Posted on Mar 8, 2016

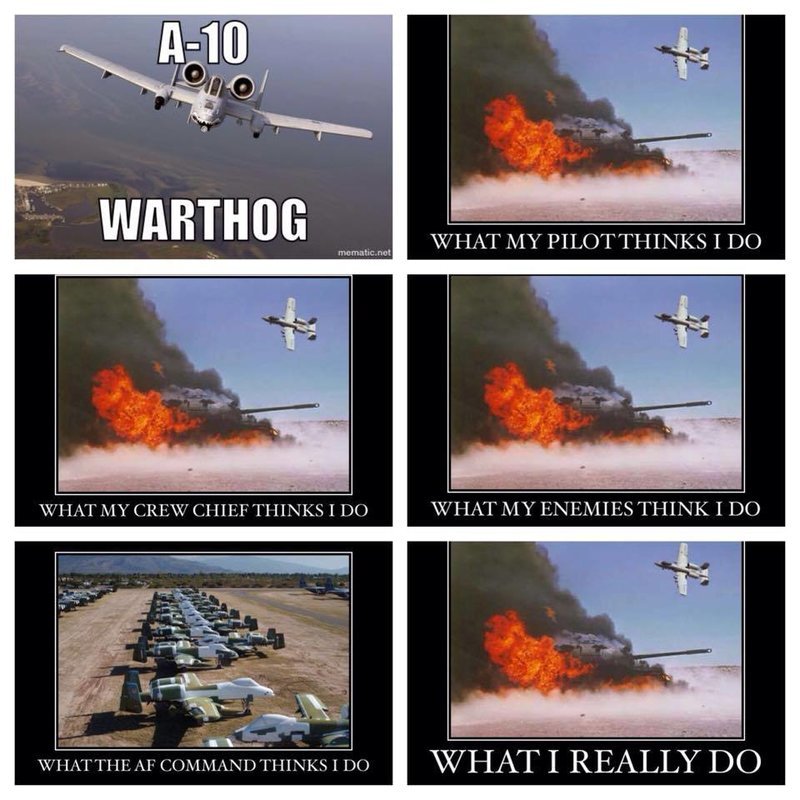

Should the A-10 Warthog be flown by Army Pilots since the Air Force does not care for it and Senator McCain sees through the AF b.s.?

38.9K

380

130

21

21

0

Senator McCain again grilled the Air Force Chief of Staff on the lack of a good replacement. The plane should be kept in service and flown by Army Aviatiors, Guard and Reserve, who often have commercial jet pilot experience already. The price of the F-35/F-16/F-18 is like comparing the price of a Bentley vs a Dodge Challenger Hellcat that can do the job better for a fraction of the price. Keeping the A-10s will save lives. Keep the extra ones not used in Guam or Diego Garcia ready for use. Put some in England to protect NATO. Hire retired air force A-10 veterans or Air Guard mechanics to fix them. If a 1950s B-52 is being kept until 2040, why not keep a 1970s A-10 around just as long? Makes sense to any Army Soldier or Marine who prefers an armored plane vs an unarmored fast mover that can't see you very well! Senator McCain and Congresswoman McSally should pursue having every single A-10 air frame out of Davis-Montham and be rebuilt to the C-model modern tank killer just like the Army rebuilds their tanks at Anniston Army Depot and makes them M1A2s. I doubt two F-16s today can destroy 32 Iraqi tanks in less than 90 minutes like the two A-10 Alpha models like did in Desert Storm back in 1991. If it works, don't fix it! Air Force, we love you, we just beg you to keep an effective weapon that Army and Marines love! I am an admirer of Air Force as a whole. http://www.stripes.com/news/mccain-lambasts-air-force-chief-of-staff-over-a-10-in-islamic-state-fight-1.397359

Edited 10 y ago

Posted 10 y ago

Responses: 36

The concept makes sense, but the AF would never go for it for political reasons. Back during the early years of Viet Nam, the Army was arming its fixed wing aircraft. The AF had a heart attack and got congress to pass a law that the Army wasn't "allowed" to have armed fixed wing aircraft. The AF was concerned that money for airframes would go to the Army instead of them.

To me, it only makes sense to give the CAS mission to the Army. It seems to be working well for the Marines. But I doubt it will ever happen.

To me, it only makes sense to give the CAS mission to the Army. It seems to be working well for the Marines. But I doubt it will ever happen.

(5)

(0)

LTC Paul Labrador

CAS (and to some extent strategic mobility) is an afterthought to the AF. They do it because the Army MAKES them do it.

As for the A-10, I agree it will never happen. While I'm sure the AF would love to offload the airframe, they will be loathe to give up the support structure (and dollars) that are required to keep the aircraft flying. It does the Army no good to take an aircraft without the mechanics, technicians, equipment and parts needed.....and the AF will NEVER give those up.

As for the A-10, I agree it will never happen. While I'm sure the AF would love to offload the airframe, they will be loathe to give up the support structure (and dollars) that are required to keep the aircraft flying. It does the Army no good to take an aircraft without the mechanics, technicians, equipment and parts needed.....and the AF will NEVER give those up.

(2)

(0)

I have long thought that the close ground support mission should be given to either the Army or the Marines. I don't mean to insult the Air Force but they have long seemed more interested in wasting billions on fancy toys.

(5)

(0)

Col Joseph Lenertz

SGT Jerrold Pesz No insult taken. You are right, the AF has wasted money on fancy toys. Just like the Army and Navy. We're all guilty of it. Look up Future Combat System, RAH66 Comanche, Joint Tactical radio System (JTRS), and XM2001 Crusader.

(2)

(0)

SGT Robert Deem

LTC Stephen Conway The Marines are getting the V/STOL variant (F-35B) to replace Harrier.

(1)

(0)

LTC Stephen Conway

Is the nuclear agreement between the United States and Iran a good or bad deal? Would it be harder or easier for Iran to develop nuclear weapons? Would it ma...

Col Joseph Lenertz - Sir, the Crusader was cancelled. President W. Bush did a Presidential Order to put the plane in production before it was a validated prototype that allowed it to continue and now we are 7 years and $160 billlion over. We got blue falconed and nothing can be done yet the A-10 could have been rebuilt for less than the $160 billion wasted. Good thing, Sir, is that I believe the ersatz peace dividend and the sequestration will go away because North Korea nuke threats, ISIL, Iran missle launches with 'Israel must be destroyed'on the missle in Hebrew and the new USSR (Russia under the new Stalinist Putin) will make us do with the rebuilding we did in the 1980s under President Reagan because the enemy will be enboldened and we will have, Democrat or Repulican, no option but to wake up and not be mr. nice guy anymore since their is a new axis of evil out there.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u4FkNbtkgps

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u4FkNbtkgps

(0)

(0)

No, but the plane should not be left to die off. They should be upgrades and overhauled. Hell, the AF made numerous upgrades and changes to the C-130 and still uses that flying sh!tcan today.

(4)

(0)

I bet the Marine Corps would like to have it also. However, I believe the A-10 should stay in Air Force inventory. The disconnect starts with the Faster, Higher, Further, Sleek and Sexy, newer is always nicer, gene that's inherent with all of us. Air Force leadership can't help it, they never really liked the A-10 because it's not a chick magnet. They fail to grasp the trend though. 4th generation asymmetric contingencies are the order of the day. That high tech, sleek, (and supposedly stealthy, the new buzz word.) F-(Jack of all Trades, Master of None) 35 will likely only punch useless holes in the sky, unable to get into the weeds where the action is. So far, as experience has shown, a small team of snake eaters with an attachment of Air Force Combat Controllers, supported by AC-130 Spectre gunships and A-10 Thunderbolt II's, can wreck havoc in counter insurgency, 4th generation warfare. The type of fighting we'll likely be involved in for the foreseeable future.

(4)

(0)

look at that bad mamma jamma up there! While I visited Osan in Korea, a friend of mine said you wanna see a bad mo fo in action? Well it was a sunday and we were bored, he took me to some of his friends who were doing live fire drills in those, and My Lord I was floored. Those are death from above right there boy, the only other plane I love more is the blackbird and that's at the smithsonian.

(4)

(0)

First, Congress would have to change the law that says how many and what type of fixed wing aircraft the Army can have.

(4)

(0)

LTC Stephen Conway

I am sure this will be worked with out since the army does have some fixed wing planes already.

(1)

(0)

I didn't vote, because I'm thinking more along the lines of a third option: There's a lot of talk about rebuilding, maintaining, the cost of maintaining, updating wear and tear, airframe stress, etc. I wonder if we aren't looking at this the wrong way. New A-10s cost around $18 million. What if the design were updated a little with modern engines, electronics, etc and new A10s were built on the same basic design? Even if it costs 30% more than the original cost to do that with upgrades, etc. we could still buy four A-10s for the cost of one F35...and the existing ones are there with trained and experienced pilots and functional as they conduct a phased replacement.

(3)

(0)

MGySgt (Join to see)

I've had the same thought for years. Not just about the A-10 but the F-16, F-15, CH-53E... I believe the ulterior reason is because the Military Industrial Complex has a chokehold on Congress and won't let it occur.

(2)

(0)

LTC Stephen Conway

MGySgt (Join to see) -

Military-Industrial Complex Speech, Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1961

Public Papers of the Presidents, Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1960, p. 1035- 1040

My fellow Americans:

Three days from now, after half a century in the service of our country, I shall lay down the responsibilities of office as, in traditional and solemn ceremony, the authority of the Presidency is vested in my successor.

This evening I come to you with a message of leave-taking and farewell, and to share a few final thoughts with you, my countrymen.

Like every other citizen, I wish the new President, and all who will labor with him, Godspeed. I pray that the coming years will be blessed with peace and prosperity for all.

Our people expect their President and the Congress to find essential agreement on issues of great moment, the wise resolution of which will better shape the future of the Nation.

My own relations with the Congress, which began on a remote and tenuous basis when, long ago, a member of the Senate appointed me to West Point, have since ranged to the intimate during the war and immediate post-war period, and, finally, to the mutually interdependent during these past eight years.

In this final relationship, the Congress and the Administration have, on most vital issues, cooperated well, to serve the national good rather than mere partisanship, and so have assured that the business of the Nation should go forward. So, my official relationship with the Congress ends in a feeling, on my part, of gratitude that we have been able to do so much together.

II.

We now stand ten years past the midpoint of a century that has witnessed four major wars among great nations. Three of these involved our own country. Despite these holocausts America is today the strongest, the most influential and most productive nation in the world. Understandably proud of this pre-eminence, we yet realize that America's leadership and prestige depend, not merely upon our unmatched material progress, riches and military strength, but on how we use our power in the interests of world peace and human betterment.

III.

Throughout America's adventure in free government, our basic purposes have been to keep the peace; to foster progress in human achievement, and to enhance liberty, dignity and integrity among people and among nations. To strive for less would be unworthy of a free and religious people. Any failure traceable to arrogance, or our lack of comprehension or readiness to sacrifice would inflict upon us grievous hurt both at home and abroad.

Progress toward these noble goals is persistently threatened by the conflict now engulfing the world. It commands our whole attention, absorbs our very beings. We face a hostile ideology -- global in scope, atheistic in character, ruthless in purpose, and insidious in method. Unhappily the danger is poses promises to be of indefinite duration. To meet it successfully, there is called for, not so much the emotional and transitory sacrifices of crisis, but rather those which enable us to carry forward steadily, surely, and without complaint the burdens of a prolonged and complex struggle -- with liberty the stake. Only thus shall we remain, despite every provocation, on our charted course toward permanent peace and human betterment.

Crises there will continue to be. In meeting them, whether foreign or domestic, great or small, there is a recurring temptation to feel that some spectacular and costly action could become the miraculous solution to all current difficulties. A huge increase in newer elements of our defense; development of unrealistic programs to cure every ill in agriculture; a dramatic expansion in basic and applied research -- these and many other possibilities, each possibly promising in itself, may be suggested as the only way to the road we wish to travel.

But each proposal must be weighed in the light of a broader consideration: the need to maintain balance in and among national programs -- balance between the private and the public economy, balance between cost and hoped for advantage -- balance between the clearly necessary and the comfortably desirable; balance between our essential requirements as a nation and the duties imposed by the nation upon the individual; balance between actions of the moment and the national welfare of the future. Good judgment seeks balance and progress; lack of it eventually finds imbalance and frustration.

The record of many decades stands as proof that our people and their government have, in the main, understood these truths and have responded to them well, in the face of stress and threat. But threats, new in kind or degree, constantly arise. I mention two only.

IV.

A vital element in keeping the peace is our military establishment. Our arms must be mighty, ready for instant action, so that no potential aggressor may be tempted to risk his own destruction.

Our military organization today bears little relation to that known by any of my predecessors in peacetime, or indeed by the fighting men of World War II or Korea.

Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry. American makers of plowshares could, with time and as required, make swords as well. But now we can no longer risk emergency improvisation of national defense; we have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions. Added to this, three and a half million men and women are directly engaged in the defense establishment. We annually spend on military security more than the net income of all United States corporations.

This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence -- economic, political, even spiritual -- is felt in every city, every State house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society.

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the militaryindustrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.

Akin to, and largely responsible for the sweeping changes in our industrial-military posture, has been the technological revolution during recent decades.

In this revolution, research has become central; it also becomes more formalized, complex, and costly. A steadily increasing share is conducted for, by, or at the direction of, the Federal government.

Today, the solitary inventor, tinkering in his shop, has been overshadowed by task forces of scientists in laboratories and testing fields. In the same fashion, the free university, historically the fountainhead of free ideas and scientific discovery, has experienced a revolution in the conduct of research. Partly because of the huge costs involved, a government contract becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity. For every old blackboard there are now hundreds of new electronic computers.

The prospect of domination of the nation's scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present

• and is gravely to be regarded.

Yet, in holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientifictechnological elite.

It is the task of statesmanship to mold, to balance, and to integrate these and other forces, new and old, within the principles of our democratic system -- ever aiming toward the supreme goals of our free society.

V.

Another factor in maintaining balance involves the element of time. As we peer into society's future, we -- you and I, and our government -- must avoid the impulse to live only for today, plundering, for our own ease and convenience, the precious resources of tomorrow. We cannot mortgage the material assets of our grandchildren without risking the loss also of their political and spiritual heritage. We want democracy to survive for all generations to come, not to become the insolvent phantom of tomorrow.

VI.

Down the long lane of the history yet to be written America knows that this world of ours, ever growing smaller, must avoid becoming a community of dreadful fear and hate, and be instead, a proud confederation of mutual trust and respect.

Such a confederation must be one of equals. The weakest must come to the conference table with the same confidence as do we, protected as we are by our moral, economic, and military strength. That table, though scarred by many past frustrations, cannot be abandoned for the certain agony of the battlefield.

Disarmament, with mutual honor and confidence, is a continuing imperative. Together we must learn how to compose differences, not with arms, but with intellect and decent purpose. Because this need is so sharp and apparent I confess that I lay down my official responsibilities in this field with a definite sense of disappointment. As one who has witnessed the horror and the lingering sadness of war -- as one who knows that another war could utterly destroy this civilization which has been so slowly and painfully built over thousands of years -- I wish I could say tonight that a lasting peace is in sight.

Happily, I can say that war has been avoided. Steady progress toward our ultimate goal has been made. But, so much remains to be done. As a private citizen, I shall never cease to do what little I can to help the world advance along that road.

VII.

So -- in this my last good night to you as your President -- I thank you for the many opportunities you have given me for public service in war and peace. I trust that in that service you find some things worthy; as for the rest of it, I know you will find ways to improve performance in the future.

You and I -- my fellow citizens -- need to be strong in our faith that all nations, under God, will reach the goal of peace with justice. May we be ever unswerving in devotion to principle, confident but humble with power, diligent in pursuit of the Nation's great goals.

To all the peoples of the world, I once more give expression to America's prayerful and continuing aspiration:

We pray that peoples of all faiths, all races, all nations, may have their great human needs satisfied; that those now denied opportunity shall come to enjoy it to the full; that all who yearn for freedom may experience its spiritual blessings; that those who have freedom will understand, also, its heavy responsibilities; that all who are insensitive to the needs of others will learn charity; that the scourges of poverty, disease and ignorance will be made to disappear from the earth, and that, in the goodness of time, all peoples will come to live together in a peace guaranteed by the binding force of mutual respect and love.

Military-Industrial Complex Speech, Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1961

Public Papers of the Presidents, Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1960, p. 1035- 1040

My fellow Americans:

Three days from now, after half a century in the service of our country, I shall lay down the responsibilities of office as, in traditional and solemn ceremony, the authority of the Presidency is vested in my successor.

This evening I come to you with a message of leave-taking and farewell, and to share a few final thoughts with you, my countrymen.

Like every other citizen, I wish the new President, and all who will labor with him, Godspeed. I pray that the coming years will be blessed with peace and prosperity for all.

Our people expect their President and the Congress to find essential agreement on issues of great moment, the wise resolution of which will better shape the future of the Nation.

My own relations with the Congress, which began on a remote and tenuous basis when, long ago, a member of the Senate appointed me to West Point, have since ranged to the intimate during the war and immediate post-war period, and, finally, to the mutually interdependent during these past eight years.

In this final relationship, the Congress and the Administration have, on most vital issues, cooperated well, to serve the national good rather than mere partisanship, and so have assured that the business of the Nation should go forward. So, my official relationship with the Congress ends in a feeling, on my part, of gratitude that we have been able to do so much together.

II.

We now stand ten years past the midpoint of a century that has witnessed four major wars among great nations. Three of these involved our own country. Despite these holocausts America is today the strongest, the most influential and most productive nation in the world. Understandably proud of this pre-eminence, we yet realize that America's leadership and prestige depend, not merely upon our unmatched material progress, riches and military strength, but on how we use our power in the interests of world peace and human betterment.

III.

Throughout America's adventure in free government, our basic purposes have been to keep the peace; to foster progress in human achievement, and to enhance liberty, dignity and integrity among people and among nations. To strive for less would be unworthy of a free and religious people. Any failure traceable to arrogance, or our lack of comprehension or readiness to sacrifice would inflict upon us grievous hurt both at home and abroad.

Progress toward these noble goals is persistently threatened by the conflict now engulfing the world. It commands our whole attention, absorbs our very beings. We face a hostile ideology -- global in scope, atheistic in character, ruthless in purpose, and insidious in method. Unhappily the danger is poses promises to be of indefinite duration. To meet it successfully, there is called for, not so much the emotional and transitory sacrifices of crisis, but rather those which enable us to carry forward steadily, surely, and without complaint the burdens of a prolonged and complex struggle -- with liberty the stake. Only thus shall we remain, despite every provocation, on our charted course toward permanent peace and human betterment.

Crises there will continue to be. In meeting them, whether foreign or domestic, great or small, there is a recurring temptation to feel that some spectacular and costly action could become the miraculous solution to all current difficulties. A huge increase in newer elements of our defense; development of unrealistic programs to cure every ill in agriculture; a dramatic expansion in basic and applied research -- these and many other possibilities, each possibly promising in itself, may be suggested as the only way to the road we wish to travel.

But each proposal must be weighed in the light of a broader consideration: the need to maintain balance in and among national programs -- balance between the private and the public economy, balance between cost and hoped for advantage -- balance between the clearly necessary and the comfortably desirable; balance between our essential requirements as a nation and the duties imposed by the nation upon the individual; balance between actions of the moment and the national welfare of the future. Good judgment seeks balance and progress; lack of it eventually finds imbalance and frustration.

The record of many decades stands as proof that our people and their government have, in the main, understood these truths and have responded to them well, in the face of stress and threat. But threats, new in kind or degree, constantly arise. I mention two only.

IV.

A vital element in keeping the peace is our military establishment. Our arms must be mighty, ready for instant action, so that no potential aggressor may be tempted to risk his own destruction.

Our military organization today bears little relation to that known by any of my predecessors in peacetime, or indeed by the fighting men of World War II or Korea.

Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry. American makers of plowshares could, with time and as required, make swords as well. But now we can no longer risk emergency improvisation of national defense; we have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions. Added to this, three and a half million men and women are directly engaged in the defense establishment. We annually spend on military security more than the net income of all United States corporations.

This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence -- economic, political, even spiritual -- is felt in every city, every State house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society.

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the militaryindustrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.

Akin to, and largely responsible for the sweeping changes in our industrial-military posture, has been the technological revolution during recent decades.

In this revolution, research has become central; it also becomes more formalized, complex, and costly. A steadily increasing share is conducted for, by, or at the direction of, the Federal government.

Today, the solitary inventor, tinkering in his shop, has been overshadowed by task forces of scientists in laboratories and testing fields. In the same fashion, the free university, historically the fountainhead of free ideas and scientific discovery, has experienced a revolution in the conduct of research. Partly because of the huge costs involved, a government contract becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity. For every old blackboard there are now hundreds of new electronic computers.

The prospect of domination of the nation's scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present

• and is gravely to be regarded.

Yet, in holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientifictechnological elite.

It is the task of statesmanship to mold, to balance, and to integrate these and other forces, new and old, within the principles of our democratic system -- ever aiming toward the supreme goals of our free society.

V.

Another factor in maintaining balance involves the element of time. As we peer into society's future, we -- you and I, and our government -- must avoid the impulse to live only for today, plundering, for our own ease and convenience, the precious resources of tomorrow. We cannot mortgage the material assets of our grandchildren without risking the loss also of their political and spiritual heritage. We want democracy to survive for all generations to come, not to become the insolvent phantom of tomorrow.

VI.

Down the long lane of the history yet to be written America knows that this world of ours, ever growing smaller, must avoid becoming a community of dreadful fear and hate, and be instead, a proud confederation of mutual trust and respect.

Such a confederation must be one of equals. The weakest must come to the conference table with the same confidence as do we, protected as we are by our moral, economic, and military strength. That table, though scarred by many past frustrations, cannot be abandoned for the certain agony of the battlefield.

Disarmament, with mutual honor and confidence, is a continuing imperative. Together we must learn how to compose differences, not with arms, but with intellect and decent purpose. Because this need is so sharp and apparent I confess that I lay down my official responsibilities in this field with a definite sense of disappointment. As one who has witnessed the horror and the lingering sadness of war -- as one who knows that another war could utterly destroy this civilization which has been so slowly and painfully built over thousands of years -- I wish I could say tonight that a lasting peace is in sight.

Happily, I can say that war has been avoided. Steady progress toward our ultimate goal has been made. But, so much remains to be done. As a private citizen, I shall never cease to do what little I can to help the world advance along that road.

VII.

So -- in this my last good night to you as your President -- I thank you for the many opportunities you have given me for public service in war and peace. I trust that in that service you find some things worthy; as for the rest of it, I know you will find ways to improve performance in the future.

You and I -- my fellow citizens -- need to be strong in our faith that all nations, under God, will reach the goal of peace with justice. May we be ever unswerving in devotion to principle, confident but humble with power, diligent in pursuit of the Nation's great goals.

To all the peoples of the world, I once more give expression to America's prayerful and continuing aspiration:

We pray that peoples of all faiths, all races, all nations, may have their great human needs satisfied; that those now denied opportunity shall come to enjoy it to the full; that all who yearn for freedom may experience its spiritual blessings; that those who have freedom will understand, also, its heavy responsibilities; that all who are insensitive to the needs of others will learn charity; that the scourges of poverty, disease and ignorance will be made to disappear from the earth, and that, in the goodness of time, all peoples will come to live together in a peace guaranteed by the binding force of mutual respect and love.

Military-Industrial Complex Speech, Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1961

Public Papers of the Presidents, Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1960, p. 1035- 1040

My fellow Americans:

Three days from now, after half a century in the service of our country, I shall lay down the responsibilities of office as, in traditional and solemn ceremony, the authority of the Presidency is vested in my successor.

This evening I come to you with a message of leave-taking and farewell, and to share a few final thoughts with you, my countrymen.

Like every other citizen, I wish the new President, and all who will labor with him, Godspeed. I pray that the coming years will be blessed with peace and prosperity for all.

Our people expect their President and the Congress to find essential agreement on issues of great moment, the wise resolution of which will better shape the future of the Nation.

My own relations with the Congress, which began on a remote and tenuous basis when, long ago, a member of the Senate appointed me to West Point, have since ranged to the intimate during the war and immediate post-war period, and, finally, to the mutually interdependent during these past eight years.

In this final relationship, the Congress and the Administration have, on most vital issues, cooperated well, to serve the national good rather than mere partisanship, and so have assured that the business of the Nation should go forward. So, my official relationship with the Congress ends in a feeling, on my part, of gratitude that we have been able to do so much together.

II.

We now stand ten years past the midpoint of a century that has witnessed four major wars among great nations. Three of these involved our own country. Despite these holocausts America is today the strongest, the most influential and most productive nation in the world. Understandably proud of this pre-eminence, we yet realize that America's leadership and prestige depend, not merely upon our unmatched material progress, riches and military strength, but on how we use our power in the interests of world peace and human betterment.

III.

Throughout America's adventure in free government, our basic purposes have been to keep the peace; to foster progress in human achievement, and to enhance liberty, dignity and integrity among people and among nations. To strive for less would be unworthy of a free and religious people. Any failure traceable to arrogance, or our lack of comprehension or readiness to sacrifice would inflict upon us grievous hurt both at home and abroad.

Progress toward these noble goals is persistently threatened by the conflict now engulfing the world. It commands our whole attention, absorbs our very beings. We face a hostile ideology -- global in scope, atheistic in character, ruthless in purpose, and insidious in method. Unhappily the danger is poses promises to be of indefinite duration. To meet it successfully, there is called for, not so much the emotional and transitory sacrifices of crisis, but rather those which enable us to carry forward steadily, surely, and without complaint the burdens of a prolonged and complex struggle -- with liberty the stake. Only thus shall we remain, despite every provocation, on our charted course toward permanent peace and human betterment.

Crises there will continue to be. In meeting them, whether foreign or domestic, great or small, there is a recurring temptation to feel that some spectacular and costly action could become the miraculous solution to all current difficulties. A huge increase in newer elements of our defense; development of unrealistic programs to cure every ill in agriculture; a dramatic expansion in basic and applied research -- these and many other possibilities, each possibly promising in itself, may be suggested as the only way to the road we wish to travel.

But each proposal must be weighed in the light of a broader consideration: the need to maintain balance in and among national programs -- balance between the private and the public economy, balance between cost and hoped for advantage -- balance between the clearly necessary and the comfortably desirable; balance between our essential requirements as a nation and the duties imposed by the nation upon the individual; balance between actions of the moment and the national welfare of the future. Good judgment seeks balance and progress; lack of it eventually finds imbalance and frustration.

The record of many decades stands as proof that our people and their government have, in the main, understood these truths and have responded to them well, in the face of stress and threat. But threats, new in kind or degree, constantly arise. I mention two only.

IV.

A vital element in keeping the peace is our military establishment. Our arms must be mighty, ready for instant action, so that no potential aggressor may be tempted to risk his own destruction.

Our military organization today bears little relation to that known by any of my predecessors in peacetime, or indeed by the fighting men of World War II or Korea.

Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry. American makers of plowshares could, with time and as required, make swords as well. But now we can no longer risk emergency improvisation of national defense; we have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions. Added to this, three and a half million men and women are directly engaged in the defense establishment. We annually spend on military security more than the net income of all United States corporations.

This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence -- economic, political, even spiritual -- is felt in every city, every State house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society.

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the militaryindustrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.

Akin to, and largely responsible for the sweeping changes in our industrial-military posture, has been the technological revolution during recent decades.

In this revolution, research has become central; it also becomes more formalized, complex, and costly. A steadily increasing share is conducted for, by, or at the direction of, the Federal government.

Today, the solitary inventor, tinkering in his shop, has been overshadowed by task forces of scientists in laboratories and testing fields. In the same fashion, the free university, historically the fountainhead of free ideas and scientific discovery, has experienced a revolution in the conduct of research. Partly because of the huge costs involved, a government contract becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity. For every old blackboard there are now hundreds of new electronic computers.

The prospect of domination of the nation's scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present

• and is gravely to be regarded.

Yet, in holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientifictechnological elite.

It is the task of statesmanship to mold, to balance, and to integrate these and other forces, new and old, within the principles of our democratic system -- ever aiming toward the supreme goals of our free society.

V.

Another factor in maintaining balance involves the element of time. As we peer into society's future, we -- you and I, and our government -- must avoid the impulse to live only for today, plundering, for our own ease and convenience, the precious resources of tomorrow. We cannot mortgage the material assets of our grandchildren without risking the loss also of their political and spiritual heritage. We want democracy to survive for all generations to come, not to become the insolvent phantom of tomorrow.

VI.

Down the long lane of the history yet to be written America knows that this world of ours, ever growing smaller, must avoid becoming a community of dreadful fear and hate, and be instead, a proud confederation of mutual trust and respect.

Such a confederation must be one of equals. The weakest must come to the conference table with the same confidence as do we, protected as we are by our moral, economic, and military strength. That table, though scarred by many past frustrations, cannot be abandoned for the certain agony of the battlefield.

Disarmament, with mutual honor and confidence, is a continuing imperative. Together we must learn how to compose differences, not with arms, but with intellect and decent purpose. Because this need is so sharp and apparent I confess that I lay down my official responsibilities in this field with a definite sense of disappointment. As one who has witnessed the horror and the lingering sadness of war -- as one who knows that another war could utterly destroy this civilization which has been so slowly and painfully built over thousands of years -- I wish I could say tonight that a lasting peace is in sight.

Happily, I can say that war has been avoided. Steady progress toward our ultimate goal has been made. But, so much remains to be done. As a private citizen, I shall never cease to do what little I can to help the world advance along that road.

VII.

So -- in this my last good night to you as your President -- I thank you for the many opportunities you have given me for public service in war and peace. I trust that in that service you find some things worthy; as for the rest of it, I know you will find ways to improve performance in the future.

You and I -- my fellow citizens -- need to be strong in our faith that all nations, under God, will reach the goal of peace with justice. May we be ever unswerving in devotion to principle, confident but humble with power, diligent in pursuit of the Nation's great goals.

To all the peoples of the world, I once more give expression to America's prayerful and continuing aspiration:

We pray that peoples of all faiths, all races, all nations, may have their great human needs satisfied; that those now denied opportunity shall come to enjoy it to the full; that all who yearn for freedom may experience its spiritual blessings; that those who have freedom will understand, also, its heavy responsibilities; that all who are insensitive to the needs of others will learn charity; that the scourges of poverty, disease and ignorance will be made to disappear from the earth, and that, in the goodness of time, all peoples will come to live together in a peace guaranteed by the binding force of mutual respect and love.

Military-Industrial Complex Speech, Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1961

Public Papers of the Presidents, Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1960, p. 1035- 1040

My fellow Americans:

Three days from now, after half a century in the service of our country, I shall lay down the responsibilities of office as, in traditional and solemn ceremony, the authority of the Presidency is vested in my successor.

This evening I come to you with a message of leave-taking and farewell, and to share a few final thoughts with you, my countrymen.

Like every other citizen, I wish the new President, and all who will labor with him, Godspeed. I pray that the coming years will be blessed with peace and prosperity for all.

Our people expect their President and the Congress to find essential agreement on issues of great moment, the wise resolution of which will better shape the future of the Nation.

My own relations with the Congress, which began on a remote and tenuous basis when, long ago, a member of the Senate appointed me to West Point, have since ranged to the intimate during the war and immediate post-war period, and, finally, to the mutually interdependent during these past eight years.

In this final relationship, the Congress and the Administration have, on most vital issues, cooperated well, to serve the national good rather than mere partisanship, and so have assured that the business of the Nation should go forward. So, my official relationship with the Congress ends in a feeling, on my part, of gratitude that we have been able to do so much together.

II.

We now stand ten years past the midpoint of a century that has witnessed four major wars among great nations. Three of these involved our own country. Despite these holocausts America is today the strongest, the most influential and most productive nation in the world. Understandably proud of this pre-eminence, we yet realize that America's leadership and prestige depend, not merely upon our unmatched material progress, riches and military strength, but on how we use our power in the interests of world peace and human betterment.

III.

Throughout America's adventure in free government, our basic purposes have been to keep the peace; to foster progress in human achievement, and to enhance liberty, dignity and integrity among people and among nations. To strive for less would be unworthy of a free and religious people. Any failure traceable to arrogance, or our lack of comprehension or readiness to sacrifice would inflict upon us grievous hurt both at home and abroad.

Progress toward these noble goals is persistently threatened by the conflict now engulfing the world. It commands our whole attention, absorbs our very beings. We face a hostile ideology -- global in scope, atheistic in character, ruthless in purpose, and insidious in method. Unhappily the danger is poses promises to be of indefinite duration. To meet it successfully, there is called for, not so much the emotional and transitory sacrifices of crisis, but rather those which enable us to carry forward steadily, surely, and without complaint the burdens of a prolonged and complex struggle -- with liberty the stake. Only thus shall we remain, despite every provocation, on our charted course toward permanent peace and human betterment.

Crises there will continue to be. In meeting them, whether foreign or domestic, great or small, there is a recurring temptation to feel that some spectacular and costly action could become the miraculous solution to all current difficulties. A huge increase in newer elements of our defense; development of unrealistic programs to cure every ill in agriculture; a dramatic expansion in basic and applied research -- these and many other possibilities, each possibly promising in itself, may be suggested as the only way to the road we wish to travel.

But each proposal must be weighed in the light of a broader consideration: the need to maintain balance in and among national programs -- balance between the private and the public economy, balance between cost and hoped for advantage -- balance between the clearly necessary and the comfortably desirable; balance between our essential requirements as a nation and the duties imposed by the nation upon the individual; balance between actions of the moment and the national welfare of the future. Good judgment seeks balance and progress; lack of it eventually finds imbalance and frustration.

The record of many decades stands as proof that our people and their government have, in the main, understood these truths and have responded to them well, in the face of stress and threat. But threats, new in kind or degree, constantly arise. I mention two only.

IV.

A vital element in keeping the peace is our military establishment. Our arms must be mighty, ready for instant action, so that no potential aggressor may be tempted to risk his own destruction.

Our military organization today bears little relation to that known by any of my predecessors in peacetime, or indeed by the fighting men of World War II or Korea.

Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry. American makers of plowshares could, with time and as required, make swords as well. But now we can no longer risk emergency improvisation of national defense; we have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions. Added to this, three and a half million men and women are directly engaged in the defense establishment. We annually spend on military security more than the net income of all United States corporations.

This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence -- economic, political, even spiritual -- is felt in every city, every State house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society.

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the militaryindustrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.

Akin to, and largely responsible for the sweeping changes in our industrial-military posture, has been the technological revolution during recent decades.

In this revolution, research has become central; it also becomes more formalized, complex, and costly. A steadily increasing share is conducted for, by, or at the direction of, the Federal government.

Today, the solitary inventor, tinkering in his shop, has been overshadowed by task forces of scientists in laboratories and testing fields. In the same fashion, the free university, historically the fountainhead of free ideas and scientific discovery, has experienced a revolution in the conduct of research. Partly because of the huge costs involved, a government contract becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity. For every old blackboard there are now hundreds of new electronic computers.

The prospect of domination of the nation's scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present

• and is gravely to be regarded.

Yet, in holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientifictechnological elite.

It is the task of statesmanship to mold, to balance, and to integrate these and other forces, new and old, within the principles of our democratic system -- ever aiming toward the supreme goals of our free society.

V.

Another factor in maintaining balance involves the element of time. As we peer into society's future, we -- you and I, and our government -- must avoid the impulse to live only for today, plundering, for our own ease and convenience, the precious resources of tomorrow. We cannot mortgage the material assets of our grandchildren without risking the loss also of their political and spiritual heritage. We want democracy to survive for all generations to come, not to become the insolvent phantom of tomorrow.

VI.

Down the long lane of the history yet to be written America knows that this world of ours, ever growing smaller, must avoid becoming a community of dreadful fear and hate, and be instead, a proud confederation of mutual trust and respect.

Such a confederation must be one of equals. The weakest must come to the conference table with the same confidence as do we, protected as we are by our moral, economic, and military strength. That table, though scarred by many past frustrations, cannot be abandoned for the certain agony of the battlefield.

Disarmament, with mutual honor and confidence, is a continuing imperative. Together we must learn how to compose differences, not with arms, but with intellect and decent purpose. Because this need is so sharp and apparent I confess that I lay down my official responsibilities in this field with a definite sense of disappointment. As one who has witnessed the horror and the lingering sadness of war -- as one who knows that another war could utterly destroy this civilization which has been so slowly and painfully built over thousands of years -- I wish I could say tonight that a lasting peace is in sight.

Happily, I can say that war has been avoided. Steady progress toward our ultimate goal has been made. But, so much remains to be done. As a private citizen, I shall never cease to do what little I can to help the world advance along that road.

VII.

So -- in this my last good night to you as your President -- I thank you for the many opportunities you have given me for public service in war and peace. I trust that in that service you find some things worthy; as for the rest of it, I know you will find ways to improve performance in the future.

You and I -- my fellow citizens -- need to be strong in our faith that all nations, under God, will reach the goal of peace with justice. May we be ever unswerving in devotion to principle, confident but humble with power, diligent in pursuit of the Nation's great goals.

To all the peoples of the world, I once more give expression to America's prayerful and continuing aspiration:

We pray that peoples of all faiths, all races, all nations, may have their great human needs satisfied; that those now denied opportunity shall come to enjoy it to the full; that all who yearn for freedom may experience its spiritual blessings; that those who have freedom will understand, also, its heavy responsibilities; that all who are insensitive to the needs of others will learn charity; that the scourges of poverty, disease and ignorance will be made to disappear from the earth, and that, in the goodness of time, all peoples will come to live together in a peace guaranteed by the binding force of mutual respect and love.

(0)

(0)

The AF NEEDS TO KEEP IT!! It's been theirs, they need to keep it. The A-10 is an AMAZING aircraft! Why don't they just upgrade it, like they do w/ other programs? I know it's expensive, but so is upgrading all of the other airframes. What's the difference?

(3)

(0)

Maj John D Benedict

If memory serves, the A-10 did get some upgrades. I'd rather see it stay in the inventory as well... http://lockheedmartin.com/us/products/a10.html

A-10 Thunderbolt II · Lockheed Martin

Since 1997, the U.S. Air Force and Lockheed Martin-led A-10 Prime Team have worked closely to upgrade the world’s premier close air support aircraft for 21st century battle.

(1)

(0)

We can't do it all. We especially can't do it all as our resources are trimmed due to congressional mandate.

The "idea" behind the F35 is good. The "bird" itself has issues. The USAF (and USMC/USN) is attempting to create a new philosophy when it comes to PILOTS. That doesn't work if we have platforms that are too diverse. The goal is to be able to grab any pilot and shove him in any bird (from a fighter/attack/cas perspective).

I LOVE the A10. Love it. But something has to get cut. The USAF chose the A10. We can't just shift the platform over to the Army. It won't work. Not how we're currently structured. It's not "logistically" feasible, even if it does appear to be the common sense solution.

Yes, I get the cost & benefit arguments, and I agree with them. I also get the philosophy arguments (from big AF) and agree with them. No one is going to be happy with the solution.

The "idea" behind the F35 is good. The "bird" itself has issues. The USAF (and USMC/USN) is attempting to create a new philosophy when it comes to PILOTS. That doesn't work if we have platforms that are too diverse. The goal is to be able to grab any pilot and shove him in any bird (from a fighter/attack/cas perspective).

I LOVE the A10. Love it. But something has to get cut. The USAF chose the A10. We can't just shift the platform over to the Army. It won't work. Not how we're currently structured. It's not "logistically" feasible, even if it does appear to be the common sense solution.

Yes, I get the cost & benefit arguments, and I agree with them. I also get the philosophy arguments (from big AF) and agree with them. No one is going to be happy with the solution.

(3)

(0)

Maj John D Benedict

I was told years ago that the USAF basically bet the farm on the F-35...so it has to work. With current budget limitations, and the investment into that airframe, something had to go. I personally would rather keep the A-10 and lose the B-1, but I don't know if the return would meet the needs for fielding the F-35. I'm not sure the answer is for US Army pilots to fly the A-10 either. Don't get me wrong, I think they could do it, but the Army doesn't view airpower the same way the Air Force does.

There is a reason we have each branch...

I responded here, and did not vote, because I don't favor either option.

There is a reason we have each branch...

I responded here, and did not vote, because I don't favor either option.

(0)

(0)

TSgt Gwen Walcott

The F-35 probably is a reasonable replacement for the Harrier and would be a good fit for the Marines (other than cost). Effort should probably be directed to fine-tuning the -B model and let the remainder go to trash. Bulk up what remains for renewal of the A-10 for further CAS operations and F22 for interceptor work

(0)

(0)

Sgt Aaron Kennedy, MS

Maj John D Benedict - That aligns with what I've seen as well. But specifically on the "F35 concept" as opposed to the F35 bird itself.

The concept is sound. The bird just doesn't meet current requirements, which makes the concept looked flawed because tech hasn't caught up with philosophy. The closer ALL pilots are to operating on "similar" aircraft, the cheaper things become in the long run. It directly parallels the "standard service weapon" argument (everyone carries an M16 variant). It doesn't really matter if you are carrying "your" weapon because you can draw one just like it from any of the service armories. If we extend that to (the right) planes... we all win.

Unfortunately the F35 (as is) is not that bird. It just doesn't do what we need it to do. Maybe 3 versions from now it will.. but not today.. combined with massive cost overruns etc.

The concept is sound. The bird just doesn't meet current requirements, which makes the concept looked flawed because tech hasn't caught up with philosophy. The closer ALL pilots are to operating on "similar" aircraft, the cheaper things become in the long run. It directly parallels the "standard service weapon" argument (everyone carries an M16 variant). It doesn't really matter if you are carrying "your" weapon because you can draw one just like it from any of the service armories. If we extend that to (the right) planes... we all win.

Unfortunately the F35 (as is) is not that bird. It just doesn't do what we need it to do. Maybe 3 versions from now it will.. but not today.. combined with massive cost overruns etc.

(0)

(0)

LTC Stephen Conway

Maj John D Benedict - i think it will change soon, sequestration will go away due to a clear and present danger!

(0)

(0)

I'm sure there are many Army aviators capable of flying the A-10. It's just not the issue DoD and Congress face. DoD faces a resource shortfall...both funds and manpower. The AF has insufficient maintenance personnel for both the aging (and ever-increasing maintenance) A-10 and the F-35. I am no zealot for the F-35, as I have made arguments on this forum that no fast mover can be as effective at CAS as the slow, low, long-loiter, and deep magazine A-10. However, the DoD budget is fixed, so whether the AF or Army sustains the A-10, there has to be a cut somewhere. Then the discussion moves to "what kind of war should we be preparing for?"

(3)

(0)

SGT Robert Deem

Col Joseph Lenertz I think you hit it right on the head there. We sometimes forget to ask that question, or even refuse to answer it honestly when it is asked. We shipped the shiny new state-of-the-art F-4(C&D) to Vietnam without a nose cannon, because dogfights were a thing of the past. Beyond-visual-range missile fights would be the order of the day and Sidewinder (AIM-9B-D) was the only close-in protection required. I just hope we're not making the same kinds of mistakes in our thinking with the F-35.

(2)

(0)

Col Joseph Lenertz

SGT Robert Deem - Yes, absolutely. I think we might be making that same mistake again.

(0)

(0)

TSgt (Join to see)

What are the costs to retain the A-10?

I'm sure there are civilian contractors in every service that are being paid 3+X what Servicemembers are being paid to do the same jobs. I'm sure every service's procurement programs can tighten their belts in order to fund the equipment that is truly effective and wanted by those who either use them or benefit by their use.

For those who point to the OH-58 Kiowa helicopter, yes it was a great CAS asset too, but the fact is that it was underpowered and thus underarmed. It could not take off with a full load of fuel AND ammo. That's what you get when you militarize a COTS airframe and hope for the best. Apples to Oranges when compared to the A-10 and its effectiveness.

I'm sure there are civilian contractors in every service that are being paid 3+X what Servicemembers are being paid to do the same jobs. I'm sure every service's procurement programs can tighten their belts in order to fund the equipment that is truly effective and wanted by those who either use them or benefit by their use.

For those who point to the OH-58 Kiowa helicopter, yes it was a great CAS asset too, but the fact is that it was underpowered and thus underarmed. It could not take off with a full load of fuel AND ammo. That's what you get when you militarize a COTS airframe and hope for the best. Apples to Oranges when compared to the A-10 and its effectiveness.

(1)

(0)

Read This Next

Aviation

Aviation Warrant Officers

Warrant Officers A-10 Pilot

A-10 Pilot A-10

A-10 A-10 Dedicated Crew Chief

A-10 Dedicated Crew Chief