13

13

0

THE "Colonel's" MEDAL OF HONOR SERIES (Covering the period from 1861 to 1862 in alphabetic order by last name)

Civil War

Assitant Surgeon (Highest Rank: Surgeon) Richard J. Curran, US Army, 33rd New York Infantry, Date of Action: 1862, Home Town: Ennis, Location of Action: The Battle of Antietam, Maryland.

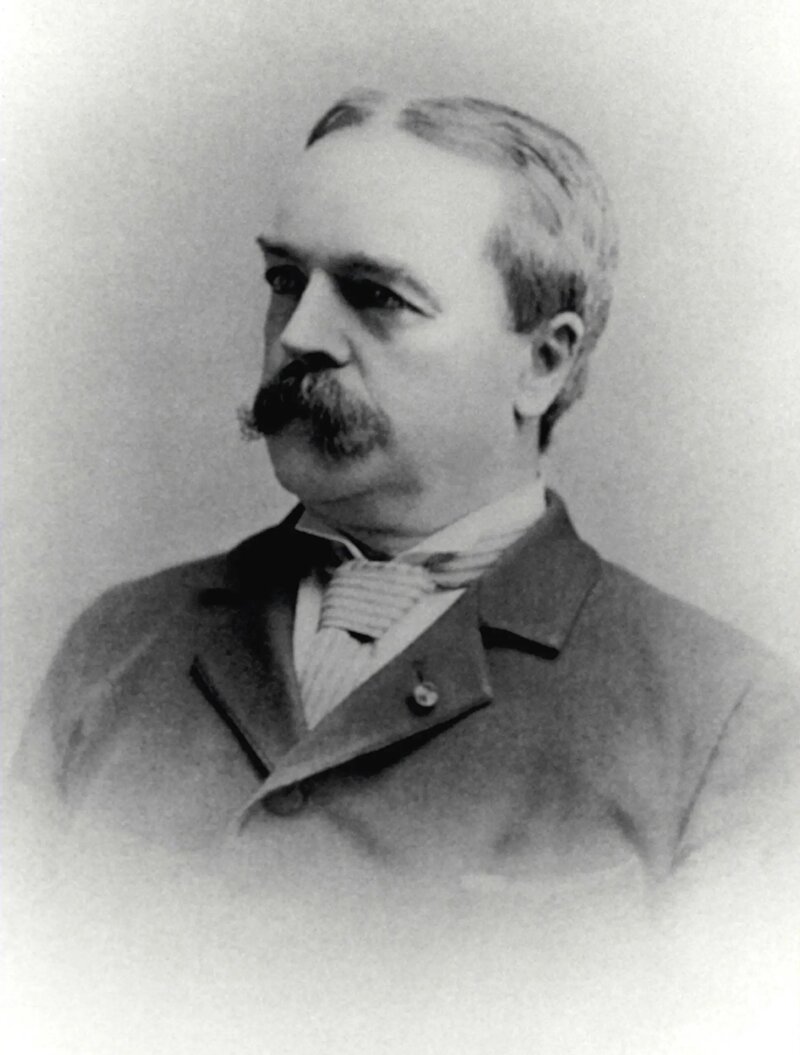

Richard J. Curran (1st Picture) (January 4, 1838 – June 1, 1915) was an Irish-American surgeon, army officer, and politician. He received the Medal of Honor for his actions during the American Civil War.

Richard Curran was born in Ennis, Co. Clare on 4th January 1838 (some sources cite 1834 as his year of birth). He emigrated with his family to the United States in 1850, and attended Harvard Medical School from where he graduated in 1859. With the outbreak of war Curran helped to raise two companies for service in upstate New York, before enlisting as a 22-year-old in the 33rd regiment. He initially mustered in as a Private in Company K on 22nd May 1861, but given his medical expertise he became Hospital Steward on 1st October that year, rising to Assistant Surgeon on 15th August 1862.

When Curran arrived on the Antietam battlefield he had little time to seek out other surgeons before his unit were ordered forward. With no instructions as to where to report, he determined to follow his regiment into the action. Irwin’s brigade, of which the 33rd New York formed a part, were ordered into fighting on the Union right, and around noon they charged towards the Confederate positions near the Dunker Church. Although initially successful, the advance came to a halt when the 33rd and 77th New York on the brigade right were struck by a savage flanking volley from the West Woods. The brigade regrouped and rallied behind a ridge east of the Hagerstown Pike, where they would remain for much of the day. However they were far from safe, and those men wounded in the assault were now subjected to a merciless fire from sharpshooters and artillery.

Richard Curran had made it through the attack safely, and now took the time to assess the situation facing the 33rd New York. He remembered: ‘The ground of the battlefield at this point was a shallow valley looking east and west. The elevated land on the south was occupied by the Confederates, while the slight ridge on the north was held by our troops and batteries. From this formation of ground it was impossible for our wounded to reach the field hospital without being exposed to the fire of the enemy.’ Curran decided that he had to do something to help these men. Despite being repeatedly told to go to the rear lest he be killed, the Irish surgeon refused and moved between the wounded, administering what aid he could.

As the day dragged on Assistant Surgeon Curran looked around to see if there were any suitable locations to gather the wounded men in a temporary field hospital. He finally found what he was looking for: ‘Close to the lines, and a little to the right, were a number of straw stacks. (2nd Picture) I visited the place and found that many of the disabled had availed themselves of this protection. Without delay I had the wounded led or carried to the place, and here, with such assistance as I could organize, although exposed to the overhead firing of shot and shell, I worked with all the zeal and strength I could muster, caring for the wounded and dying until far into the night.’ Curran remained worried that the straw stacks offering frail protection the men would catch light, as they were still being subjected to heavy fire. While the Clareman was treating the leg of one wounded soldier he briefly turned away to get a dressing for the injury. Turning back, Curran was horrified to see that the unfortunate man’s leg had in the meantime been carried off by a cannonball.

The bravery of Richard Curran at Antietam did not go unnoticed. In his official report of the fighting Colonel Irwin wrote: ‘Asst. Surg. Curran, Thirty-third New York Volunteers, was in charge of our temporary hospital, which unavoidably was under fire; but he attended faithfully to his severe duties, and I beg to mention this officer with particular commendation. His example is but too rare, most unfortunately.’ Curran stayed with the 33rd New York until they mustered out on 2nd June, 1863, but the medical man still felt he could offer more to the Union cause. Less than a month later, on 1st July, he became Assistant Surgeon in the 6th New York Cavalry, before joining up with the 9th New York Cavalry to serve as their Surgeon dating from 5th September 1864. He finished his war with the 9th, being discharged for the final time on 17th July, 1865.

Richard Curran opened a drug store in Rochester, New York after the Civil War, and became active in politics with the Republican Party. He became an Assemblyman in the New York Legislature before being elected Mayor of Rochester in 1892. Curran was awarded the Medal of Honor on the 30th March 1898, nearly 36 years after the events to which it referred. The Ennis native continued to spend his later years in Rochester, where he died on 1st January 1915 and was laid to rest in Holy Sepulchre Cemetery. (4th Picture)

Following is Curran's medal of honor citation:

The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to Assistant Surgeon Richard J. Curran, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 17 September 1862, while serving with 33d New York Infantry, in action at Antietam, Maryland. Assistant Surgeon Curran voluntarily exposed himself to great danger by going to the fighting line there succoring the wounded and helpless and conducting them to the field hospital.

The Battle of Antietam (3rd Picture), also called the Battle of Sharpsburg, particularly in the Southern United States, took place during the American Civil War on September 17, 1862, between Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union Major General George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac near Sharpsburg, Maryland, and Antietam Creek. Part of the Maryland Campaign, it was the first field army–level engagement in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War to take place on Union soil. It remains the bloodiest day in American history, with a tally of 22,727 dead, wounded, or missing on both sides. Although the Union Army suffered heavier casualties than the Confederates, the battle was a major turning point in the Union's favor.

After pursuing Confederate General Robert E. Lee into Maryland, Major General George B. McClellan of the Union Army launched attacks against Lee's army who were in defensive positions behind Antietam Creek. At dawn on September 17, Major General Joseph Hooker's corps mounted a powerful assault on Lee's left flank. Attacks and counterattacks swept across Miller's Cornfield, and fighting swirled around the Dunker Church. Union assaults against the Sunken Road eventually pierced the Confederate center, but the Federal advantage was not followed up. In the afternoon, Union Major General Ambrose Burnside's corps entered the action, capturing a stone bridge over Antietam Creek and advancing against the Confederate right. At a crucial moment, Confederate Major General A. P. Hill's division arrived from Harpers Ferry and launched a surprise counterattack, driving back Burnside and ending the battle. Although outnumbered two-to-one, Lee committed his entire force, while McClellan sent in less than three-quarters of his army, enabling Lee to fight the Federals to a standstill. During the night, both armies consolidated their lines. In spite of crippling casualties, Lee continued to skirmish with McClellan throughout September 18, while removing his battered army south of the Potomac River.

McClellan successfully turned Lee's invasion back, making the battle a strategic Union victory. From a tactical standpoint, the battle was somewhat inconclusive; the Union Army successfully repelled the Confederate invasion, but suffered heavier casualties and failed to defeat Lee's army outright. President Abraham Lincoln, unhappy with McClellan's general pattern of overcaution and his failure to pursue the retreating Lee, relieved McClellan of command in November.

Nevertheless, the strategic accomplishment was a significant turning point in the war in favor of the Union due in large part to its political ramifications: the battle's result gave Lincoln the political confidence to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. This effectively discouraged the British and French governments from recognizing the Confederacy, as neither power wished to give the appearance of supporting slavery.

Civil War

Assitant Surgeon (Highest Rank: Surgeon) Richard J. Curran, US Army, 33rd New York Infantry, Date of Action: 1862, Home Town: Ennis, Location of Action: The Battle of Antietam, Maryland.

Richard J. Curran (1st Picture) (January 4, 1838 – June 1, 1915) was an Irish-American surgeon, army officer, and politician. He received the Medal of Honor for his actions during the American Civil War.

Richard Curran was born in Ennis, Co. Clare on 4th January 1838 (some sources cite 1834 as his year of birth). He emigrated with his family to the United States in 1850, and attended Harvard Medical School from where he graduated in 1859. With the outbreak of war Curran helped to raise two companies for service in upstate New York, before enlisting as a 22-year-old in the 33rd regiment. He initially mustered in as a Private in Company K on 22nd May 1861, but given his medical expertise he became Hospital Steward on 1st October that year, rising to Assistant Surgeon on 15th August 1862.

When Curran arrived on the Antietam battlefield he had little time to seek out other surgeons before his unit were ordered forward. With no instructions as to where to report, he determined to follow his regiment into the action. Irwin’s brigade, of which the 33rd New York formed a part, were ordered into fighting on the Union right, and around noon they charged towards the Confederate positions near the Dunker Church. Although initially successful, the advance came to a halt when the 33rd and 77th New York on the brigade right were struck by a savage flanking volley from the West Woods. The brigade regrouped and rallied behind a ridge east of the Hagerstown Pike, where they would remain for much of the day. However they were far from safe, and those men wounded in the assault were now subjected to a merciless fire from sharpshooters and artillery.

Richard Curran had made it through the attack safely, and now took the time to assess the situation facing the 33rd New York. He remembered: ‘The ground of the battlefield at this point was a shallow valley looking east and west. The elevated land on the south was occupied by the Confederates, while the slight ridge on the north was held by our troops and batteries. From this formation of ground it was impossible for our wounded to reach the field hospital without being exposed to the fire of the enemy.’ Curran decided that he had to do something to help these men. Despite being repeatedly told to go to the rear lest he be killed, the Irish surgeon refused and moved between the wounded, administering what aid he could.

As the day dragged on Assistant Surgeon Curran looked around to see if there were any suitable locations to gather the wounded men in a temporary field hospital. He finally found what he was looking for: ‘Close to the lines, and a little to the right, were a number of straw stacks. (2nd Picture) I visited the place and found that many of the disabled had availed themselves of this protection. Without delay I had the wounded led or carried to the place, and here, with such assistance as I could organize, although exposed to the overhead firing of shot and shell, I worked with all the zeal and strength I could muster, caring for the wounded and dying until far into the night.’ Curran remained worried that the straw stacks offering frail protection the men would catch light, as they were still being subjected to heavy fire. While the Clareman was treating the leg of one wounded soldier he briefly turned away to get a dressing for the injury. Turning back, Curran was horrified to see that the unfortunate man’s leg had in the meantime been carried off by a cannonball.

The bravery of Richard Curran at Antietam did not go unnoticed. In his official report of the fighting Colonel Irwin wrote: ‘Asst. Surg. Curran, Thirty-third New York Volunteers, was in charge of our temporary hospital, which unavoidably was under fire; but he attended faithfully to his severe duties, and I beg to mention this officer with particular commendation. His example is but too rare, most unfortunately.’ Curran stayed with the 33rd New York until they mustered out on 2nd June, 1863, but the medical man still felt he could offer more to the Union cause. Less than a month later, on 1st July, he became Assistant Surgeon in the 6th New York Cavalry, before joining up with the 9th New York Cavalry to serve as their Surgeon dating from 5th September 1864. He finished his war with the 9th, being discharged for the final time on 17th July, 1865.

Richard Curran opened a drug store in Rochester, New York after the Civil War, and became active in politics with the Republican Party. He became an Assemblyman in the New York Legislature before being elected Mayor of Rochester in 1892. Curran was awarded the Medal of Honor on the 30th March 1898, nearly 36 years after the events to which it referred. The Ennis native continued to spend his later years in Rochester, where he died on 1st January 1915 and was laid to rest in Holy Sepulchre Cemetery. (4th Picture)

Following is Curran's medal of honor citation:

The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to Assistant Surgeon Richard J. Curran, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 17 September 1862, while serving with 33d New York Infantry, in action at Antietam, Maryland. Assistant Surgeon Curran voluntarily exposed himself to great danger by going to the fighting line there succoring the wounded and helpless and conducting them to the field hospital.

The Battle of Antietam (3rd Picture), also called the Battle of Sharpsburg, particularly in the Southern United States, took place during the American Civil War on September 17, 1862, between Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union Major General George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac near Sharpsburg, Maryland, and Antietam Creek. Part of the Maryland Campaign, it was the first field army–level engagement in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War to take place on Union soil. It remains the bloodiest day in American history, with a tally of 22,727 dead, wounded, or missing on both sides. Although the Union Army suffered heavier casualties than the Confederates, the battle was a major turning point in the Union's favor.

After pursuing Confederate General Robert E. Lee into Maryland, Major General George B. McClellan of the Union Army launched attacks against Lee's army who were in defensive positions behind Antietam Creek. At dawn on September 17, Major General Joseph Hooker's corps mounted a powerful assault on Lee's left flank. Attacks and counterattacks swept across Miller's Cornfield, and fighting swirled around the Dunker Church. Union assaults against the Sunken Road eventually pierced the Confederate center, but the Federal advantage was not followed up. In the afternoon, Union Major General Ambrose Burnside's corps entered the action, capturing a stone bridge over Antietam Creek and advancing against the Confederate right. At a crucial moment, Confederate Major General A. P. Hill's division arrived from Harpers Ferry and launched a surprise counterattack, driving back Burnside and ending the battle. Although outnumbered two-to-one, Lee committed his entire force, while McClellan sent in less than three-quarters of his army, enabling Lee to fight the Federals to a standstill. During the night, both armies consolidated their lines. In spite of crippling casualties, Lee continued to skirmish with McClellan throughout September 18, while removing his battered army south of the Potomac River.

McClellan successfully turned Lee's invasion back, making the battle a strategic Union victory. From a tactical standpoint, the battle was somewhat inconclusive; the Union Army successfully repelled the Confederate invasion, but suffered heavier casualties and failed to defeat Lee's army outright. President Abraham Lincoln, unhappy with McClellan's general pattern of overcaution and his failure to pursue the retreating Lee, relieved McClellan of command in November.

Nevertheless, the strategic accomplishment was a significant turning point in the war in favor of the Union due in large part to its political ramifications: the battle's result gave Lincoln the political confidence to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. This effectively discouraged the British and French governments from recognizing the Confederacy, as neither power wished to give the appearance of supporting slavery.

Edited 7 d ago

Posted 7 d ago

Responses: 4

Posted 7 d ago

Here are some additional images (the Battle field at Antietam. Maryland) and a Memordum from the Secretary of War authorizing the award of the MOH to Assitant Surgeon Richard J. Curran.

(7)

Comment

(0)

Lt Col John (Jack) Christensen

6 d

I've walked that battlefield many times when in college. Girl I was dating was a history major concentrating on the Civil War and we hit every battlefield within a 300 mile radius of Roanoke.

(2)

Reply

(0)

Posted 7 d ago

Excellent MOH History of and for Assistant Surgeon (Highest Rank: Surgeon) Richard J. Curran, US Army, 33rd New York Infantry, Date of Action: 1862, Home Town: Ennis, Location of Action: The Battle of Antietam, Maryland.

(6)

Comment

(0)

Posted 7 d ago

What is a 1/4 Master? Btw, great series. MOH winners.

(6)

Comment

(0)

Read This Next

Medal of Honor

Medal of Honor Medals

Medals Civil War

Civil War Military History

Military History Heroes

Heroes