Posted on Sep 11, 2014

Lack of minority officers leading Army combat units? How do you respond to this article?

85.8K

562

309

17

15

2

WASHINGTON — Command of the Army's main combat units — its pipeline to top leadership — is virtually devoid of black officers, according to interviews, documents and data obtained by USA TODAY.

The lack of black officers who lead infantry, armor and field artillery battalions and brigades — there are no black colonels at the brigade level this year — threatens the Army's effectiveness, disconnects it from American society and deprives black officers of the principal route to top Army posts, according to officers and military sociologists. Fewer than 10 percent of the active-duty Army's officers are black compared with 18 percent of its enlisted men, according to the Army.

The problem is most acute in its main combat units: infantry, armor and artillery. In 2014, there was not a single black colonel among those 25 brigades, the Army's main fighting unit of about 4,000 soldiers. Brigades consist of three to four battalions of 800 to 1,000 soldiers led by lieutenant colonels. Just one of those 78 battalions is scheduled to be led by a black officer in 2015.

Leading combat units is an essential ticket to the Army's brass ring. Gen. Raymond Odierno, the Army's chief of staff, commanded artillery units; his predecessor, Gen. Martin Dempsey, led armored units, and is now the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

"The issue exists. The leadership is aware of it," says Brig. Gen. Ronald Lewis, the Army's chief of public affairs. Lewis is a helicopter pilot who has commanded at the battalion and brigade levels and is African-American. "The leadership does have an action plan in place. And it's complicated."

Among the complications: expanding the pool of minority candidates qualified to be officers, and helping them choose the right military jobs they'll need to climb the ranks, Lewis says.

To be sure, there are black officers who have attained four stars. Gen. Lloyd Austin, an infantry officer, leads Central Command, arguably the military's most critical combatant command as it oversees military operations in the Middle East. Another four-star officer, Gen. Vincent Brooks, leads U.S. Army Pacific, and Gen. Dennis Via runs Army Materiel Command, its logistics operation.

The concern, however, is for Army's seed bed for four-star officers — the combat commands from which two-thirds of its generals are grown. They're unlikely to produce a diverse officer corps if candidates remain mostly white.

"It certainly is a problem for several reasons," says Col. Irving Smith, director of sociology at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Smith is also an African-American infantry officer who has served in Afghanistan. "First we are a public institution. And as a public institution we certainly have more of a responsibility to our nation than a private company to reflect it. In order to maintain their trust and confidence, the people of America need to know that the Army is not only effective but representative of them."

Black officers at the top ranks of the brass show young minority officers what they can achieve. Their presence also signals to allies in emerging democracies like Afghanistan that inclusive leadership is important. Diverse leadership, research shows, is better able to solve complex problems such as those the Army confronted in Iraq and Afghanistan, Smith said.

"It comes down to effectiveness," Smith said. "Diversity and equal opportunity are important, but most people don't point out that it makes the Army more effective."

The Problem

The Army's — and the Pentagon's — main ground fighting force remains the Army's infantry, armor and artillery units, although aviation and engineering units are also considered combat arms. Many of their names have become familiar to the American public after more than a decade of war: The 101st Airborne Division; the 82nd Airborne Division; the 10th Mountain Division.

They share a proud history of tough fights and multiple deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. They also share a lack of black leaders. In all, eight of 10 of the Army's fighting divisions do not have a black battalion commander in their combat units.

(For now, they also lack women. The military plans to open combat roles to women in 2016.)

USA TODAY obtained the Army's list of battalion and brigade commanders. Several officers familiar with the personnel on them identified the black officers, which the Army refused to do. The paper considered officers in infantry, armor and field artillery — the three main combat-arms branches.

The results: In 2014, there is not a single black commander among its 25 brigades; there were three black commanders in its 80 battalion openings.

In 2015, there will be two black commanders of combat brigades; and one black commander among 78 battalions openings.

"It's command. If you don't command at the (lieutenant colonel) level, you're not going to command at (the colonel level)," says Army Col. Ron Clark, an African-American infantry officer who has commanded platoon, company, battalion and brigade level. "If you don't command at the (colonel) level, you're not going to be a general officer."

Capt. Grancis Santana, 33, knows about the long odds he faces as an artillery officer hoping to become a colonel.

He found few black officers in his specialty — about two of 20 when he was a lieutenant, and about three of 30 when he made captain.

"It's not a good feeling when you're one of the few," Santana said. "There was no discrimination; there are just not a lot of people like you."

A key reason is the paucity of black officers graduated by the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, its ROTC programs and Officer Candidate School.

For instance, the newly minted officer classes of 2012 and 2013 in combat arms remained mostly white, according to data released by the Army. Of the 238 West Point graduates commissioned to be infantry officers in 2012, 199 were white; seven were black. At Officer Candidate School, which accepts qualified enlisted soldiers and graduates with four-year degrees, 66 received commissions as infantry officers — 55 were white, none was black. The figures remained nearly unchanged for 2013.

The downsizing of the Army is having a disproportional effect on African-American officers. From the pool of officers screened, almost 10 percent of eligible black majors are being dismissed from the Army compared with 5.6 percent of eligible white majors, USA TODAY reported in early August. The Army is cutting 550 majors and about 1,000 captains as the Army seeks to reduce its force to 490,000 soldiers by the end of 2015.

The Causes

Two forces seem to reinforce the lack of black officers in combat command. For decades, young black men have tended to choose other fields, including logistics. With fewer role models and mentors in combat specialties, those fields have been seen as less welcoming to African-American officers.

Irving Smith remembers his parents being "heartbroken" that he chose infantry.

"African Americans have historically used the armed forces as a means of social mobility," says Smith, who joined the infantry, has risen to the rank of colonel and now is professor and director of sociology at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. "That is certainly true for African Americans who have used the armed forces as a bridging opportunity (to new careers)."

Parents, pastors and coaches of young black men and women considering the Army often don't encourage them to join the combat specialties.

"Why would you go in the infantry?" Smith says of a common question. "Why would you want to run around in the woods and jump out of airplanes, things that have no connection to private businesses? Do transportation. Do logistics. That will provide you with transferable skills."

Developing marketable skills has been a key motivation for many African Americans, said David Segal, a military sociologist at the University of Maryland. That has often meant driving a truck, not a tank.

"There has been a trend among African Americans who do come into the military to gravitate to career fields that have transfer value — that pretty much excludes the combat arms," Segal said.

Clark, who now works at the Pentagon, wasn't encouraged initially to join the infantry. His father enlisted in 1964 and had an Army career in food service.

"He grew up in a small town in southern Louisiana in the middle of Jim Crow South," Clark says. "He was tired of having someone telling him where to sit on a bus, which water fountain to drink from and which bathroom he could use."

At age 11, the younger Clark remembers climbing on a tank when the family was stationed in Grafenwoehr, Germany. The U.S. invasion of Grenada in 1983 sealed the deal for him: He wanted to be infantryman.

"I wanted to be an Airborne Ranger in a tree," Clark says, "and my dad was not having it. He said, 'Nope, you are not going following my footsteps. I want you to go to college.'"

The compromise, after his father had him speak with an African-American brigade executive officer named Larry Ellis, was to enroll at West Point. Ellis went on to become a four-star general, and Clark graduated from the academy in 1988.

Clark and Irving remain exceptional cases.

The downsizing of the Army is having a disproportional effect on African-American officers. From the pool of officers screened, almost 10 percent of eligible black majors are being dismissed from the Army compared with 5.6 percent of eligible white majors, USA TODAY reported in early August. The Army is cutting 550 majors and about 1,000 captains as the Army seeks to reduce its force to 490,000 soldiers by the end of 2015.

The Army's Response

The problem has attracted attention at the Army's highest ranks. In March, Army Secretary John McHugh and Odierno, the chief of staff, issued a directive aimed at diversifying the leadership of its combat units.

USA TODAY obtained a copy of the memo, which notes that the Army historically has drawn the majority of its generals from combat fields, specifically "Infantry, Armor and Field Artillery." For at least two decades, however, young minority officers have selected those fields in the numbers necessary to produce enough generals.

"African Americans have the most limited preference in combat arms, followed by Hispanic and Asian Pacific officers," the memo states. While black officers make up 12 percent of Army officers in all competitive specialties, they make up just 7 percent of the Army's infantry, armor and artillery officers. For junior officers, that figure is lower, 6 percent.

Minority groups need a "critical mass" of about 15 percent to feel they have a voice, Smith says.

The Army's plan calls for enhanced recruiting and mentoring for minority officers, particularly in combat fields, tracking their progress and encouraging mentorship.

Mentors needn't be of the same race, Clark and Lewis say. Lewis noted that several of his closest mentors were white officers, including retired general Richard Cody, who retired as Army vice chief of staff. Cody advised him to spend time at the Army's National Training Center, in the California desert. It paid off, Lewis says.

"Everyone does not have to look like you," Lewis says. "You have to be able to receive mentorship, leadership. And you have to follow some of that. You may have to spend some time at a really hard place for a bit."

Byron Bagby, a retired African-American two-star artillery officer, applauds the Army for acknowledging the problem and taking steps to address it. He cautions progress will be slow. Bagby retired in 2011 from a top post with NATO in the Netherlands.

"We're not going to solve this tomorrow, or a year from now," Bagby says.

Smith has another suggestion for the Army. Ask an in-house expert: him.

The brass could also stop by his office for a chat, he says.

"I've never had anybody from the Department of the Army come to me. I'm a sociologist. I've studied these issues for six years."

The lack of black officers who lead infantry, armor and field artillery battalions and brigades — there are no black colonels at the brigade level this year — threatens the Army's effectiveness, disconnects it from American society and deprives black officers of the principal route to top Army posts, according to officers and military sociologists. Fewer than 10 percent of the active-duty Army's officers are black compared with 18 percent of its enlisted men, according to the Army.

The problem is most acute in its main combat units: infantry, armor and artillery. In 2014, there was not a single black colonel among those 25 brigades, the Army's main fighting unit of about 4,000 soldiers. Brigades consist of three to four battalions of 800 to 1,000 soldiers led by lieutenant colonels. Just one of those 78 battalions is scheduled to be led by a black officer in 2015.

Leading combat units is an essential ticket to the Army's brass ring. Gen. Raymond Odierno, the Army's chief of staff, commanded artillery units; his predecessor, Gen. Martin Dempsey, led armored units, and is now the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

"The issue exists. The leadership is aware of it," says Brig. Gen. Ronald Lewis, the Army's chief of public affairs. Lewis is a helicopter pilot who has commanded at the battalion and brigade levels and is African-American. "The leadership does have an action plan in place. And it's complicated."

Among the complications: expanding the pool of minority candidates qualified to be officers, and helping them choose the right military jobs they'll need to climb the ranks, Lewis says.

To be sure, there are black officers who have attained four stars. Gen. Lloyd Austin, an infantry officer, leads Central Command, arguably the military's most critical combatant command as it oversees military operations in the Middle East. Another four-star officer, Gen. Vincent Brooks, leads U.S. Army Pacific, and Gen. Dennis Via runs Army Materiel Command, its logistics operation.

The concern, however, is for Army's seed bed for four-star officers — the combat commands from which two-thirds of its generals are grown. They're unlikely to produce a diverse officer corps if candidates remain mostly white.

"It certainly is a problem for several reasons," says Col. Irving Smith, director of sociology at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Smith is also an African-American infantry officer who has served in Afghanistan. "First we are a public institution. And as a public institution we certainly have more of a responsibility to our nation than a private company to reflect it. In order to maintain their trust and confidence, the people of America need to know that the Army is not only effective but representative of them."

Black officers at the top ranks of the brass show young minority officers what they can achieve. Their presence also signals to allies in emerging democracies like Afghanistan that inclusive leadership is important. Diverse leadership, research shows, is better able to solve complex problems such as those the Army confronted in Iraq and Afghanistan, Smith said.

"It comes down to effectiveness," Smith said. "Diversity and equal opportunity are important, but most people don't point out that it makes the Army more effective."

The Problem

The Army's — and the Pentagon's — main ground fighting force remains the Army's infantry, armor and artillery units, although aviation and engineering units are also considered combat arms. Many of their names have become familiar to the American public after more than a decade of war: The 101st Airborne Division; the 82nd Airborne Division; the 10th Mountain Division.

They share a proud history of tough fights and multiple deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. They also share a lack of black leaders. In all, eight of 10 of the Army's fighting divisions do not have a black battalion commander in their combat units.

(For now, they also lack women. The military plans to open combat roles to women in 2016.)

USA TODAY obtained the Army's list of battalion and brigade commanders. Several officers familiar with the personnel on them identified the black officers, which the Army refused to do. The paper considered officers in infantry, armor and field artillery — the three main combat-arms branches.

The results: In 2014, there is not a single black commander among its 25 brigades; there were three black commanders in its 80 battalion openings.

In 2015, there will be two black commanders of combat brigades; and one black commander among 78 battalions openings.

"It's command. If you don't command at the (lieutenant colonel) level, you're not going to command at (the colonel level)," says Army Col. Ron Clark, an African-American infantry officer who has commanded platoon, company, battalion and brigade level. "If you don't command at the (colonel) level, you're not going to be a general officer."

Capt. Grancis Santana, 33, knows about the long odds he faces as an artillery officer hoping to become a colonel.

He found few black officers in his specialty — about two of 20 when he was a lieutenant, and about three of 30 when he made captain.

"It's not a good feeling when you're one of the few," Santana said. "There was no discrimination; there are just not a lot of people like you."

A key reason is the paucity of black officers graduated by the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, its ROTC programs and Officer Candidate School.

For instance, the newly minted officer classes of 2012 and 2013 in combat arms remained mostly white, according to data released by the Army. Of the 238 West Point graduates commissioned to be infantry officers in 2012, 199 were white; seven were black. At Officer Candidate School, which accepts qualified enlisted soldiers and graduates with four-year degrees, 66 received commissions as infantry officers — 55 were white, none was black. The figures remained nearly unchanged for 2013.

The downsizing of the Army is having a disproportional effect on African-American officers. From the pool of officers screened, almost 10 percent of eligible black majors are being dismissed from the Army compared with 5.6 percent of eligible white majors, USA TODAY reported in early August. The Army is cutting 550 majors and about 1,000 captains as the Army seeks to reduce its force to 490,000 soldiers by the end of 2015.

The Causes

Two forces seem to reinforce the lack of black officers in combat command. For decades, young black men have tended to choose other fields, including logistics. With fewer role models and mentors in combat specialties, those fields have been seen as less welcoming to African-American officers.

Irving Smith remembers his parents being "heartbroken" that he chose infantry.

"African Americans have historically used the armed forces as a means of social mobility," says Smith, who joined the infantry, has risen to the rank of colonel and now is professor and director of sociology at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. "That is certainly true for African Americans who have used the armed forces as a bridging opportunity (to new careers)."

Parents, pastors and coaches of young black men and women considering the Army often don't encourage them to join the combat specialties.

"Why would you go in the infantry?" Smith says of a common question. "Why would you want to run around in the woods and jump out of airplanes, things that have no connection to private businesses? Do transportation. Do logistics. That will provide you with transferable skills."

Developing marketable skills has been a key motivation for many African Americans, said David Segal, a military sociologist at the University of Maryland. That has often meant driving a truck, not a tank.

"There has been a trend among African Americans who do come into the military to gravitate to career fields that have transfer value — that pretty much excludes the combat arms," Segal said.

Clark, who now works at the Pentagon, wasn't encouraged initially to join the infantry. His father enlisted in 1964 and had an Army career in food service.

"He grew up in a small town in southern Louisiana in the middle of Jim Crow South," Clark says. "He was tired of having someone telling him where to sit on a bus, which water fountain to drink from and which bathroom he could use."

At age 11, the younger Clark remembers climbing on a tank when the family was stationed in Grafenwoehr, Germany. The U.S. invasion of Grenada in 1983 sealed the deal for him: He wanted to be infantryman.

"I wanted to be an Airborne Ranger in a tree," Clark says, "and my dad was not having it. He said, 'Nope, you are not going following my footsteps. I want you to go to college.'"

The compromise, after his father had him speak with an African-American brigade executive officer named Larry Ellis, was to enroll at West Point. Ellis went on to become a four-star general, and Clark graduated from the academy in 1988.

Clark and Irving remain exceptional cases.

The downsizing of the Army is having a disproportional effect on African-American officers. From the pool of officers screened, almost 10 percent of eligible black majors are being dismissed from the Army compared with 5.6 percent of eligible white majors, USA TODAY reported in early August. The Army is cutting 550 majors and about 1,000 captains as the Army seeks to reduce its force to 490,000 soldiers by the end of 2015.

The Army's Response

The problem has attracted attention at the Army's highest ranks. In March, Army Secretary John McHugh and Odierno, the chief of staff, issued a directive aimed at diversifying the leadership of its combat units.

USA TODAY obtained a copy of the memo, which notes that the Army historically has drawn the majority of its generals from combat fields, specifically "Infantry, Armor and Field Artillery." For at least two decades, however, young minority officers have selected those fields in the numbers necessary to produce enough generals.

"African Americans have the most limited preference in combat arms, followed by Hispanic and Asian Pacific officers," the memo states. While black officers make up 12 percent of Army officers in all competitive specialties, they make up just 7 percent of the Army's infantry, armor and artillery officers. For junior officers, that figure is lower, 6 percent.

Minority groups need a "critical mass" of about 15 percent to feel they have a voice, Smith says.

The Army's plan calls for enhanced recruiting and mentoring for minority officers, particularly in combat fields, tracking their progress and encouraging mentorship.

Mentors needn't be of the same race, Clark and Lewis say. Lewis noted that several of his closest mentors were white officers, including retired general Richard Cody, who retired as Army vice chief of staff. Cody advised him to spend time at the Army's National Training Center, in the California desert. It paid off, Lewis says.

"Everyone does not have to look like you," Lewis says. "You have to be able to receive mentorship, leadership. And you have to follow some of that. You may have to spend some time at a really hard place for a bit."

Byron Bagby, a retired African-American two-star artillery officer, applauds the Army for acknowledging the problem and taking steps to address it. He cautions progress will be slow. Bagby retired in 2011 from a top post with NATO in the Netherlands.

"We're not going to solve this tomorrow, or a year from now," Bagby says.

Smith has another suggestion for the Army. Ask an in-house expert: him.

The brass could also stop by his office for a chat, he says.

"I've never had anybody from the Department of the Army come to me. I'm a sociologist. I've studied these issues for six years."

Posted >1 y ago

Responses: 104

If only 10 percent of Army officers are black then it would seem by statistics alone that you wouldn't find a lot of Black officers the further up you go. If 90 percent of officers are name Steve and ten percent are named George, then by odds alone you would find a lot more Steves sticking around. We should be looking for good leadership and not be racist about what color they are. If their is a EO promotion problem it should be adressed.

The question should be is, why are Blacks not seeing the officer route a feasibleone?

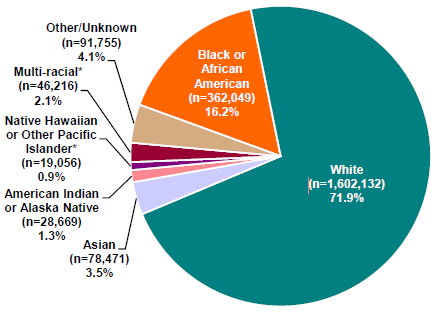

2012 Militaryonesource DOD Demographics:

http://www.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2012_Demographics_Report.pdf

The question should be is, why are Blacks not seeing the officer route a feasibleone?

2012 Militaryonesource DOD Demographics:

http://www.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2012_Demographics_Report.pdf

(3)

(0)

CPT Ahmed Faried

There is definitely some good old boy shit going on though and I know this from personal experience. I've had one shitty Company Commander my entire time in the military. He was a ring knocker type and treated the other ring knockers differently. He and I just didn't get along. He tried to intentionally sabotage me on training missions and when I refused a stupid/incorrect order we got into a shouting match. Long story short it was a battalion-wide exercise. I had finished setting up my weapons squad as support by fire and was leading my remaining three squads into the assault position. I reach a LDA with no cover, just open ground. I decide to backtrack and go a mile further down where I could cross over a path that had more cover. The CDR gets on me for taking too long. I tell him that in a real-world scenario I wouldn't cross that LDA so why do it in practice. He didn't like that answer and we got into it. He tried to get me fired but when we had the BN Cdr come validate the following week, I was one of two Lieutenants who wasn't re-assigned (i.e fired). Every other commander I've worked with since that shit-stain has loved me. So although this is my personal experience I wonder if it is much larger than me and perhaps could be the reason that the higher you go the less minority officers you see in the combat arms.

(3)

(0)

Capt Jeff S.

Did the "Good ol' Boys Club" stop Colin Powell from becoming Chairman of the JCS? If you are good at what you do >>AND PROFESSIONAL,<< nothing will stop you from moving up the ranks... except a self-inflicted wound.

I'd be careful about referring to my Company Commander in the manner you did [-- especially with that SM next to your name.] You showed good judgment on the Exercise but poor judgment on your post. I gave you the Up Vote anyway, because I can relate, but you need to rethink what you said and ask yourself, "Is there a better way to say that?" Wouldn't want to see a promising career cut short due to lack of judgment. [Hint: You may want to fix that.]

I'd be careful about referring to my Company Commander in the manner you did [-- especially with that SM next to your name.] You showed good judgment on the Exercise but poor judgment on your post. I gave you the Up Vote anyway, because I can relate, but you need to rethink what you said and ask yourself, "Is there a better way to say that?" Wouldn't want to see a promising career cut short due to lack of judgment. [Hint: You may want to fix that.]

(0)

(0)

Here we go again. WorldNetDaily published this story this morning about a West Point Professor saying the Army is "too white." I don't think it makes any bit of difference. I maintain that everyone in the Army is green and that color is irrelevant. But these stories persist in coming out.

I don't think it matters what color an officer is. The main question is can that person lead the Troops? Can that person fit and win the Nation's wars? Color is irrelevant in that respect.

I don't think it matters what color an officer is. The main question is can that person lead the Troops? Can that person fit and win the Nation's wars? Color is irrelevant in that respect.

(2)

(0)

Combat knows no color race nationality or religion. Only the best should lead men into combat. Political correctness will get you killed every time.

(2)

(0)

I may be simplifying this, but aren't we part of an all volunteer force? If we are part of an all volunteer force, then aren't any demographics collected going to be "skewed" by the fact that it is an all volunteer population? And if the demographics collected are "skewed" because we are part of an all volunteer force, then connecting the dots or lines between color/race/creed/etc would be irrelevant because we are part of an all volunteer force?

"Skewed" is not be the right adjective to use here, but yinz guys get my drift, right?

"Skewed" is not be the right adjective to use here, but yinz guys get my drift, right?

(2)

(0)

I actually feel offended by this article. I thought we had moved beyond racism in this country (or at least in the Army) with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the "I have a dream speech." The whole premise was to judge people based on the content of their character, not the color of their skin. I believe I've been true to that.

From what I've heard about the boards is that they are quite diverse and no one person can influence the whole group. That tells me that even if there was a racist person on the board (promotion or separation) that there would not be a way for that person to really inject his/her racist views into the board process.

I read the article below about the Chief of Staff saying that a lack of black officers in the combat arms is a problem and that they were disproportionately cut by the separation board. As much as I disagree with the manner in which that board was conducted, I cannot believe that the board made racist decisions. I believe the Chief of Staff is searching for a problem that doesn't necessarily exist. I think the separation board looked at the content of every officer's record (for up to 60 seconds) and made a decision. I don't think it was based on skin color. If it was, then the problem lays with the board process.

Yes, diversity in the ranks is good - it brings different viewpoints and different methods to achieving results. It also reflects the diversity of the country.

Was the board racist? I highly doubt it. The board would have to consist of one type of people for that to happen, and I don't think that's likely in the current board process.

Is there a way to bring more diversity into the combat arms branches? This will be based on the recruiters and the interest of the candidates - and, of course, the commissioning board (needs of the Army).

While I am on the "soapbox," I think a better way of conducting these boards is by MOS. 11A competes against 11A, 25A competes against 25A, and so on. That way the Army can be assured that the right number of a particular MOS is getting promoted or separated. I think the way it works now is all combat arms is competing against each other, but that leads to the possibility of promoting too many of one MOS at the expense of another.

Sorry for ranting, but when I read that article I had all those thoughts I felt should be expressed somehow. In short, I don't think the boards are racist, and I don't think the Army as a whole is racist. There may be some pockets here and there, but I don't see how the boards can be compromised in that way. I think the collection of racial statistics in boards is a problem if the results are based on the content of the records. Collecting racial/gender statistics opens the door for affirmative action which I don't think is needed in today's Army. I think the Army is more fair than any other organization on Earth.

From what I've heard about the boards is that they are quite diverse and no one person can influence the whole group. That tells me that even if there was a racist person on the board (promotion or separation) that there would not be a way for that person to really inject his/her racist views into the board process.

I read the article below about the Chief of Staff saying that a lack of black officers in the combat arms is a problem and that they were disproportionately cut by the separation board. As much as I disagree with the manner in which that board was conducted, I cannot believe that the board made racist decisions. I believe the Chief of Staff is searching for a problem that doesn't necessarily exist. I think the separation board looked at the content of every officer's record (for up to 60 seconds) and made a decision. I don't think it was based on skin color. If it was, then the problem lays with the board process.

Yes, diversity in the ranks is good - it brings different viewpoints and different methods to achieving results. It also reflects the diversity of the country.

Was the board racist? I highly doubt it. The board would have to consist of one type of people for that to happen, and I don't think that's likely in the current board process.

Is there a way to bring more diversity into the combat arms branches? This will be based on the recruiters and the interest of the candidates - and, of course, the commissioning board (needs of the Army).

While I am on the "soapbox," I think a better way of conducting these boards is by MOS. 11A competes against 11A, 25A competes against 25A, and so on. That way the Army can be assured that the right number of a particular MOS is getting promoted or separated. I think the way it works now is all combat arms is competing against each other, but that leads to the possibility of promoting too many of one MOS at the expense of another.

Sorry for ranting, but when I read that article I had all those thoughts I felt should be expressed somehow. In short, I don't think the boards are racist, and I don't think the Army as a whole is racist. There may be some pockets here and there, but I don't see how the boards can be compromised in that way. I think the collection of racial statistics in boards is a problem if the results are based on the content of the records. Collecting racial/gender statistics opens the door for affirmative action which I don't think is needed in today's Army. I think the Army is more fair than any other organization on Earth.

(2)

(0)

The headline refers to minority officers but the story itself refers to black officers. There is an advantage within combat arms and getting promoted to the highest ranks. There is also an advantage in choosing non combat arms fields in that the experience applies more to civilian career applications. There is also the advantage that deployments may be less frequent and more comfortable. I don't see any disadvantage for the Army because there is no problem finding willing and effective leaders.

There are cultural differences between the races and the sexes. I don't believe these cultural differences and tendencies should be viewed as problems. We have the most effective fighting forces when everyone finds the niche they fit best and are assigned accordingly.

There are cultural differences between the races and the sexes. I don't believe these cultural differences and tendencies should be viewed as problems. We have the most effective fighting forces when everyone finds the niche they fit best and are assigned accordingly.

(2)

(0)

Maybe we should look at professional sports like basketball and football and force more diversity, regardless of what positions people sign up for or their actual ability.

The military has led the charge on many fronts and EO is no exception. So much so that major corporations have looked at the military model as the standard to follow.

The same people that write the article insinuating some type of racial bias are the same ones who accused the military of sending all the minorities to the front lines during OIF I. All false and all in the effort to stir the pot for an agenda not for real progress.

The military has led the charge on many fronts and EO is no exception. So much so that major corporations have looked at the military model as the standard to follow.

The same people that write the article insinuating some type of racial bias are the same ones who accused the military of sending all the minorities to the front lines during OIF I. All false and all in the effort to stir the pot for an agenda not for real progress.

(2)

(0)

As long as we keep bringing attention to ethnic divides, there will be ethnic divides. Quickest way in my opinion to get rid of views like that would be to just stop talking about it. I'm not saying that if someone legitimately does or says something racist that they shouldn't be dealt with. I'm merely saying that we shouldn't keep giving undue attention to topics that don't have any significant meaning.

(2)

(0)

SPC Randy Torgerson

I agree completely. I think after 50 years of talking about it, well its probably enough. Will there always be racist? Of course, and it goes both ways. In fact I would say the number one reason we're still talking about it is because there are so many minority's who are racist or just have it in their head that their still being picked on.

Each of us should examine who are friends and acquaintances are... I have only had one good friend who was racist in my life, plus one co-worker. I didn't associate myself with the co-worker once I discovered his behavior with my own eyes. But guess what? He was fired from the police force within months of that incident. As far as my good friend goes, he's a black FBI agent and I'm still trying to correct him. People should be evaluated individually. Are there some African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Jewish Americans, Japanese Americans, white Americans that I don't like? You betcha.... But not for those racial reasons.

Each of us should examine who are friends and acquaintances are... I have only had one good friend who was racist in my life, plus one co-worker. I didn't associate myself with the co-worker once I discovered his behavior with my own eyes. But guess what? He was fired from the police force within months of that incident. As far as my good friend goes, he's a black FBI agent and I'm still trying to correct him. People should be evaluated individually. Are there some African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Jewish Americans, Japanese Americans, white Americans that I don't like? You betcha.... But not for those racial reasons.

(1)

(0)

For me I see a lot of change, "The more things change, the more they stay the same" SFC Drake, your serving for 28yrs in America's Army, I thank you, I started back in 1971 put out at 60, 2012. 40yrs. In the 70" we had two America's service, all were the same. It was White and minority's. [plus bed wetter, Donald Duck (Navy), Girl scout, Passion fruit & fairy. we were all train to hate them.] Ask a Marine how many types of Marines are there? (Dark & light) The Army Air Corps minority officers Most stated were the best. Let's get back to making the future, It should be change for the better, not the color, who rich or rank, but for all.

(2)

(0)

SFC A.M. Drake

I concur...but I have to admit....I think it goes in flows and ebbs meaning the percentages of officers in each AOC

(0)

(0)

I wonder why the author chose to focus on Combat Arms. Combat Arms is not for everyone, enlisted or officer. If the author wanted to take a look at what I think would be a more interesting issue, it would be why is the Army percentage of minority officers more than double that of the other services (except the Navy, the Army has 4% more minority officers than the Navy).

Not saying that the issue may need to be looked at, in 2013 the Army did decrease in total minority officers by 1%, from 27% to 26% overall.

In looking at grades O7 thru O-10, Army 13.4%, Navy 8.10%, USMC 12.4, USAF 5.9%. Why shouldn't the disparity between the Navy/AF to USA/USMC be more of an issue. Why did he select the issue of Army-Combat Arms.

If Officers want to go Combat Arms, they have to work hard enough in the USMA, OCS, ROTC, etc to earn their top choices. Lets not base their decisions on their race, lets base it on their desire to be all they want to be.

Let's not create an issue where the Army will try to fix a problem that just may not be a problem. WE have to many un-fixed issues out there already.

I'm no genius or statistical rocket scientist, however, I know Soldiers. So, I hope the real concern will be in keeping the best/most qualified Officers leading Soldiers, Bn, Bde, Div, etc and not create some quota system that does otherwise. Soldiers could care less what race or nationality "Good" Leaders are! And Rightly so!

Not saying that the issue may need to be looked at, in 2013 the Army did decrease in total minority officers by 1%, from 27% to 26% overall.

In looking at grades O7 thru O-10, Army 13.4%, Navy 8.10%, USMC 12.4, USAF 5.9%. Why shouldn't the disparity between the Navy/AF to USA/USMC be more of an issue. Why did he select the issue of Army-Combat Arms.

If Officers want to go Combat Arms, they have to work hard enough in the USMA, OCS, ROTC, etc to earn their top choices. Lets not base their decisions on their race, lets base it on their desire to be all they want to be.

Let's not create an issue where the Army will try to fix a problem that just may not be a problem. WE have to many un-fixed issues out there already.

I'm no genius or statistical rocket scientist, however, I know Soldiers. So, I hope the real concern will be in keeping the best/most qualified Officers leading Soldiers, Bn, Bde, Div, etc and not create some quota system that does otherwise. Soldiers could care less what race or nationality "Good" Leaders are! And Rightly so!

(2)

(0)

Read This Next

Officers

Officers Diversity

Diversity