosford (1836–1900), Elbridge Jackson Copp (1844–1923), Mary Ann Copp, and Frank F. Copp (half-brother).[3] [5] The Copps belonged to a modest farming household typical of rural New Hampshire, where socioeconomic status was tied to land ownership and agricultural labor amid the town's forested hills and river valleys.

During his early childhood, Copp grew up in Warren's agrarian environment, a community of about 872 residents by 1850, centered on subsistence farming, lumbering, and limited trade, with families enduring isolation, harsh winters, and communal self-reliance before the arrival of the railroad. By the 1850 census, the family had moved to Nashua, where they adapted to an emerging industrial setting, reflecting broader shifts in New England rural life.

Before the American Civil War, Charles Dearborn Copp lived in New Hampshire, initially in Warren where he was born on April 12, 1840, before his family relocated to Nashua by mid-century.

The 1850 United States Census records the Copp family, including the ten-year-old Charles, residing in Nashua, Hillsborough County, a growing industrial center along the Merrimack River. This move aligned with broader migration patterns in the state, as families sought opportunities in manufacturing and trade.

On January 13, 1859, Copp married Harriette "Hattie" Woods in New Hampshire, marking a key personal milestone in his early adulthood. By the time of his enlistment in August 1862, official records confirm his continued residence in Nashua.

Historical records provide limited insight into Copp's pre-war occupation, with no specific profession definitively documented for his adult years prior to 1861, though later sources suggest early involvement in commerce such as book merchandising.

Charles Dearborn Copp, born in Warren, New Hampshire, but residing in Nashua since early childhood, entered military service during the Civil War amid a surge of enlistments in the state driven by patriotic fervor and federal calls for troops following early Union setbacks. In the spring of 1862, at age 22, Copp opened a recruiting office in Nashua, reflecting the widespread enthusiasm among New Hampshire civilians to support the Union cause through volunteer service. By July 1862, he had relocated to Concord, the state rendezvous point, where he contributed to assembling recruits for the newly forming Ninth New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry.

The Ninth New Hampshire Infantry was authorized in May 1862 under a War Department order for additional regiments, with recruitment ramping up across towns like Nashua, Manchester, and Concord through public meetings and speeches by prominent figures. A core group of enlistees arrived at Camp Colby in Concord by late June, under initial oversight by state officials, before Colonel Enoch Q. Fellows, a West Point graduate and veteran officer, took command on June 14. The regiment's ten companies, drawn from various counties and totaling about 975 enlisted men upon completion, underwent organization through August, with mustering into three-year federal service occurring in phases between August 6 and 23, 1862, overseen by U.S. Army inspector Colonel Seth Eastman.

Copp himself was commissioned as a second lieutenant in Company C—the regiment's designated color company—on August 10, 1862, bypassing initial private enlistment due to his recruiting efforts, and appeared in the official roster at the unit's full muster on August 23. During this period, he assisted in drilling the raw recruits, many of whom were civilians unaccustomed to military life, under the hot summer conditions at Camp Colby. Training emphasized fundamental tactics, including squad and company formations, marching maneuvers (such as forward, oblique, and double-quick steps), alignments, and facing movements, progressing from "awkward squads" for beginners to battalion-level evolutions led by experienced officers like Fellows and Lieutenant Colonel Herbert B. Titus. The men were equipped with Windsor rifles and sword bayonets, and strict discipline was enforced through daily roll calls and regulations prohibiting unauthorized firearm use, preparing the regiment for departure to Washington, D.C., on August 25, 1862.

Charles Dearborn Copp began his military service with the 9th New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry (NHVI) upon his commission as a second lieutenant in Company C on August 10, 1862, at Camp Colby in Concord, New Hampshire, where he assisted in organizing and drilling recruits drawn primarily from Nashua. Company C, designated as the color company, bore the responsibility of guarding the regimental colors, a role that placed Copp in positions of elevated danger and leadership from the outset.

Copp's promotions reflected the regiment's heavy losses and the need for experienced leadership amid ongoing campaigns. Shortly after the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, following the resignation of Colonel Enoch Q. Fellows due to illness on November 17, he advanced to first lieutenant, part of a cascade of elevations that included Lieutenant Colonel Herbert B. Titus to colonel. By mid-1864, during the Overland Campaign, Copp had risen to captain, assuming command of Company C (and later associated with Companies E and I in records) through demonstrated valor and the attrition of superior officers, such as the wounding of the first lieutenant at Antietam who never returned to duty. He mustered out as captain with the regiment on June 10, 1865, in Concord, receiving a gold watch from his company as a token of esteem just prior to discharge.

The 9th NHVI, under Copp's service, endured a grueling arc of campaigns typical of Union regiments in the Army of the Potomac and later the Ninth Corps, suffering significant casualties at key battles while contributing to major strategic advances. In September 1862, Copp participated in the Maryland Campaign, where the regiment fought at South Mountain on September 14—during which he was struck on the boot by a spent ball—and Antietam on September 17, sustaining over 100 casualties in brutal assaults that tested the unit's cohesion. The following year, in the Vicksburg Campaign (June–August 1863), the regiment marched through Mississippi, engaging in skirmishes near Jackson on July 12 and reserve duties until the fall of Vicksburg, with Copp leading his company in night alarms and picket lines that demanded vigilant discipline amid harsh conditions.

From September 1863 to January 1864, the 9th NHVI performed railroad guard duty in Kentucky, where Copp oversaw the quartering of new recruits in Paris and led detachments during expeditions against guerrillas, such as one to Mount Sterling in December 1863, fostering unit readiness through rigorous marches and rapid responses to threats. In the 1864 Overland Campaign, Copp commanded during the assault at Spotsylvania Court House on May 12, rallying scattered men to reform lines behind breastworks and aiding the wounded Major George H. Chandler under fire, actions that helped stabilize the regiment amid retreats. The subsequent Petersburg siege saw him endure trench duty, the Battle of the Crater on July 30, and illnesses from exposure, yet he rejoined to lead advances, including Hatcher's Run on October 27 where, as one of few remaining officers, he directed the right wing in constructing fortifications with a force reduced to about 150 men.

In early 1865, Copp's company supported reserve positions during the Confederate assault on Fort Stedman on March 25, aiding counterattacks that recaptured the works and captured 1,800 prisoners, before advancing into evacuated Petersburg on April 3. Throughout these engagements, Copp played a vital role in sustaining morale, frequently seizing colors to rally troops, maintaining discipline during prolonged sieges, and exemplifying resilience—such as navigating narrow escapes at South Mountain and Antietam—while the regiment's effective strength dwindled from over 900 at organization to under 200 by war's end due to battle, disease, and desertion. His leadership as color company commander emphasized the regimental colors as a focal point for unity, helping the 9th NHVI uphold its reputation for steadfast service in the Union's western and eastern theaters.

During the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862, the 9th New Hampshire Infantry, part of the 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, 9th Army Corps in the Army of the Potomac, was positioned among the Union forces launching repeated frontal assaults against Confederate defenses along Marye's Heights in Virginia. The regiment advanced across open terrain exposed to intense artillery and musket fire from entrenched Southern positions, encountering obstacles such as fences and ditches that disrupted their formation and separated some companies during the chaotic push forward.

As the 9th New Hampshire pressed toward the heights, a shell fragment struck and mortally wounded the regimental color bearer, Sergeant Edgar Dinsmore, who fell onto the national colors; several other members of the color guard were also killed in the barrage. Second Lieutenant Charles D. Copp, recently commissioned earlier that year, immediately seized the flag from beneath Dinsmore's body, raised it high, and shouted, "Forward, boys, forward!" to rally the scattered men, leading them onward while waving the colors to reform the regiment under withering Confederate fire.

This action enabled the 9th New Hampshire to partially reorganize and advance the colors to the front lines, though the regiment, like other Union units in the assault, suffered heavy casualties against the unyielding defenses, contributing to the failure of the broader attack on Marye's Heights. Copp's exposure while carrying the highly visible standard subjected him to extreme personal risk, including direct threats from shell fragments, artillery, and concentrated infantry fire that targeted such prominent figures to demoralize the enemy.

Medal of Honor Citation:

Charles D. Copp was awarded the Medal of Honor on June 28, 1890, for his actions during the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862. This issuance came nearly 28 years after the event, as part of a broader effort by Congress in the late 19th century to recognize Civil War veterans through retrospective awards. The official Medal of Honor citation reads: "Seized the regimental colors, the color bearer having been shot down, and, waving them, rallied the regiment under a heavy fire." At the time of his heroic act, Copp served as a Second Lieutenant in Company C, 9th New Hampshire Infantry Regiment.

The medal was presented to Copp on the same date as its issuance, June 28, 1890, in accordance with standard procedures for such delayed Civil War honors, which typically involved formal notification from the War Department rather than a public ceremony led by the President. These awards were often handled administratively, reflecting the era's focus on compensating and honoring aging veterans through official recognition.

(See More about Charles Dearborn Copp below in the Responses and the Battle of Fredricksburg, Virgina.)

Civil War

Second Lieutenant (Highest Rank: Captain) Charles Dearborn Copp, U.S. Army, Company C, 9th New Hampshire Infantry, Year of Action: 1862, Home Town: New Hampshire, Location of Action: Fredericksburg, Virginia.

(Check out the Historical Background on the Medal of Honor in the responses below, during the Civil War. Why there were so many given? ...more than any other American War! This one is a long read, but well worth it!)

Charles Dearborn Copp (1st Picture) (April 12, 1840 – November 2, 1912) was an American soldier who served as a Union officer during the American Civil War and was awarded the Medal of Honor for extraordinary heroism at the Battle of Fredericksburg (2nd & 3rd Picture).

Born in Warren, New Hampshire, Copp enlisted in the Union Army and served as a second lieutenant in Company C of the 9th New Hampshire Infantry Regiment, later rising to captain. On December 13, 1862, during the intense fighting at Fredericksburg, Virginia, the regimental color bearer was shot down amid heavy enemy fire; Copp seized the colors and waved them to rally his faltering comrades, inspiring the regiment to hold their position. For this act of valor, he was presented with the Medal of Honor on June 28, 1890, by order of Congress, recognizing his leadership under dire circumstances.

After the war, Copp settled in Massachusetts, where he lived until his death in Clinton at age 72; he was buried in Middle Yard Cemetery in Lancaster, Massachusetts. His Medal of Honor is preserved at the Clinton Historical Society's Holder Memorial in Clinton, Massachusetts, serving as a testament to his contributions to the Union cause.

Charles Dearborn Copp was born on April 12, 1840, in Warren, Grafton County, New Hampshire, the son of Joseph Merrill Copp (1801–1887) and Hannah Herrick Brown (c. 1805–1887), who had married on October 30, 1828, in New Hampshire. His father, a farmer by trade, descended from early settlers in the region, including Joshua Copp, who arrived in Warren around 1768 and contributed to the town's civic development as a selectman and landowner.

Copp was one of at least eight children in the family, which included siblings Benjamin Kent Copp (1829–1887), Ezra Putnam Copp (1831–1900), Henry Brown Copp (1833–1929), Louisa P. Copp Hosford (1836–1900), Elbridge Jackson Copp (1844–1923), Mary Ann Copp, and Frank F. Copp (half-brother).[3] [5] The Copps belonged to a modest farming household typical of rural New Hampshire, where socioeconomic status was tied to land ownership and agricultural labor amid the town's forested hills and river valleys.

During his early childhood, Copp grew up in Warren's agrarian environment, a community of about 872 residents by 1850, centered on subsistence farming, lumbering, and limited trade, with families enduring isolation, harsh winters, and communal self-reliance before the arrival of the railroad. By the 1850 census, the family had moved to Nashua, where they adapted to an emerging industrial setting, reflecting broader shifts in New England rural life.

Before the American Civil War, Charles Dearborn Copp lived in New Hampshire, initially in Warren where he was born on April 12, 1840, before his family relocated to Nashua by mid-century.

The 1850 United States Census records the Copp family, including the ten-year-old Charles, residing in Nashua, Hillsborough County, a growing industrial center along the Merrimack River. This move aligned with broader migration patterns in the state, as families sought opportunities in manufacturing and trade.

On January 13, 1859, Copp married Harriette "Hattie" Woods in New Hampshire, marking a key personal milestone in his early adulthood. By the time of his enlistment in August 1862, official records confirm his continued residence in Nashua.

Historical records provide limited insight into Copp's pre-war occupation, with no specific profession definitively documented for his adult years prior to 1861, though later sources suggest early involvement in commerce such as book merchandising.

Charles Dearborn Copp, born in Warren, New Hampshire, but residing in Nashua since early childhood, entered military service during the Civil War amid a surge of enlistments in the state driven by patriotic fervor and federal calls for troops following early Union setbacks. In the spring of 1862, at age 22, Copp opened a recruiting office in Nashua, reflecting the widespread enthusiasm among New Hampshire civilians to support the Union cause through volunteer service. By July 1862, he had relocated to Concord, the state rendezvous point, where he contributed to assembling recruits for the newly forming Ninth New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry.

The Ninth New Hampshire Infantry was authorized in May 1862 under a War Department order for additional regiments, with recruitment ramping up across towns like Nashua, Manchester, and Concord through public meetings and speeches by prominent figures. A core group of enlistees arrived at Camp Colby in Concord by late June, under initial oversight by state officials, before Colonel Enoch Q. Fellows, a West Point graduate and veteran officer, took command on June 14. The regiment's ten companies, drawn from various counties and totaling about 975 enlisted men upon completion, underwent organization through August, with mustering into three-year federal service occurring in phases between August 6 and 23, 1862, overseen by U.S. Army inspector Colonel Seth Eastman.

Copp himself was commissioned as a second lieutenant in Company C—the regiment's designated color company—on August 10, 1862, bypassing initial private enlistment due to his recruiting efforts, and appeared in the official roster at the unit's full muster on August 23. During this period, he assisted in drilling the raw recruits, many of whom were civilians unaccustomed to military life, under the hot summer conditions at Camp Colby. Training emphasized fundamental tactics, including squad and company formations, marching maneuvers (such as forward, oblique, and double-quick steps), alignments, and facing movements, progressing from "awkward squads" for beginners to battalion-level evolutions led by experienced officers like Fellows and Lieutenant Colonel Herbert B. Titus. The men were equipped with Windsor rifles and sword bayonets, and strict discipline was enforced through daily roll calls and regulations prohibiting unauthorized firearm use, preparing the regiment for departure to Washington, D.C., on August 25, 1862.

Charles Dearborn Copp began his military service with the 9th New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry (NHVI) upon his commission as a second lieutenant in Company C on August 10, 1862, at Camp Colby in Concord, New Hampshire, where he assisted in organizing and drilling recruits drawn primarily from Nashua. Company C, designated as the color company, bore the responsibility of guarding the regimental colors, a role that placed Copp in positions of elevated danger and leadership from the outset.

Copp's promotions reflected the regiment's heavy losses and the need for experienced leadership amid ongoing campaigns. Shortly after the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, following the resignation of Colonel Enoch Q. Fellows due to illness on November 17, he advanced to first lieutenant, part of a cascade of elevations that included Lieutenant Colonel Herbert B. Titus to colonel. By mid-1864, during the Overland Campaign, Copp had risen to captain, assuming command of Company C (and later associated with Companies E and I in records) through demonstrated valor and the attrition of superior officers, such as the wounding of the first lieutenant at Antietam who never returned to duty. He mustered out as captain with the regiment on June 10, 1865, in Concord, receiving a gold watch from his company as a token of esteem just prior to discharge.

The 9th NHVI, under Copp's service, endured a grueling arc of campaigns typical of Union regiments in the Army of the Potomac and later the Ninth Corps, suffering significant casualties at key battles while contributing to major strategic advances. In September 1862, Copp participated in the Maryland Campaign, where the regiment fought at South Mountain on September 14—during which he was struck on the boot by a spent ball—and Antietam on September 17, sustaining over 100 casualties in brutal assaults that tested the unit's cohesion. The following year, in the Vicksburg Campaign (June–August 1863), the regiment marched through Mississippi, engaging in skirmishes near Jackson on July 12 and reserve duties until the fall of Vicksburg, with Copp leading his company in night alarms and picket lines that demanded vigilant discipline amid harsh conditions.

From September 1863 to January 1864, the 9th NHVI performed railroad guard duty in Kentucky, where Copp oversaw the quartering of new recruits in Paris and led detachments during expeditions against guerrillas, such as one to Mount Sterling in December 1863, fostering unit readiness through rigorous marches and rapid responses to threats. In the 1864 Overland Campaign, Copp commanded during the assault at Spotsylvania Court House on May 12, rallying scattered men to reform lines behind breastworks and aiding the wounded Major George H. Chandler under fire, actions that helped stabilize the regiment amid retreats. The subsequent Petersburg siege saw him endure trench duty, the Battle of the Crater on July 30, and illnesses from exposure, yet he rejoined to lead advances, including Hatcher's Run on October 27 where, as one of few remaining officers, he directed the right wing in constructing fortifications with a force reduced to about 150 men.

In early 1865, Copp's company supported reserve positions during the Confederate assault on Fort Stedman on March 25, aiding counterattacks that recaptured the works and captured 1,800 prisoners, before advancing into evacuated Petersburg on April 3. Throughout these engagements, Copp played a vital role in sustaining morale, frequently seizing colors to rally troops, maintaining discipline during prolonged sieges, and exemplifying resilience—such as navigating narrow escapes at South Mountain and Antietam—while the regiment's effective strength dwindled from over 900 at organization to under 200 by war's end due to battle, disease, and desertion. His leadership as color company commander emphasized the regimental colors as a focal point for unity, helping the 9th NHVI uphold its reputation for steadfast service in the Union's western and eastern theaters.

During the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862, the 9th New Hampshire Infantry, part of the 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, 9th Army Corps in the Army of the Potomac, was positioned among the Union forces launching repeated frontal assaults against Confederate defenses along Marye's Heights in Virginia. The regiment advanced across open terrain exposed to intense artillery and musket fire from entrenched Southern positions, encountering obstacles such as fences and ditches that disrupted their formation and separated some companies during the chaotic push forward.

As the 9th New Hampshire pressed toward the heights, a shell fragment struck and mortally wounded the regimental color bearer, Sergeant Edgar Dinsmore, who fell onto the national colors; several other members of the color guard were also killed in the barrage. Second Lieutenant Charles D. Copp, recently commissioned earlier that year, immediately seized the flag from beneath Dinsmore's body, raised it high, and shouted, "Forward, boys, forward!" to rally the scattered men, leading them onward while waving the colors to reform the regiment under withering Confederate fire.

This action enabled the 9th New Hampshire to partially reorganize and advance the colors to the front lines, though the regiment, like other Union units in the assault, suffered heavy casualties against the unyielding defenses, contributing to the failure of the broader attack on Marye's Heights. Copp's exposure while carrying the highly visible standard subjected him to extreme personal risk, including direct threats from shell fragments, artillery, and concentrated infantry fire that targeted such prominent figures to demoralize the enemy.

Medal of Honor Citation:

Charles D. Copp was awarded the Medal of Honor on June 28, 1890, for his actions during the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862. This issuance came nearly 28 years after the event, as part of a broader effort by Congress in the late 19th century to recognize Civil War veterans through retrospective awards. The official Medal of Honor citation reads: "Seized the regimental colors, the color bearer having been shot down, and, waving them, rallied the regiment under a heavy fire." At the time of his heroic act, Copp served as a Second Lieutenant in Company C, 9th New Hampshire Infantry Regiment.

The medal was presented to Copp on the same date as its issuance, June 28, 1890, in accordance with standard procedures for such delayed Civil War honors, which typically involved formal notification from the War Department rather than a public ceremony led by the President. These awards were often handled administratively, reflecting the era's focus on compensating and honoring aging veterans through official recognition.

(See More about Charles Dearborn Copp below in the Responses and the Battle of Fredricksburg, Virgina.)

Edited 2 d ago

Posted 2 d ago

Responses: 4

Posted 2 d ago

(8)

Comment

(0)

Posted 2 d ago

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat between the Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia under Gen. Robert E. Lee included futile frontal attacks by the Union army on December 13 against entrenched Confederate lines, hurling themselves against a feature of the battlefield that came to be remembered as the 'sunken wall' on the heights overlooking the city. It is remembered as one of the most one-sided battles of the war, with Union casualties more than twice as heavy as those suffered by the Confederates. A visitor to the battlefield described the battle as a "butchery" to U.S. President Abraham Lincoln.

Burnside planned to cross the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg in mid-November and race to the Confederate capital of Richmond before Lee's army could stop him. Burnside needed to receive the necessary pontoon bridges in time, and Lee moved his army to block the crossings. When the Union army was finally able to build its bridges and cross under fire, direct combat within the city resulted on December 11–12. Union troops prepared to assault Confederate defensive positions south of the city and on a strongly fortified ridge just west of the city known as Marye's Heights.

On December 13, the Left Grand Division of Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin was able to pierce the first defensive line of Confederate Lt. Gen. Stonewall Jackson to the south but was finally repulsed. Burnside ordered the Right and Center Grand Divisions of major generals Edwin V. Sumner and Joseph Hooker to launch multiple frontal assaults against Lt. Gen. James Longstreet's position on Marye's Heights – all were repulsed with heavy losses. On December 15, Burnside withdrew his army, ending another failed Union campaign in the Eastern Theater.

Burnside planned to cross the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg in mid-November and race to the Confederate capital of Richmond before Lee's army could stop him. Burnside needed to receive the necessary pontoon bridges in time, and Lee moved his army to block the crossings. When the Union army was finally able to build its bridges and cross under fire, direct combat within the city resulted on December 11–12. Union troops prepared to assault Confederate defensive positions south of the city and on a strongly fortified ridge just west of the city known as Marye's Heights.

On December 13, the Left Grand Division of Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin was able to pierce the first defensive line of Confederate Lt. Gen. Stonewall Jackson to the south but was finally repulsed. Burnside ordered the Right and Center Grand Divisions of major generals Edwin V. Sumner and Joseph Hooker to launch multiple frontal assaults against Lt. Gen. James Longstreet's position on Marye's Heights – all were repulsed with heavy losses. On December 15, Burnside withdrew his army, ending another failed Union campaign in the Eastern Theater.

(6)

Comment

(0)

Posted 2 d ago

Second Lieutenant (Highest Rank: Captain) Charles Dearborn Copp, U.S. Army, Company C, 9th New Hampshire Infantry, Year of Action: 1862, Home Town: New Hampshire, Location of Action: Fredericksburg, Virginia. (Cont'd)

Following the conclusion of the Civil War, Charles D. Copp had attained the rank of captain in Company C of the 9th New Hampshire Infantry Regiment. The regiment mustered out of service on June 10, 1865, in Alexandria, Virginia, marking the end of Copp's active military duties.

Copp became a companion in the Massachusetts Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, an organization dedicated to preserving the memory of Union veterans and promoting patriotic values.

Copp first married Harriette "Hattie" E. Woods on January 13, 1855, in Nashua, New Hampshire; she died between 1900 and 1906. After the war, Copp relocated from New Hampshire to Massachusetts, settling in Clinton around 1878. There, as a widower, he married Isabel "Nellie" Sutherland, a local resident, on April 11, 1906. He worked in the textile industry for companies including Gibbs Loom Harness and Reid Co. No children are known from either marriage. His ties to the Clinton area are further evidenced by the preservation of his Medal of Honor at the Clinton Historical Society's Holder Memorial, where it serves as a key artifact in local displays of Civil War history. Copp's later associations extended to nearby Lancaster, reflecting his enduring roots in central Massachusetts.

Charles Dearborn Copp died on November 2, 1912, in Clinton, Massachusetts, at the age of 72. The cause of his death is not detailed in historical records.

He was buried in Middle Yard Cemetery, Lancaster, Worcester County, Massachusetts, in the front section, row 3. His grave is marked with a stone inscription reading "MEDAL OF HONOR CAPT CO C 9 NH INF," which commemorates his Civil War service and Medal of Honor award.

As a Union veteran and Medal of Honor recipient, Copp's burial reflected early 20th-century tributes to Civil War soldiers, influenced by organizations like the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), which promoted grave markings and local honors for comrades. His marker serves as an immediate post-mortem commemoration of his heroism at Fredericksburg.

Following the conclusion of the Civil War, Charles D. Copp had attained the rank of captain in Company C of the 9th New Hampshire Infantry Regiment. The regiment mustered out of service on June 10, 1865, in Alexandria, Virginia, marking the end of Copp's active military duties.

Copp became a companion in the Massachusetts Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, an organization dedicated to preserving the memory of Union veterans and promoting patriotic values.

Copp first married Harriette "Hattie" E. Woods on January 13, 1855, in Nashua, New Hampshire; she died between 1900 and 1906. After the war, Copp relocated from New Hampshire to Massachusetts, settling in Clinton around 1878. There, as a widower, he married Isabel "Nellie" Sutherland, a local resident, on April 11, 1906. He worked in the textile industry for companies including Gibbs Loom Harness and Reid Co. No children are known from either marriage. His ties to the Clinton area are further evidenced by the preservation of his Medal of Honor at the Clinton Historical Society's Holder Memorial, where it serves as a key artifact in local displays of Civil War history. Copp's later associations extended to nearby Lancaster, reflecting his enduring roots in central Massachusetts.

Charles Dearborn Copp died on November 2, 1912, in Clinton, Massachusetts, at the age of 72. The cause of his death is not detailed in historical records.

He was buried in Middle Yard Cemetery, Lancaster, Worcester County, Massachusetts, in the front section, row 3. His grave is marked with a stone inscription reading "MEDAL OF HONOR CAPT CO C 9 NH INF," which commemorates his Civil War service and Medal of Honor award.

As a Union veteran and Medal of Honor recipient, Copp's burial reflected early 20th-century tributes to Civil War soldiers, influenced by organizations like the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), which promoted grave markings and local honors for comrades. His marker serves as an immediate post-mortem commemoration of his heroism at Fredericksburg.

(5)

Comment

(0)

Read This Next

Medal of Honor

Medal of Honor Medals

Medals Civil War

Civil War Military History

Military History Heroes

Heroes