Responses: 7

Petain: The Pessimistic Patriot

Prof John Derry talks about Philippe Pétain, the French general who is widely acknowledged as having saved the French Army in 1917. Petain was sidelined in 1...

Thank you, my friend SGT (Join to see) for reminding us that on July 11, 1940, Marshall Philippe Henri Petain became head of the collaborative Vichy government of France.

Petain: The Pessimistic Patriot

"Prof John Derry talks about Philippe Pétain, the French general who is widely acknowledged as having saved the French Army in 1917. Petain was sidelined in 1918, and in 1940 surrendered to the Nazis. Is his reputation deserved or was he a 'pessimistic patriot'?"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uIUiTkrJI68

Images

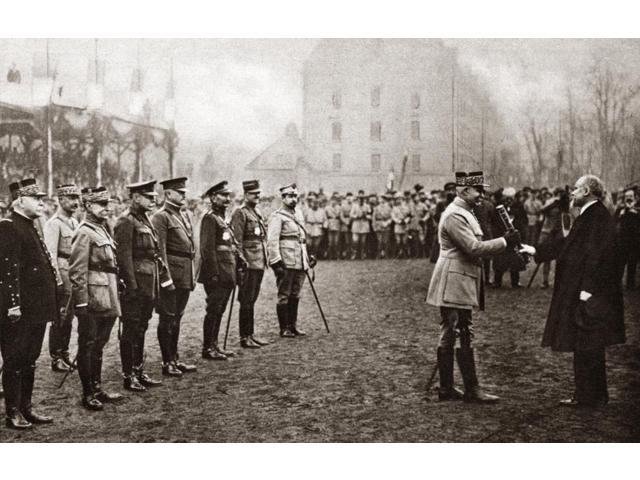

1. 1918 General Henri Petain being presented with the Marshal's Baton.

2. October 24th 1940 at Montoire, Leader of Vichy France, Marshal Philippe Henri Pétain meeting German leader Adolf Hitler.

3. Le Fort de Pierre-Levée holding celebrated prisoner Marshall Philippe Henri Petain (Yoann Roignant).

4. 1949 Marshall Philippe Henri Petain accompanied by his doctor Albert Massonie Fort de Pierre Levée, on the Île d'Yeu.jpg

Background from

Three sources:

[1] & [2] spartacus-educational.com/FWWpetain.htm

[3] bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/petain_philippe.shtml

[4] thebiography.us/en/petain-henri-philippe-benomi-omer

"Henri-Philippe Petain was born in Cauch-a-la-Tour in 1856. He was born in Couchy-à-la-Tour in 1856, into a family of peasants." [4]

He completed primary studies [and] choose the military career and enters the Military Academy.

"He joined the French Army in 1876 and attending the St Cyr Military School and spent many years as an infantry officer and an army instructor. After studying the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05)

Petain became convinced that the increased fire-power of modern weapons strongly favoured the defensive. Others in the French Army, for example, Ferdinand Foch, believed the opposite to be true.

On the outbreak of the First World War Petain was due to retire from the army. Instead he was promoted to brigadier and took part in the Artois Offensive. In 1915 Joseph Joffre sent Petain to command the French troops at Verdun. Afterwards Petain was praised for his artillery-based defensive operations and his organisation of manpower resources.

After the disastrous Nivelle Offensive in the spring of 1917, the French Army suffered widespread mutinies on the Western Front. Petain replaced Robert Nivelle as Commander-in-Chief. This was a popular choice as Petain, unlike Nivelle, had a reputation for having a deep concern for the lives of his soldiers. By improving the living conditions of the soldiers at the front and restricting the French Army to defensive operations, Petain gradually improved the morale of his troops." [1]

"After a number of World War One commands, in 1916, Pétain was ordered to stop the massive German attack on the city of Verdun. He reorganised the front lines and transport systems and was able to inspire his troops, turning a near-hopeless situation into a successful defence. He became a popular hero and replaced General Robert Nivelle as commander-in-chief of the French army. Pétain then successfully re-established discipline after a series of mutinies by explaining his intentions to the soldiers personally and improving their living conditions. In November 1918, he was made a marshal of France.

In 1934, Pétain was appointed minister of war, and then secretary of state in the following year. In 1939, he was appointed French ambassador to Spain. In May 1940, with France under attack from Germany, Pétain was appointed vice premier. In June he asked for an armistice, upon which he was appointed 'chief of state', enjoying almost absolute powers. The armistice gave the Germans control over the north and west of France, including Paris, but left the remainder as a separate regime under Pétain, with its capital at Vichy. Officially neutral, in practice the regime collaborated closely with Germany, and brought in its own anti-Semitic legislation."

In December 1940, Pétain dismissed his vice-premier, Pierre Laval, for his policy of close Franco-German collaboration. But Laval's successors were unacceptable to the Germans and Laval was restored. In November 1942, in response to allied landings in North Africa, the Germans invaded the unoccupied zone of France. Vichy France remained nominally in existence, but Pétain became nothing more than a figurehead. In the summer of 1944, after the allied landings in France, Pétain was taken to Germany." [3]

Henri-Philippe Petain was tried and sentenced to death for collaborating with Germany on August 15, 1945, with the loss of all civil rights and confiscation of their property. However, the Court itself, given his advanced age, proposed to replace him the death penalty by the imprisonment.

General De Gaulle, head of the provisional Government, accepted the proposal that his death sentence to be commuted to life imprisonment and Pétain was transferred to the fortress of Portalet, located in the Pyrenees, to serve his sentence. Later, he was taken to Fort de Pierre Levée, on the Île d'Yeu off the Atlantic coast where Henri-Philippe Petain died on 23 July 1951.

[2] Background on meeting between Marshall Henri-Philippe Petain, General Weygand and Winston Churchill

"Paul Reynaud received us, firm and courteous despite the strain. We soon got down to discussion across the dining-room table; Petain, Reynaud, Weygand facing Churchill, Dill and me, with interpreters. General Georges joined us later. We talked for almost three hours, the discussion hardly advancing matters. The speakers were polite and correct, but although at that time the Maginot Line had not been attacked, it was soon evident that our French hosts had no hope.

Early in our talks, Weygand described the military situation, explaining how he had attempted to block a number of gaps in the line. He believed he had succeeded and, for the moment, the line held, but he had no more reserves. Somebody asked what would happen if another breach were made. 'No further military action will then be possible,' Weygand replied. Reynaud at once intervened sharply: 'That would be a political decision, Monsieur Ie General.' Weygand bowed and said: 'Certainly.' Georges told us that the French had altogether only some one hundred and ninety-five fighter aircraft left on the northern front.

Despite all the difficulties, our dinner, though simple, was admirably cooked and served. Reynaud presided, with Churchill on his right, Weygand sat opposite and I on his right. As we were taking our places, a tall and somewhat angular figure in uniform walked by on my side of the table. This was General Charles de Gaulle, Under-Secretary for Defence, whom I had met only once before. Weygand invited him pleasantly to take a place on his left. De Gaulle replied, curtly as I thought, that he had instructions to sit next to the British Prime Minister. Weygand flushed up, but made no comment, and so the meal began.

I had Marshal Petain on my other side. Conversation was not easy. His refrain was the destruction of France and the daily devastation of her cities, of which he mentioned several by name. I was sympathetic, but added that there were even worse fates than the destruction of cities. Petain rejoined that it was all very well for Britain to say that, we did not have the war in our country. When I said that we might have, I received an incredulous grunt in reply.

With General Weygand my talk was perfectly friendly and consisted mainly of a discussion about our available forces in Britain and what we were doing to speed their training. I had little cheer to give him. Weygand was something of an enigma. He had a famous reputation, crowned by his victory with Pilsudski over the Bolshevik forces in 1920. I had met him on several occasions, most recently early that year in the Middle East, and always found him friendly, quick and receptive, a modest man carrying his fame without affectation or conceit. He worked well with General Wavell, for the two men understood each other. I was glad when I heard that he had been called back to France to take over the supreme command. He achieved little, but probably no man could. At this stage, though always correct and courteous, he gave the impression of resigned fatalism. He was certainly not a man to fight the last desperate comer."

FYI COL Mikel J. Burroughs LTC Greg Henning MSgt Robert C Aldi CMSgt (Join to see) PVT Mark Zehner Lt Col Charlie Brown] SGT John " Mac " McConnell SP5 Mark Kuzinski PO1 H Gene Lawrence PO2 Kevin Parker PO3 Bob McCord LTC Jeff Shearer SGT Philip Roncari PO3 Phyllis Maynard CWO3 Dennis M. SFC William Farrell TSgt Joe C. SGT Carl Blas

Petain: The Pessimistic Patriot

"Prof John Derry talks about Philippe Pétain, the French general who is widely acknowledged as having saved the French Army in 1917. Petain was sidelined in 1918, and in 1940 surrendered to the Nazis. Is his reputation deserved or was he a 'pessimistic patriot'?"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uIUiTkrJI68

Images

1. 1918 General Henri Petain being presented with the Marshal's Baton.

2. October 24th 1940 at Montoire, Leader of Vichy France, Marshal Philippe Henri Pétain meeting German leader Adolf Hitler.

3. Le Fort de Pierre-Levée holding celebrated prisoner Marshall Philippe Henri Petain (Yoann Roignant).

4. 1949 Marshall Philippe Henri Petain accompanied by his doctor Albert Massonie Fort de Pierre Levée, on the Île d'Yeu.jpg

Background from

Three sources:

[1] & [2] spartacus-educational.com/FWWpetain.htm

[3] bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/petain_philippe.shtml

[4] thebiography.us/en/petain-henri-philippe-benomi-omer

"Henri-Philippe Petain was born in Cauch-a-la-Tour in 1856. He was born in Couchy-à-la-Tour in 1856, into a family of peasants." [4]

He completed primary studies [and] choose the military career and enters the Military Academy.

"He joined the French Army in 1876 and attending the St Cyr Military School and spent many years as an infantry officer and an army instructor. After studying the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05)

Petain became convinced that the increased fire-power of modern weapons strongly favoured the defensive. Others in the French Army, for example, Ferdinand Foch, believed the opposite to be true.

On the outbreak of the First World War Petain was due to retire from the army. Instead he was promoted to brigadier and took part in the Artois Offensive. In 1915 Joseph Joffre sent Petain to command the French troops at Verdun. Afterwards Petain was praised for his artillery-based defensive operations and his organisation of manpower resources.

After the disastrous Nivelle Offensive in the spring of 1917, the French Army suffered widespread mutinies on the Western Front. Petain replaced Robert Nivelle as Commander-in-Chief. This was a popular choice as Petain, unlike Nivelle, had a reputation for having a deep concern for the lives of his soldiers. By improving the living conditions of the soldiers at the front and restricting the French Army to defensive operations, Petain gradually improved the morale of his troops." [1]

"After a number of World War One commands, in 1916, Pétain was ordered to stop the massive German attack on the city of Verdun. He reorganised the front lines and transport systems and was able to inspire his troops, turning a near-hopeless situation into a successful defence. He became a popular hero and replaced General Robert Nivelle as commander-in-chief of the French army. Pétain then successfully re-established discipline after a series of mutinies by explaining his intentions to the soldiers personally and improving their living conditions. In November 1918, he was made a marshal of France.

In 1934, Pétain was appointed minister of war, and then secretary of state in the following year. In 1939, he was appointed French ambassador to Spain. In May 1940, with France under attack from Germany, Pétain was appointed vice premier. In June he asked for an armistice, upon which he was appointed 'chief of state', enjoying almost absolute powers. The armistice gave the Germans control over the north and west of France, including Paris, but left the remainder as a separate regime under Pétain, with its capital at Vichy. Officially neutral, in practice the regime collaborated closely with Germany, and brought in its own anti-Semitic legislation."

In December 1940, Pétain dismissed his vice-premier, Pierre Laval, for his policy of close Franco-German collaboration. But Laval's successors were unacceptable to the Germans and Laval was restored. In November 1942, in response to allied landings in North Africa, the Germans invaded the unoccupied zone of France. Vichy France remained nominally in existence, but Pétain became nothing more than a figurehead. In the summer of 1944, after the allied landings in France, Pétain was taken to Germany." [3]

Henri-Philippe Petain was tried and sentenced to death for collaborating with Germany on August 15, 1945, with the loss of all civil rights and confiscation of their property. However, the Court itself, given his advanced age, proposed to replace him the death penalty by the imprisonment.

General De Gaulle, head of the provisional Government, accepted the proposal that his death sentence to be commuted to life imprisonment and Pétain was transferred to the fortress of Portalet, located in the Pyrenees, to serve his sentence. Later, he was taken to Fort de Pierre Levée, on the Île d'Yeu off the Atlantic coast where Henri-Philippe Petain died on 23 July 1951.

[2] Background on meeting between Marshall Henri-Philippe Petain, General Weygand and Winston Churchill

"Paul Reynaud received us, firm and courteous despite the strain. We soon got down to discussion across the dining-room table; Petain, Reynaud, Weygand facing Churchill, Dill and me, with interpreters. General Georges joined us later. We talked for almost three hours, the discussion hardly advancing matters. The speakers were polite and correct, but although at that time the Maginot Line had not been attacked, it was soon evident that our French hosts had no hope.

Early in our talks, Weygand described the military situation, explaining how he had attempted to block a number of gaps in the line. He believed he had succeeded and, for the moment, the line held, but he had no more reserves. Somebody asked what would happen if another breach were made. 'No further military action will then be possible,' Weygand replied. Reynaud at once intervened sharply: 'That would be a political decision, Monsieur Ie General.' Weygand bowed and said: 'Certainly.' Georges told us that the French had altogether only some one hundred and ninety-five fighter aircraft left on the northern front.

Despite all the difficulties, our dinner, though simple, was admirably cooked and served. Reynaud presided, with Churchill on his right, Weygand sat opposite and I on his right. As we were taking our places, a tall and somewhat angular figure in uniform walked by on my side of the table. This was General Charles de Gaulle, Under-Secretary for Defence, whom I had met only once before. Weygand invited him pleasantly to take a place on his left. De Gaulle replied, curtly as I thought, that he had instructions to sit next to the British Prime Minister. Weygand flushed up, but made no comment, and so the meal began.

I had Marshal Petain on my other side. Conversation was not easy. His refrain was the destruction of France and the daily devastation of her cities, of which he mentioned several by name. I was sympathetic, but added that there were even worse fates than the destruction of cities. Petain rejoined that it was all very well for Britain to say that, we did not have the war in our country. When I said that we might have, I received an incredulous grunt in reply.

With General Weygand my talk was perfectly friendly and consisted mainly of a discussion about our available forces in Britain and what we were doing to speed their training. I had little cheer to give him. Weygand was something of an enigma. He had a famous reputation, crowned by his victory with Pilsudski over the Bolshevik forces in 1920. I had met him on several occasions, most recently early that year in the Middle East, and always found him friendly, quick and receptive, a modest man carrying his fame without affectation or conceit. He worked well with General Wavell, for the two men understood each other. I was glad when I heard that he had been called back to France to take over the supreme command. He achieved little, but probably no man could. At this stage, though always correct and courteous, he gave the impression of resigned fatalism. He was certainly not a man to fight the last desperate comer."

FYI COL Mikel J. Burroughs LTC Greg Henning MSgt Robert C Aldi CMSgt (Join to see) PVT Mark Zehner Lt Col Charlie Brown] SGT John " Mac " McConnell SP5 Mark Kuzinski PO1 H Gene Lawrence PO2 Kevin Parker PO3 Bob McCord LTC Jeff Shearer SGT Philip Roncari PO3 Phyllis Maynard CWO3 Dennis M. SFC William Farrell TSgt Joe C. SGT Carl Blas

(4)

(0)

LTC Stephen F.

FYI LTC Wayne Brandon LTC (Join to see) Lt Col John (Jack) Christensen Maj Bill Smith, Ph.D. Maj Robert Thornton CPT Scott Sharon SSG William Jones SSG Donald H "Don" Bates PO3 William Hetrick PO3 Lynn Spalding SPC Mark Huddleston SGT Rick Colburn CPL Dave Hoover SPC Margaret Higgins SSgt Brian Brakke SP5 Jeannie Carle Maj Marty Hogan SCPO Morris Ramsey Sgt Albert Castro

(2)

(0)

Read This Next

WWI

WWI WWII World War Two

WWII World War Two World History

World History Military History

Military History Treason

Treason